Coral LuLu curates intercultural spaces

Interviewer: Courtney Boag

Image: Feature photo by Uma Gu.

8 July, 2022

“I find anthropology to be an intriguing counterpart to the arts, especially methods of museum collections research, participant observation, and ethnography. As a curator, I long to understand other cultures, and through engaging in interdisciplinary and intercultural work, I think we can create more compelling art projects which explore the dialogue between cross cultures and their contributions to contemporary societies.”

Coral LuLu

Coral LuLu is an experienced curator, collaborator, artist and anthropology enthusiast. She has curated art exhibitions internationally in China, Mongolia, and the United States, as well as regionally in places such as Beijing, Jiangsu, Inner Mongolia and Tibet. Her most recent series of shows entitled Transcending Territories focuses on contemporary artists, influenced by traditionally nomadic Indigenous cultures of grassland, desert, and marine regions, including ethnic groups such as Mongolian, Tibetan, Sami, Navajo, Maasai, Bedouin, and Bajau. As part of building intercultural bridges, Coral sustains an active research program among diverse cultural communities, learning from local customs and adaptations to the natural environment as well as fostering friendships and collaborative partnerships worldwide.

Alongside her curatorial work, Coral maintains her own active studio practice in Songzhuang Art Village in east Beijing. Her work combines symbolic and natural materials along with more conventional multi-media to create temporary site-specific installations that bridge the natural and modern world. Her work is informed by a multidisciplinary approach, drawing from curatorial, artistic, anthropological and linguistic fields. I caught up with Coral to discuss her story in becoming an artist and curator, her work with nomadic cultures and why she feels anthropology creates important opportunities for intercultural work.

Coral, I understand you grew up in Cangzhou, Hebei Province in China, and that your family was a military family. What was life like for you growing up and how did you start practicing art and moving into the art curation world? Was it a challenging transition for you at all?

Yes, I was born in Cangzhou, Hebei Province. However, when I was two or three years old, I moved with my parents to a military base located near Inner Mongolia. It was a beautiful area located between a plateau and mountains, with woods, grasslands, and rivers nearby. I remember seeing so much nature all around me, with blue skies, white clouds, and low mountains. We could see sheep, cows, and horses eating freely in the mountains without any fences. As children we could go out to play in nature without adults watching – it was so much fun. At that time, my friends and I would run in the woodlands and collect different shaped stones in the shallow river, or sometimes I would ride horses borrowed from local herders with my father in the grasslands near the base.

My father and his colleagues sometimes went hunting, so we had wild animals such as roe deer, pheasant, boar, and hares for meals occasionally. Growing up, I gained familiarity with aspects of both farming and nomadic lifestyles, living close to nature, the soil, and plants. We had dogs, cats, chickens, and geese in our yard, and if I wanted a tomato or cucumber, my mum would pick it directly from the garden - you couldn’t imagine how fresh they were!

I feel that my generation was lucky since I was born and lived in times of peace. I have never lived through any war or disaster, even though I was in a military family at the same time that there were wars elsewhere in the world. To some extent, our families didn’t have to separate, and I grew up with the love of my family and could get a good education and a worldview that was full of empathy.

Eventually, I left for Inner Mongolia Normal University in Hohhot, the capital city of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. At university, I studied art and design, and it was there that I developed my aesthetic. After graduating, I became an intern for a documentary television department, interviewing artists and curators, gaining knowledge of the art field, and developing an interest in artist residencies, art gallery management, and curation. Eventually, I took a job in the art district as a gallery assistant, helping to organise exhibitions and participating in the business of art, and step by step, I worked my way up to becoming a curator. However, after ten years of running artist residencies and organising exhibitions, I became frustrated with the commercialisation of it all. I started to explore what I wanted to express as an individual and then launched an art project entitled Transcending Territories. Now I’m focused on contemporary art inspired by nomadic cultures. In working with contemporary artists from Mongolian and Tibetan cultures, and other nomadic indigenous backgrounds, I’ve come to realise the important impact that growing up in nature had on my own life.

Was curation was a challenging transition for me? I don’t think it was. In my life, the process of becoming a curator all came naturally. However, at this moment, I feel that I want more professional training to develop my approach and become a better curator, and for this reason, I’m planning on beginning my training in anthropology.

How do you hope anthropology will help you become a better curator?

As an art curator, besides having good taste in art selection, I should also have a broad cultural perspective, a strong theoretical system, and pluralistic knowledge. Anthropological research helps us to better understand different cultures and their similarities and differences. I want to focus on cultural anthropology and use the approaches of ethnography and ethnology to do deeper research and fieldwork, better understand the creations of nomadic artists, collect more meaningful resources, and bring this cultural information to our audiences around the world.

When I’m creating an exhibition, I visit people from nomadic backgrounds. I try to live with them in their community and visit their local festivals to get familiar with their lifestyles, customs, foods, games, ceremonies, and etiquette. At the same time, I try to visit artists and explore their backgrounds, and ask why they created these works, and what is the relationship between the artists and their culture. This is kind of my fieldwork. Then I select artists according to my curatorial concept, gathering them together to exhibit their artworks in physical or virtual spaces, and communicating our concepts through text, labels, talks, workshops, and publications. I think this comparative phase is kind of similar to ethnology.

Yes, I was born in Cangzhou, Hebei Province. However, when I was two or three years old, I moved with my parents to a military base located near Inner Mongolia. It was a beautiful area located between a plateau and mountains, with woods, grasslands, and rivers nearby. I remember seeing so much nature all around me, with blue skies, white clouds, and low mountains. We could see sheep, cows, and horses eating freely in the mountains without any fences. As children we could go out to play in nature without adults watching – it was so much fun. At that time, my friends and I would run in the woodlands and collect different shaped stones in the shallow river, or sometimes I would ride horses borrowed from local herders with my father in the grasslands near the base.

My father and his colleagues sometimes went hunting, so we had wild animals such as roe deer, pheasant, boar, and hares for meals occasionally. Growing up, I gained familiarity with aspects of both farming and nomadic lifestyles, living close to nature, the soil, and plants. We had dogs, cats, chickens, and geese in our yard, and if I wanted a tomato or cucumber, my mum would pick it directly from the garden - you couldn’t imagine how fresh they were!

I feel that my generation was lucky since I was born and lived in times of peace. I have never lived through any war or disaster, even though I was in a military family at the same time that there were wars elsewhere in the world. To some extent, our families didn’t have to separate, and I grew up with the love of my family and could get a good education and a worldview that was full of empathy.

Eventually, I left for Inner Mongolia Normal University in Hohhot, the capital city of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. At university, I studied art and design, and it was there that I developed my aesthetic. After graduating, I became an intern for a documentary television department, interviewing artists and curators, gaining knowledge of the art field, and developing an interest in artist residencies, art gallery management, and curation. Eventually, I took a job in the art district as a gallery assistant, helping to organise exhibitions and participating in the business of art, and step by step, I worked my way up to becoming a curator. However, after ten years of running artist residencies and organising exhibitions, I became frustrated with the commercialisation of it all. I started to explore what I wanted to express as an individual and then launched an art project entitled Transcending Territories. Now I’m focused on contemporary art inspired by nomadic cultures. In working with contemporary artists from Mongolian and Tibetan cultures, and other nomadic indigenous backgrounds, I’ve come to realise the important impact that growing up in nature had on my own life.

Was curation was a challenging transition for me? I don’t think it was. In my life, the process of becoming a curator all came naturally. However, at this moment, I feel that I want more professional training to develop my approach and become a better curator, and for this reason, I’m planning on beginning my training in anthropology.

How do you hope anthropology will help you become a better curator?

As an art curator, besides having good taste in art selection, I should also have a broad cultural perspective, a strong theoretical system, and pluralistic knowledge. Anthropological research helps us to better understand different cultures and their similarities and differences. I want to focus on cultural anthropology and use the approaches of ethnography and ethnology to do deeper research and fieldwork, better understand the creations of nomadic artists, collect more meaningful resources, and bring this cultural information to our audiences around the world.

When I’m creating an exhibition, I visit people from nomadic backgrounds. I try to live with them in their community and visit their local festivals to get familiar with their lifestyles, customs, foods, games, ceremonies, and etiquette. At the same time, I try to visit artists and explore their backgrounds, and ask why they created these works, and what is the relationship between the artists and their culture. This is kind of my fieldwork. Then I select artists according to my curatorial concept, gathering them together to exhibit their artworks in physical or virtual spaces, and communicating our concepts through text, labels, talks, workshops, and publications. I think this comparative phase is kind of similar to ethnology.

So please tell me about your artist practice today, what are you inspired by and what messages do you hope to communicate through your work?

As an artist, I draw on perspectives from years of working with indigenous collaborators. I use symbolic materials such as popcorn (like sudden blossoms) and potatoes (rhizomatic growth), combined with conventional media and found objects to create temporary site-specific installations exploring the energy from nature and expressing a personal vision of harmonious integration with the natural world. I employ naturally occurring elements in improvisational installations seeking balanced relations with the natural world. While I will usually have a basic idea of my goals for a new project beforehand, I do work spontaneously and respond to the site and environment where I am. I want to be curious and open to the process; you cannot control it but must be available to follow your feelings and intuition.

In the future, I will continue my projects in a series of temporary works about metaphoric and symbolic transformations. I activate the symbolic resonance and energy of specific materials in dialogue with environments; for example, the use of adobe in indigenous housing traditions interests me because it is a resource that comes directly from a landscape, and produces an efficient home that is cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter. I would like to have connections with the materials and environments in places where I work and take inspiration from the communities and local plants and creatures. At the same time, I also have many other projects planned. I’m working on a program to promote indigenous languages and I’m also thinking of producing a documentary about Life after Secularisation, which would explore the experiences of Buddhist monks as they return to their normal lives after leaving temples.

These projects sound incredible Coral. Now, you’ve travelled extensively around the world teaching art to so many people through several charity initiatives that you’ve developed, can you tell me about some of these programs?

I have travelled extensively around the world, but mostly to do research for my own curatorial work. My charity work has largely occurred in China so far, through work with artist residency participants. Before Covid-19, my residency program accepted a couple of international artists per year. We suggested that all residency participants contribute their time and knowledge to our local community, so I organised art workshops with the artists for local disabled children. We have held different kinds of art workshops with local kids and their families, such as music, sculpture, drawing, and silk screen printing workshops. Since we need to pay attention to all family members, each time we only accept a maximum of ten kids and their families. As time has gone on, more local artists have joined us also. Our charity group had grown quite a bit before the pandemic put a stop to such gatherings. Nevertheless, it has been a fantastic experience for all our participants.

In your role as an art curator, you’ve just touched on the point that you are now working on a lot of collaborations with emerging artists from nomadic regions around the world, what inspired you to work primarily with nomadic artists?

Emerging artists from nomadic regions and cultural backgrounds are very intelligent and creative but have fewer opportunities to show their work in public. I want to use my connections and knowledge to help them to go beyond their local communities and have more chances to be involved in the wider art world.

After organising my first Transcending Territories exhibition, I embarked on a personal journey to explore indigenous arts around the world. I began in the West Bank to learn more about the nomadic Bedouin peoples of the desert, before flying to Buenos Aires for a half-month residency with the Argentine art organisation, Panal 361.

In Buenos Aires, I met veteran tango singer Hector Raul Osses who introduced me to his native Mapuche community, a South American Indian tribe. Then Argentine artist, Laura Otego (a 2014 participant in my artist residency) introduced me to a photographer named Ronnie Keegan, who had been working with the Romani people in Argentina. Then, while I was in Finland for the 2018 ResArtis annual conference, I met with some of the nomadic Sami people of Northern Europe. These experiences were like informal fieldwork for me. These encounters help me to learn more about nomadism around the world, which has become the central theme of my work. From then, I have come to believe in the magic of cultural commonalities and exchange that can transcend political divisions, cross borders, and forge connections.

From Asia and Europe to the Americas, the commonalities and particularities of nomadic peoples fascinate me. Over the millennia, diverse nomadic peoples around the world have developed highly sophisticated cultural perspectives rooted in their knowledge of regional landscapes and experience of nature. The ways of thinking that emerge from traditionally nomadic cultures comprise what I call “nomadism”, which is more than merely a lifestyle of mobility. Nomadism is a discourse of philosophy, aesthetics, and relations with nature that remains long-term, sustainable, and relevant to contemporary society. Nomadism is dynamic and flexible, comprising living traditions that continue to change and adapt to the contemporary global world. In some places, nomadic lifestyles are still an active way of life, while in others, the descendants of nomadic cultures live in urban and sedentary contexts but still maintain insights gained through generations of nomadic coexistence with nature. I believe nomadism can be a dynamic force in the modern world and may spawn new ways of living in this globalised society and cyberspace, restructuring these spaces in ways that are more humane and connected to nature. Nomadic cultures value ecological balance to protect water, natural resources, and the environment. For example, Mongolian herders want the land to be useful in the future. So, they move their animals in the winter to warmer places, giving grasslands time to rest, while the feet of the moving animals refresh the land like people receiving a relaxing massage. Normally nomadic peoples move twice a year between summer and winter grasslands.

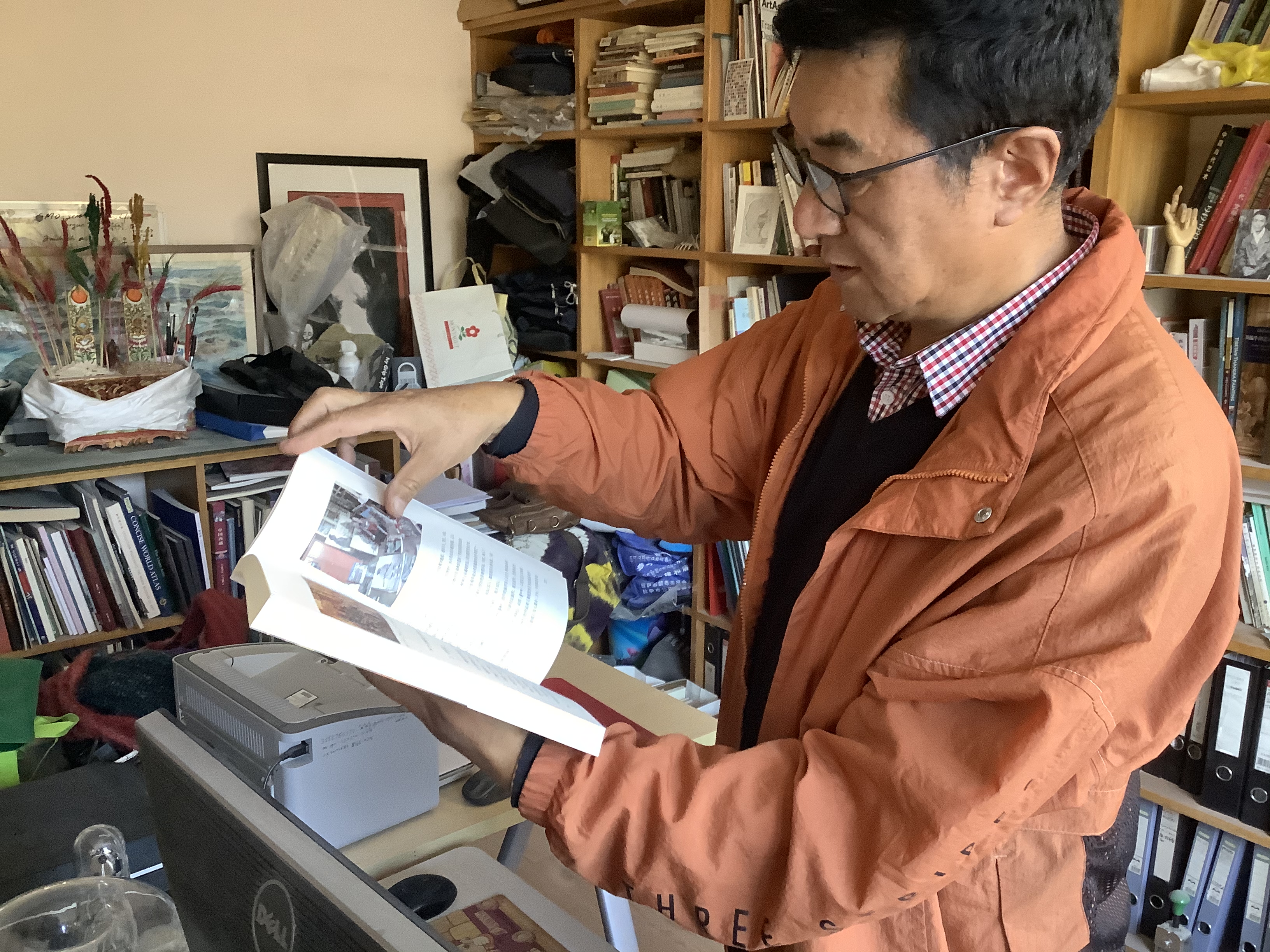

Coral visiting Inner Mongolian artist Quan Bao in his Beijing studio, 2021. Photo by Coral LuLu.

Coral visiting Tibetan artist Tsewang Tashi in his studio Lhasa in 2020 (photo by Coral LuLu).

Tashi is a very important Tibetan artist and scholar, and has just published a book entitled ‘A History of Art in the Twenty Century Tibet in 2020’.

Tashi is a very important Tibetan artist and scholar, and has just published a book entitled ‘A History of Art in the Twenty Century Tibet in 2020’.

So let’s talk a bit more about your exhibition Transcending Territories. You curated this project in 2017 with your co-curator Dalkh-Ochir Yondonjunai who is the director of the Mongolian Contemporary Art Centre. In this exhibition, you brought together many artists from Mongolia to showcase their work for the first time. Then in 2018, you reprised the exhibition again in Lhasa and brought together artists from both Mongolia and Tibet. Can you tell me a bit about this exhibition?

Transcending Territories is an ongoing series of contemporary art exhibitions focusing on artists from nomadic cultural backgrounds and perspectives. It started in Autumn of 2015, when an art institution in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia called Art Mongolia and began planning an exhibition to promote Mongolian artists in Beijing China. I was selected to work as a curator and after a year of research, I suggested touring exhibitions of Mongolian ethnic artists from China, Mongolia, and Russia, as well as others inspired by Mongolian cultures. We had not expected my suggestions to be met with vehement opposition when we asked the Mongolian embassy in China for support. The reasons were probably political, but we never knew why it was so sensitive. Without sponsorship, Art Mongolia had to give up the project. Since I had visited many artists over those two years, including Mongolian artists in China and Mongolia, as well as Mongolian artists in the United States, I could not bear to leave the project unfinished. So I mobilised all the resources I could, and after two years of preparation, my exhibit Transcending Territories 2017 (co-curated with Mr. Dalkh-Ochir Yondonjunai) successfully opened in Art Tai Space in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. This was a thematic show focusing on the profound impact of Mongolian culture on the world.

My curation explores ideas of harmonious relations among human beings, animals, and nature through nomadism and contemporary art. I want exhibitions that challenge people to better understand nomadic peoples and the values of nomadism, seeking better ecological harmony. As my vision has developed, my exhibition plans have expanded from the initial focus on Mongolian and Tibetan cultures to contemporary art exhibits including nomadic peoples of the world and global artists influenced by nomadic cultures.

I chose the theme of Transcending Territories as an exhibition series exploring the interrelated concepts of “Region-Nomadism-Contemporary World”. This led to Transcending Territories 2018 at the Scorching Sun Lab, in Lhasa, Tibet (co-curated with Dr. Uranchimeg Tsultem from Indiana University) which presented the first exhibition dialogue between contemporary art influenced by Mongolian and Tibetan cultures. The following year, I organised Transcending Territories 2019 for the Red Ger Art Gallery in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, but the show was cancelled due to the gallery’s unexpected temporary closing. The Covid pandemic has prevented further exhibitions, but I expect it to continue in the coming years.

Looking back, I’m proud of my persistence in following the inspiration of nomadism and my belief in its importance to contemporary society. Working with collaborators, I will continue exploring relationships among individuals, traditions, and contemporary life. I see art as a way to work together to oppose global consumerism, amplify the voices of disadvantaged people, and oppose environmental destruction. I want to be a part of developing systems of change for all sentient beings to reconnect with the natural world in creative new ways.

The opening of Transcending Territories 2017, Art Tai Space, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. Gallery manger, Chen Yan gives a welcome speech and acknowledges the first exhibition of international artists inspired by Mongolian culture coming together in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. Photo by Yu Gaofeng (China) & Wan Shu (China).

The opening performance

Artist: Enkhbold Togmidshiirev (Mongolia)

Title: To the origin

Material: Performance and installation

Year: 2017

Photo by Yu Gaofeng (China) & Wan Shu (China)

Artist: Enkhbold Togmidshiirev (Mongolia)

Title: To the origin

Material: Performance and installation

Year: 2017

Photo by Yu Gaofeng (China) & Wan Shu (China)

The pictures below were taken from Transcending Territories 2017. Participating artists included (not in order): Enkhbold Togmidshiirev (Mongolia), Erdenebayar Monkhor (Mongolia), Munguntsetseg Lkhagvasuren (Mongolia), Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav (Mongolia), Michel Haillard (France), Li Bo (Inner Mongolia, China), Qin Ga (Inner Mongolia, China), Quan Bao (Inner Mongolia, China), Ikhajav (Inner Mongolia, China), Urgen (Inner Mongolia, China), Shinetana (Inner Mongolia, China) and Wang Zhengping (Inner Mongolia, China). Photo by Yu Gaofeng (China) & Wan Shu (China).

More recently, you’ve turned to your own studio practice and are now working out of a space in the Songzhuang Art Village in Beijing where thousands of other artists also work. How has the experience been working alongside so many other artists?

Songzhuang Art Village is located east of Beijing. There are 6,000-8,000 artists who live and work there, including writers, painters, sculptors, musicians, photographers, film directors, curators, and dancers. It is an international community, with artists from around the world. It is very convenient for artists because we can easily buy art supplies, participate in exhibitions, find professional shipping transportation, meet dealers, and join the artist community here. We visit each other to discuss literature, art, philosophy, or even politics and economics. We often share opportunities; if a curator is looking for artists, we share this information. The village brings in international resources for artists and curators who live and work there, and I met artists whom I now work with through the art village community. Through communicating with the artists in the Village, we find inspiration from each other and we learn from each other’s knowledge and experiences.

Ok, so I’m really excited about one of your most recent projects entitled ‘Learning Mother Language is Our Right’ which focuses on revitalising indigenous languages. What inspired you to begin this project and what do you hope to communicate through this work?

Learning Mother Language is Our Right comes out of my studio practice projects. During my travels, I have found a growing number of people cannot speak, nor write, their mother tongue; the language or dialect belonging to the cultural heritage or ethnic group that a person subjectively identifies with. This is a widespread phenomenon from Asia to the Americas.

According to the United Nation, there are around 3,000 languages in danger, especially among indigenous and ethnic minority languages. Languages become endangered when the number of speakers declines through death or shifts to more dominant languages. The preservation and vitality of linguistic diversity is a global problem. These mother tongues preserve cultural knowledge and histories that can never be fully translated and are vital for the survival of cultures and fostering diversity around the world. So the diversity of mother tongues, the diversity of cultures, the diversity of species, and the diversity of habitats are all closely related. It is crucial to value, encourage, and teach mother languages to retain the richness of cultural diversity and knowledge, as well as affirm Indigenous and minority identities while counteracting the detrimental effects of discrimination.

As Audrey Azoulay (Director-General of UNESCO) says, “Every language has a certain rhythm, a certain way of approaching things, of thinking about them. Learning or forgetting a language is thus not merely about acquiring or losing a means of communication. It is about seeing an entire world either appear or fade away”.

Learning Mother Language is Our Right is still underway and we are asking for Indigenous and ethnic minority friends from around the world to participate in affirming the global revitalisation of mother tongue languages. I hope to produce a crowd-sourced photographic installation showing support for the crucial importance of global linguistic diversity.

The opening of Transcending Territories 2018, The Scorching Sun Art Lab, Lhasa, Tibet. List of part participants (from left to right): Somani (Tibet, China), Tsewang Tashi (Tibet, China), Li Bo (Inner Mongolia, China), Ikhajav (Inner Mongolia, China), Qin Ga | Chyanga (Inner Mongolia, China), Gade (Tibet, China), Shinetana (Inner Mongolia, China), Pen Pa (Tibet, China), Tsering Nyandak (Tibet, China), Coral LuLu (Inner Mongolia, China), Wusuronggui (Inner Mongolia, China), Nortse (Tibet, China), Quan Bao (Inner Mongolia, China). Photo by Damdul.

Artist: Munguntsetseg Lkhagvasuren (Mongolia)

Title: Steppe vase

Material: Horse hair, pot with tea, wood, fabrics and cups

Year: 2016

From Transcending Territories 2018

![]()

Artist: Pen Pa (Tibet, China)

Title: I will move up the mountain

Material: Conceptual video

Photographer: Jiang Woo and Tashi Norpu

Year: 2014

From Transcending Territories 2018

Title: Steppe vase

Material: Horse hair, pot with tea, wood, fabrics and cups

Year: 2016

From Transcending Territories 2018

Artist: Pen Pa (Tibet, China)

Title: I will move up the mountain

Material: Conceptual video

Photographer: Jiang Woo and Tashi Norpu

Year: 2014

From Transcending Territories 2018

Artist: Gade (Tibet, China)

Title: Serve the People

Material: Buddha beads, black yakwool and copper coin.

Year: 2018

From Transcending Territories 2018

Title: Serve the People

Material: Buddha beads, black yakwool and copper coin.

Year: 2018

From Transcending Territories 2018

A question I like to ask everyone is, what role do you think art and anthropology have in building a better global society?

My curatorial goals are closely tied to gaining experience in anthropology to better interpret artists and their work. I find anthropology to be an intriguing counterpart to the arts, especially methods of museum collections research, participant observation, and ethnography. As a curator, I long to understand other cultures, and through engaging in interdisciplinary and intercultural work, I think we can create more compelling art projects which explore the dialogue between cross cultures and their contributions to contemporary societies.

Anthropology touches upon many different issues that we are confronted with today and plays an important and indispensable role in building a better global society. As human beings from different ethnic groups, nations, and regions, we need to better understand other cultures. I see anthropology as being useful for learning more about different cultures, but it also helps us to develop more tolerant attitudes and empathy to reduce prejudice. It allows one to learn by immersion in a cultural group as an “insider”, and to view one's own cultural group as an "outsider". We also need to think more ecologically; a way of thinking which is not humanist or anthropocentric, but which conceives of ourselves as being a part of the world and nature, belonging equally within natural dynamics.

Coral visiting Tibetan artist Tsering Dolma’s studio in Lhasa, Tibet, China in 2020 (photo by Tsewang Tashi).

There are few women artists in Tibet. Tsering’s work is inspired by breath and ideas of reincarnation.

Interested to learn more about Coral’s work? Follow her page here.

Learn more about the exhibition that Coral curated by visiting Transcending Territories.

To view the artist profiles for Transcending Territories.

To be involved in Coral’s latest project, visit Learning Mother Language is Our Right.

Follow Coral via @corallubaby

Learn more about the exhibition that Coral curated by visiting Transcending Territories.

To view the artist profiles for Transcending Territories.

To be involved in Coral’s latest project, visit Learning Mother Language is Our Right.

Follow Coral via @corallubaby