David Boarder Giles uncovers value in dumpsters

Interviewer: Courtney Boag

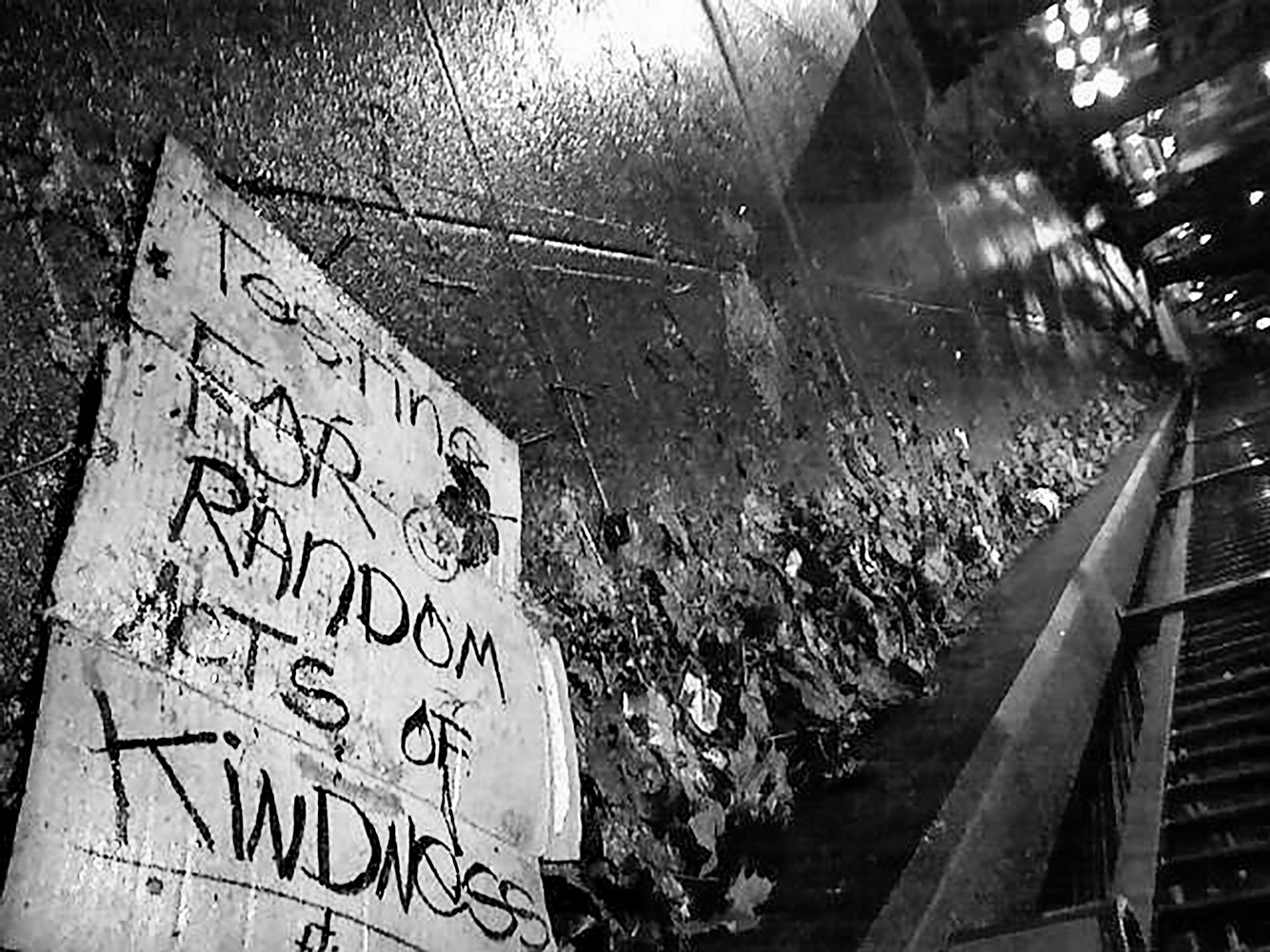

Images: David Boarder Giles

27 March, 2022

“commercial waste is about manufacturing scarcity. If hungry people and edible food are separated by a dumpster, that’s a social relationship, a taboo or prohibition, that’s been created by capitalism to maintain the sanctity of our consumer economy.”

David Boarder Giles

David Boarder Giles is a Lecturer in Anthropology at Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia. His research engages with economic anthropology, environmental anthropology, urban ethnography and political anthropology to explore fundamental issues such as waste, sprawling cities, alternative economies and homelessness.

David’s research has been instrumental in shedding light on how food waste plagues so many urban environments across the world today and why our current perceptions of value need to change if we are to address global issues of food insecurity and homelessness. Evidently, these are significant issues for our time that require our attention before - what had been made very clear to us during the pandemic, becomes washed away down our ‘collective memory hole.’

David’s research has been instrumental in shedding light on how food waste plagues so many urban environments across the world today and why our current perceptions of value need to change if we are to address global issues of food insecurity and homelessness. Evidently, these are significant issues for our time that require our attention before - what had been made very clear to us during the pandemic, becomes washed away down our ‘collective memory hole.’

Firstly, I’d love to know how you got into anthropology? What’s your personal story there?

I think I’ve been an anthropologist since I was ten, if not younger. When I was very small, my family life already demanded, for various reasons, that I pay close attention to the people around me, to try to empathise and understand what they were thinking and how they made sense of the world.

And then when I was ten, my mother remarried and moved to the United States. So I was thrown into a brand new cultural context. I suddenly had a really powerful sense of being an outsider. People—both children and adults—would ask my why I had an accent, and I would tell them that to me, they had the accent. Some of them just couldn’t accept that. So I had a quick lesson about ethnocentrism. And I remember having to learn very quickly, like an ethnographer, how Americans spoke and thought, so that I could communicate with them. My impressions at the time were that they believed God wanted them to own guns and they were extremely racist. I’m glad to say I learned to see the country with much more nuance as I got older, although my ten-year-old instincts were not totally wrong. And I made up at that point not to fit in, not to trust an idea just because it seems like “common sense” to a lot of people, and to look for to the cultural blindspots of the people around me.

In other words, I learned early on to try to think like an anthropologist!

And then when I was in my late teens, and just starting university, I met a lot of homeless people in my neighbourhood who were pandhandling and asking for food. I was already the sort of person who felt both curious and heartbroken to meet people in such awful circumstances, so I spent a lot of time talking with them, and sharing food, and learning about their lives. I realised that there are structures in a society that distribute wealth, power, and privilege unequally. I later learned words for these structures, like “structural violence” and “racial capitalism.”

So by the time I took my first anthropology class, I was already looking for some way to build a life around these sorts of interests and passions. Originally, I thought I might be a photojournalist, but anthropology taught me that you can spend longer covering a story inn much more depth, and challenge your own assumptions about it in the process.

So David, could you tell me a little bit about what your current research explores?

Lately, I’ve been trying to document what has happened to unsheltered people during the last two years, as a result of the pandemic. It’s a collaborative project with researchers in several cities, called “Shelter in the Pandemic City”, tracking developments on the ground in four cities: Melbourne, Seattle, San Francisco, and Buenos Aires.

The crisis was a lightning rod for a lot of contradictory forces—somehow for better and for worse at exactly the same time. Like a lot of researchers, I saw it exacerbating and amplifying issues that I had already been studying. I was already worried about the ways in which homelessness has become a linked, global phenomenon. Cities across the world have been affected by tidal shifts in the global economy over the last three or four decades that not only widen the inequalities between white collar and blue collar classes, but turn real estate into a “hypercommodity” or even a kind of “global currency” for the super wealthy, as Peter Marcuse and David Madden put it. The result is that many “global” metropolises have seen related explosions in cost of living, displacement, and homelessness.

These are all questions of value, which is at the heart of all my work. How do we value life, and how does that translate into economic value or disposability? In the global city, both people and things are often treated like they’re disposable.

My first book, A Mass Conspiracy to Feed People: Food Not Bombs and the world-class waste of global cities, had tried to document the effects of some of those parallels when it came to public space, and the sorts of restrictions that criminalise homelessness and food sharing—laws which segregate these displaced populations from the public sphere as much as possible. With the pandemic, in essence, we saw such criminalisation taken to the nth degree, as lockdown rendered homelessness effectively illegal in some places, and some unsheltered individuals racked up thousands of dollars in fines, because they didn’t have anywhere else to go.

But on the other hand, the pandemic also revealed those inequalities and made them untenable. It created—for a very brief moment—a window of political opportunity to house many of those people in hotels, and supplement welfare supports. It was far, far from perfect. And it was done in an ad hoc way, for arguably less than humanitarian reasons. But it nonetheless established a precedent for a right to shelter and a right to basic income. That came, however, at the expense of our right to the city. So at the moment, I’m trying to record experiences of that period, and the political and social possibilities it held—before they disappear down the collective memory hole!

I think I’ve been an anthropologist since I was ten, if not younger. When I was very small, my family life already demanded, for various reasons, that I pay close attention to the people around me, to try to empathise and understand what they were thinking and how they made sense of the world.

And then when I was ten, my mother remarried and moved to the United States. So I was thrown into a brand new cultural context. I suddenly had a really powerful sense of being an outsider. People—both children and adults—would ask my why I had an accent, and I would tell them that to me, they had the accent. Some of them just couldn’t accept that. So I had a quick lesson about ethnocentrism. And I remember having to learn very quickly, like an ethnographer, how Americans spoke and thought, so that I could communicate with them. My impressions at the time were that they believed God wanted them to own guns and they were extremely racist. I’m glad to say I learned to see the country with much more nuance as I got older, although my ten-year-old instincts were not totally wrong. And I made up at that point not to fit in, not to trust an idea just because it seems like “common sense” to a lot of people, and to look for to the cultural blindspots of the people around me.

In other words, I learned early on to try to think like an anthropologist!

And then when I was in my late teens, and just starting university, I met a lot of homeless people in my neighbourhood who were pandhandling and asking for food. I was already the sort of person who felt both curious and heartbroken to meet people in such awful circumstances, so I spent a lot of time talking with them, and sharing food, and learning about their lives. I realised that there are structures in a society that distribute wealth, power, and privilege unequally. I later learned words for these structures, like “structural violence” and “racial capitalism.”

So by the time I took my first anthropology class, I was already looking for some way to build a life around these sorts of interests and passions. Originally, I thought I might be a photojournalist, but anthropology taught me that you can spend longer covering a story inn much more depth, and challenge your own assumptions about it in the process.

So David, could you tell me a little bit about what your current research explores?

Lately, I’ve been trying to document what has happened to unsheltered people during the last two years, as a result of the pandemic. It’s a collaborative project with researchers in several cities, called “Shelter in the Pandemic City”, tracking developments on the ground in four cities: Melbourne, Seattle, San Francisco, and Buenos Aires.

The crisis was a lightning rod for a lot of contradictory forces—somehow for better and for worse at exactly the same time. Like a lot of researchers, I saw it exacerbating and amplifying issues that I had already been studying. I was already worried about the ways in which homelessness has become a linked, global phenomenon. Cities across the world have been affected by tidal shifts in the global economy over the last three or four decades that not only widen the inequalities between white collar and blue collar classes, but turn real estate into a “hypercommodity” or even a kind of “global currency” for the super wealthy, as Peter Marcuse and David Madden put it. The result is that many “global” metropolises have seen related explosions in cost of living, displacement, and homelessness.

These are all questions of value, which is at the heart of all my work. How do we value life, and how does that translate into economic value or disposability? In the global city, both people and things are often treated like they’re disposable.

My first book, A Mass Conspiracy to Feed People: Food Not Bombs and the world-class waste of global cities, had tried to document the effects of some of those parallels when it came to public space, and the sorts of restrictions that criminalise homelessness and food sharing—laws which segregate these displaced populations from the public sphere as much as possible. With the pandemic, in essence, we saw such criminalisation taken to the nth degree, as lockdown rendered homelessness effectively illegal in some places, and some unsheltered individuals racked up thousands of dollars in fines, because they didn’t have anywhere else to go.

But on the other hand, the pandemic also revealed those inequalities and made them untenable. It created—for a very brief moment—a window of political opportunity to house many of those people in hotels, and supplement welfare supports. It was far, far from perfect. And it was done in an ad hoc way, for arguably less than humanitarian reasons. But it nonetheless established a precedent for a right to shelter and a right to basic income. That came, however, at the expense of our right to the city. So at the moment, I’m trying to record experiences of that period, and the political and social possibilities it held—before they disappear down the collective memory hole!

What is dumpster diving and how can anthropology contribute to the study of dumpster diving and waste?

Dumpster diving is exactly what it sounds like. Digging through dumpsters and bins to recover valuable things that have been thrown away. I did quite a bit of it for my first project! Contrary to many “commonsense” assumptions, it’s neither unsafe nor gross if you know what you’re doing. In fact, it turns out we throw away enormous quantities of valuable goods. Including a lot of edible food. (It takes a bit of experience to recognise what’s valuable, and which bins will be worth exploring, though. Don’t just run out and dig out some rotten avocadoes and tell everyone I said it was fine!)

The dumpsters I was most interested in were commercial dumpsters, because their waste tell us something about capitalism. If for-profit retailers generate such massive surpluses, then it suggests that capitalism isn’t the efficient distributor of resources that it is often claimed to be. It must work according to some more complex logic. And if those excesses are thrown away while at the same time hunger and food insecurity grows, then the “law” of supply and demand starts to seems incredibly arbitrary. Something else must be at work.

So, whereas some social scientists might apply models like supply and demand, and try to fine tune their efficiency and precision, an anthropologist knows to think beyond essentialist models, and look closely at what’s being thrown away. We need to ask what kinds of cultural values and social relationships are being reproduced here.

And in the same way that homelessness tells us something about our values—and who a society treats as disposable—dumpster diving can teach us a great deal about the values that animate our economies. In particular, what I’ve argued is that commercial waste is about manufacturing scarcity. If hungry people and edible food are separated by a dumpster, that’s a social relationship, a taboo or prohibition, that’s been created by capitalism to maintain the sanctity of our consumer economy. (And, incidentally, the same thing is true of housing: there are more vacant properties than there are people experiencing homelessness, in many cities, including Melbourne, where I live.)

The history of value is an interesting one, but what strikes me about the nature of ‘value’ is its ambiguity. So, I wanted to ask you, how and why do we attach value to certain objects while devaluing other objects?

That’s a great question! The short answer is that it reflects whose desires and whose labour are respected or afforded more power and importance.

But the long answer is more interesting… Whereas some social scientists treat value as something that’s universally defined in a single way (take the “law” of supply and demand, for example), anthropologists treat value as a social construction that’s specific to a given society or community. So what’s valuable to one community might be disposable to another, and vice versa. (And, of course, the people who exercise power in any given society have more influence over that.) To make it more complex, the word “value” can refer to wealth, cultural importance, or linguistics (as in the “value of the signifier”). And these all influence one another.

But what’s often true is that value is fungible. In other words, it’s exchangeable or translatable. Because any society is actually a diverse, complex constellation of stakeholders and situations, no single value can ever be all encompassing. Not only do things have different kinds of value —the use value of things (or what can be done with them) is often very different from their exchange value (what they can be traded for)—but different people value them differently in different contexts.

So some anthropologists have suggested that “value” reflects what happens when we develop shared rituals and platforms for reconciling all the different ways that people, places, and things are esteemed, desired, or afforded importance in a society. In Australian society, for example, we have lots of these sorts of ritual spaces, from art galleries to underground music scenes to stock markets, which channel those diverse forces into a common language. Incidentally, the dumpster is a similar kind of ritual space—except a negative one. It devalues things, rather than values them. Regardless of whether something is useful or edible, once a thing ends up in the dumpster, it becomes for most intents and purposes worthless. (Although that doesn’t stop some companies from prosecuting people for “stealing” their trash.)

Of course, under capitalism, the dominant ritual space for reckoning value is called a “market,” and the common, fungible language for translating value is capital or currency. But economic anthropologists know that this lingua franca isn’t absolute. It’s a reflection of all the social and political relationships that make up capitalism, and it is only as good as our shared belief in it. For that reason, Marx called it a “social hieroglyphic.”

Does anthropology have a role in critiquing this larger economic system and breaking down assumptions of how we should all be participating in the economy?

Absolutely. Anthropology’s job, as Ruth Benedict is supposed to have said, is to “make the world safe for human difference.” Part of what that means is to value other societies’ ideas and practices for their own sake, rather than looking for an “ideal” form. And so as a discipline, anthropology simply cannot take for granted anysociety’s norms, let alone the dominant ones.

If the dominant economy were a gift economy or a society where all property was held in common, well then maybe our job would be to demonstrate the logic of a market economy and private property. But since we live under capitalism, where free markets and private profits are the dominant force, it’s our job to show that it has not always been so, and that other kinds of economies continue to exist.

Not only that, but our job is both to make the “strange familiar” and to make the “familiar strange”—in this case, to notice things about our own economy and our own systems of value in places like Australia that remain either cultural blindspots, or that pass for common sense. (I always tell my students that “common sense” is rarely as common or as inherently sensible as we’ve been taught.) That’s one of the reasons I study waste and homelessness. After all, how could it be sensible to keep up an economy that throws away food while people go hungry, and that keeps properties vacant when people are homeless?

I understand you also run a podcast called ‘Conversations in Anthropology’ with some of your colleagues at Deakin. What is this podcast about and why should people listen in?

Our podcast is one of my favourite parts of my job! We’ve been running it for about five years now. At first, it was a whim—I said to my colleague, Tim, who was co-organising our regular anthropology seminar series at Deakin—why don’t we get our guests to have a little chat with us beforehand, and we can pop it up on the web? But we both quickly realised how important it could be to create new kinds of genres and intellectual spaces where we could talk about our work as anthropologists. And as we’ve gone on, we’ve invited a team of like-spirited scholars to collaborate on it. We have a really lovely little podcast family, now!

I’ve always believed that anthropology shouldn’t be bottled up in universities, and that there are lots of “anthropologists” out there who just haven’t found the language for it yet—like me in my teens. Also, there weren’t as many anthropology podcasts back then. So we wanted to create a space where different kinds of people might come into contact with anthropology. I also loved the podcast On Being, and I loved that there was an audience out there who were excited to take a deep dive into a single thinker’s ideas, so I wanted to do that with anthropology too. And as time has gone on, I’ve realised that it’s a really special kind of genre. We read our guests’ work closely, talk about it broadly, and celebrate it—which is usually something that only happens when somebody retires, dies, or wins an award. So it has come to feel like a gift, and a way to pay forward a spirit of intellectual generosity which hopefully benefits us all.

And they’re really lovely, fascinating conversations, too. On one hand, we have time to dwell on complex ideas in depth, rather than boiling them down to a soundbyte. And on the other hand, it’s a really, holistic, humane sort of conversation. Your whole self—the whole human being—is welcome, from the precision and rigour of your academic work to your silliest or most personal insights. It’s truly anthropological in that sense. So it’s unlike an academic seminar or lecture—which can be not only formal, but also, let’s be honest, quite uptight spaces where some people in the audience are there to pick apart your ideas.

What do you hope people can take away from your research?

Above all, two things. First of all, a sense of possibility. Anthropology can teach us that however things are, they haven’t always been so. (And they still aren’t, in many places.) In fact, while Progress-with-a-Capital-P is a kind of cultural myth, change is one of the only cultural constants. That brings me some peace.

And second, what the best anthropology does is to give people new tools to notice what’s going on in the society they live in. The kinds of subjects I’ve focussed on—homelessness and waste—often hide in plain sight. And if we don’t see them, then we’re missing something important about the way our society is structured. So I hope I can contribute to making them visible, and in the process help people connect the dots in order to better see those larger structures.

Absolutely. Anthropology’s job, as Ruth Benedict is supposed to have said, is to “make the world safe for human difference.” Part of what that means is to value other societies’ ideas and practices for their own sake, rather than looking for an “ideal” form. And so as a discipline, anthropology simply cannot take for granted anysociety’s norms, let alone the dominant ones.

If the dominant economy were a gift economy or a society where all property was held in common, well then maybe our job would be to demonstrate the logic of a market economy and private property. But since we live under capitalism, where free markets and private profits are the dominant force, it’s our job to show that it has not always been so, and that other kinds of economies continue to exist.

Not only that, but our job is both to make the “strange familiar” and to make the “familiar strange”—in this case, to notice things about our own economy and our own systems of value in places like Australia that remain either cultural blindspots, or that pass for common sense. (I always tell my students that “common sense” is rarely as common or as inherently sensible as we’ve been taught.) That’s one of the reasons I study waste and homelessness. After all, how could it be sensible to keep up an economy that throws away food while people go hungry, and that keeps properties vacant when people are homeless?

I understand you also run a podcast called ‘Conversations in Anthropology’ with some of your colleagues at Deakin. What is this podcast about and why should people listen in?

Our podcast is one of my favourite parts of my job! We’ve been running it for about five years now. At first, it was a whim—I said to my colleague, Tim, who was co-organising our regular anthropology seminar series at Deakin—why don’t we get our guests to have a little chat with us beforehand, and we can pop it up on the web? But we both quickly realised how important it could be to create new kinds of genres and intellectual spaces where we could talk about our work as anthropologists. And as we’ve gone on, we’ve invited a team of like-spirited scholars to collaborate on it. We have a really lovely little podcast family, now!

I’ve always believed that anthropology shouldn’t be bottled up in universities, and that there are lots of “anthropologists” out there who just haven’t found the language for it yet—like me in my teens. Also, there weren’t as many anthropology podcasts back then. So we wanted to create a space where different kinds of people might come into contact with anthropology. I also loved the podcast On Being, and I loved that there was an audience out there who were excited to take a deep dive into a single thinker’s ideas, so I wanted to do that with anthropology too. And as time has gone on, I’ve realised that it’s a really special kind of genre. We read our guests’ work closely, talk about it broadly, and celebrate it—which is usually something that only happens when somebody retires, dies, or wins an award. So it has come to feel like a gift, and a way to pay forward a spirit of intellectual generosity which hopefully benefits us all.

And they’re really lovely, fascinating conversations, too. On one hand, we have time to dwell on complex ideas in depth, rather than boiling them down to a soundbyte. And on the other hand, it’s a really, holistic, humane sort of conversation. Your whole self—the whole human being—is welcome, from the precision and rigour of your academic work to your silliest or most personal insights. It’s truly anthropological in that sense. So it’s unlike an academic seminar or lecture—which can be not only formal, but also, let’s be honest, quite uptight spaces where some people in the audience are there to pick apart your ideas.

What do you hope people can take away from your research?

Above all, two things. First of all, a sense of possibility. Anthropology can teach us that however things are, they haven’t always been so. (And they still aren’t, in many places.) In fact, while Progress-with-a-Capital-P is a kind of cultural myth, change is one of the only cultural constants. That brings me some peace.

And second, what the best anthropology does is to give people new tools to notice what’s going on in the society they live in. The kinds of subjects I’ve focussed on—homelessness and waste—often hide in plain sight. And if we don’t see them, then we’re missing something important about the way our society is structured. So I hope I can contribute to making them visible, and in the process help people connect the dots in order to better see those larger structures.

Interested to learn more about David’s research? Visit his academic portfolio and read his journal articles here.

Get your copy of David’s latest book Mass Conspiracy to Feed People: Food Not Bombs and the world-class waste of global cities here.

Check out the Conversations in Anthropology podcast here.

Get your copy of David’s latest book Mass Conspiracy to Feed People: Food Not Bombs and the world-class waste of global cities here.

Check out the Conversations in Anthropology podcast here.