Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this interview may contain images and names of deceased persons.

︎︎︎

David Trigger reflects on 40 years as an Australian anthropologist

Interviewer: Courtney Boag

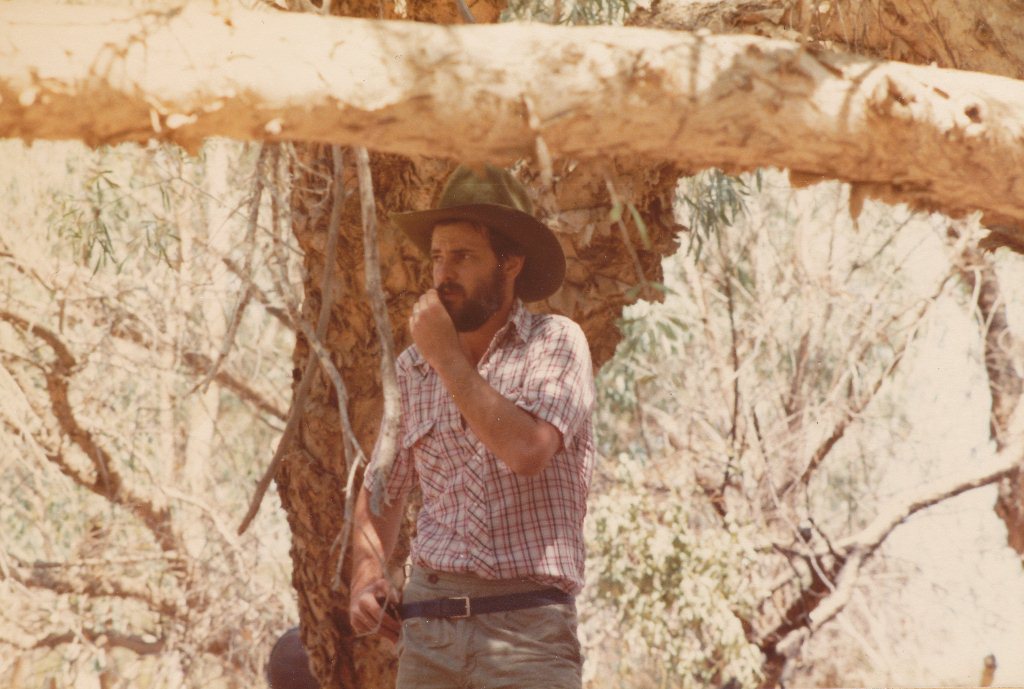

Image:

David at the Nicholson River land claim hearing, Northern Territory, 1982 (Photo: Robert Blowes)

12 October, 2022

“Anthropology can draw attention to cultural difference, in the broader context of structural societal constraints and opportunities, in ways that are distinctive among other social science and humanities disciplines. While there are many potential pitfalls through the process of cross-cultural translation and related forms of analysis, there is also a promise of contributing to an understanding of a kind much needed in today’s world”

David Trigger

Over the past four

decades, Australian Anthropologist and Emeritus Professor David Trigger has

been contributing to the discipline of anthropology in diverse and meaningful

ways . Growing up in a

working family in the suburban city of Brisbane during the 1950’s and 60’s,

David became interested in understanding culture, society and history partly

through reflecting on his own positionality as a young Jewish boy who was

preparing himself for his bar mitzvah. David explains how visiting

his family’s rabbi and learning to sing in Hebrew “honed his ear[s] to the

sounds of another language” and “reinforced the sense of an identity peripheral

to the lives” of his suburban school friends. This early interest in

understanding cultural and social identities motivated David to write an

honours thesis on his own multifaceted identity and, in his own words, became a

“huge learning experience” in his “early stage of becoming a social

scientist”.

A few years later, at the age of 24, David was given the opportunity to work as a site recorder in the Gulf of Carpentaria in north west Queensland. The remote Aboriginal community of Doomadgee became the base for David’s studies. Like many towns across Australia, Doomadgee became a location for the establishment of a Christian Mission during the early 1930’s. However, for many years, access to non-Indigenous people was tightly controlled by the non-Aboriginal mission managers. When David began working in the region during the early 1970’s, there were more than 50 non-Indigenous workers and around 900 Aboriginal residents at Doomadgee. The history of pastoralism in the region had also given rise to a mix of ancestries including Aboriginal, European and Asian. This culturally diverse environment inspired David to understand how everyday life is experienced for those who were living with this intercultural boundary in the ‘Gulf country’. This area of interest became the topic of his PhD thesis and would go on to inform much of his life’s work.

David’s formative years working in remote communities within Australia and forming relationships with diverse cultural identities has seen him explore complex questions around senses of belonging in post-colonial societies. Particularly, David has been instrumental in speaking to the overlaps and divergences of identity and feelings of belonging that are experienced by those with Aboriginal, Euro-Australian and Asian ancestries within post-colonial Australia. He has also drawn from concepts of ‘nativeness’ and ‘invasiveness’, as they are understood in the context of nature and society, to understand what their implications are for the formation and maintenance of cultural identities, and for environmental and land management. Additionally, David has contributed significantly to the anthropological study of Indigenous systems of land tenure in his applied research on resource development negotiations and in his role as an expert witness in native title claim work across the country.

I’ve admired David’s work for many years now and was honoured to speak with him about his early experiences in becoming an anthropologist and to reflect on his long-standing career, which has equally spanned both the academic and applied fields. I was also eager to hear his thoughts on where the discipline of anthropology is headed including the opportunities and challenges that may lie ahead.

A few years later, at the age of 24, David was given the opportunity to work as a site recorder in the Gulf of Carpentaria in north west Queensland. The remote Aboriginal community of Doomadgee became the base for David’s studies. Like many towns across Australia, Doomadgee became a location for the establishment of a Christian Mission during the early 1930’s. However, for many years, access to non-Indigenous people was tightly controlled by the non-Aboriginal mission managers. When David began working in the region during the early 1970’s, there were more than 50 non-Indigenous workers and around 900 Aboriginal residents at Doomadgee. The history of pastoralism in the region had also given rise to a mix of ancestries including Aboriginal, European and Asian. This culturally diverse environment inspired David to understand how everyday life is experienced for those who were living with this intercultural boundary in the ‘Gulf country’. This area of interest became the topic of his PhD thesis and would go on to inform much of his life’s work.

David’s formative years working in remote communities within Australia and forming relationships with diverse cultural identities has seen him explore complex questions around senses of belonging in post-colonial societies. Particularly, David has been instrumental in speaking to the overlaps and divergences of identity and feelings of belonging that are experienced by those with Aboriginal, Euro-Australian and Asian ancestries within post-colonial Australia. He has also drawn from concepts of ‘nativeness’ and ‘invasiveness’, as they are understood in the context of nature and society, to understand what their implications are for the formation and maintenance of cultural identities, and for environmental and land management. Additionally, David has contributed significantly to the anthropological study of Indigenous systems of land tenure in his applied research on resource development negotiations and in his role as an expert witness in native title claim work across the country.

I’ve admired David’s work for many years now and was honoured to speak with him about his early experiences in becoming an anthropologist and to reflect on his long-standing career, which has equally spanned both the academic and applied fields. I was also eager to hear his thoughts on where the discipline of anthropology is headed including the opportunities and challenges that may lie ahead.

David, I wanted to begin by asking you how you came into anthropology? Were you always interested in studying cultures and society?

I initially tried a cadetship in a big building firm studying two nights a week at, what was then, the Queensland Institute of Technology. I was beginning training as a building estimator along with architecture and quantity surveying students. Straight out of high school, I had grown up in a family where my father was a small building contractor, and probably like so many young people, I just went with the flow of expectations. I had enjoyed a high school subject named ‘geographical drawing and perspective’ and thought being part of building construction would be good.

However, after one year, it turned out I lost interest and decided to go to university. This was a world I had no knowledge of, but I was attracted by the topics about society, culture and history. So, anthropology and sociology courses, along with philosophy, gradually became my trajectory. During some holiday periods away from study at the university, I worked as a surveyor’s ‘chainman’, or assistant, which gave me skills in spatially mapping locations. I managed one stint for six weeks in north Queensland which was a learning experience far from the theories of the classroom about regional society and race relations.

I think there is much to reflect on as to why people are attracted to the humanities and social sciences and why I differed from several mates I knew who stayed the course to become a draftsman, an architect or a quantity surveyor. One interesting issue debated is whether growing up with a sense of being different from peers may contribute to being engaged by subjects addressing culture and society. While it is important to recognise that many young people have private lives that engender quite diverse senses of difference, one aspect for me may have been my upbringing in a small Jewish community in Brisbane.

I certainly felt different among friends and neighbours when aged 12, I responded to the family’s expectation to visit the home of a rabbi to study one afternoon each week over the course of some nine months to prepare for having a bar mitzvah. Learning to sing in Hebrew, and then perform publicly in the synagogue on the day, honed my ear to the sounds of another language. It also reinforced the sense of an identity peripheral to the lives of my suburban school friends, although this was alongside my comfortable everyday participation in the life of a largely working-class city suburb through the 1950s and 1960s.

I wrote about Jewish identity in Brisbane for an honours thesis that included audio recorded interviews with young people I had known through childhood and adolescence. Writing that thesis, and reflecting on my own multifaceted identity, was a huge learning experience at an early stage of becoming a social scientist.

Do you think it has been important for you to reflect on your own story throughout your career as an anthropologist?

I find it enormously informative and engaging when anthropologists reflect on their personal lives in the context of their work and career. I can’t agree if colleagues suggest, as I have noticed happening at times, that there is little of analytical interest in their own social and cultural backgrounds. Among scholars, teachers and applied research practitioners working on settler society issues, I notice what I think is an unfortunate assumption that diminishing the societal and cultural significance of their own ancestries and family circumstances is constitutive of a commitment to Aboriginal people, including those who have become participants in their research.

At least, there is a tendency among some anthropologists to express ambiguity as to the political legitimacy of their own family and cultural inheritances, given the historical legacies of living in a post-settler society. This to me suggests a broader current malaise among those articulating what is intended as a politically progressive position on Indigeneity and Australian identity. In my view, whether this is politically progressive or counter-productive, both intellectually and in terms of practical outcomes, needs greater and more honest discussion.

The positionality of the scholar and its implications for what anthropologists do has of course been a topic of much writing and debate over the past few decades. Without trying to address the complexities here, it is worth noting the risk of a politicised self-deprecation among colleagues working in Indigenous Australia. I support exploration of the positive, as well as the negative, aspects of non-Indigenous cultural inheritances. I find it unproductive, awkward, and possibly ingenuous, if empathy for senses of legitimate belonging and connections to place in the researcher’s own life is positioned as unfashionable.

At its most extreme, the suggestion can be that too little dismissal of settler and migrant belonging is somehow tone deaf to political commitment to assertions of Indigenous identity. Yet an assumption that the anthropologist’s belonging and legitimacy in Australia’s post-settler society is politically unprogressive is a dead end, both for our intellectual understanding of the realities of a post-settler world, and in terms of useful practical engagements across Indigenous Australia.

This is really interesting David and I want to return to this topic a little later on, but before we jump into that discussion, I wanted to ask about your PhD thesis, entitled ‘Doomadgee: a study of power relations and social action in a north Australian Aboriginal settlement’ which explored social life at the Doomadgee Aboriginal settlement in the Gulf of Carpentaria. What inspired you to focus your research on this settlement and what were you hoping to communicate through this work?

This research started when I took up an exciting opportunity at the age of 24. After 18 months as a very young assistant lecturer at the Darwin Community College in the Northern Territory, I managed to get a job as a site recorder that was funded by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. A few of my mentors at the University of Queensland received the grant and advertised the position. At the time, most anthropological research in Queensland was done on the Cape York Peninsula; however, this job was rather located in the huge region labelled ‘the Gulf Country’.

I was given a Toyota land cruiser, various fieldwork equipment and was largely left to work out how to do the job on my own. While I initially spent time at various places from Mt Isa to Camooweal, Burketown to Mornington Island and across the Northern Territory border to the Robinson River Station and Borroloola, it was Doomadgee in the far northwest corner of Queensland that became the base for my studies. Doomadgee had an Indigenous population of close to 900 people in the late 1970s and had never had substantial anthropological research done there.

It was not an easy setting to access for research as, for many years, the Mission management had tightly controlled access and residence by outsiders. There were more than 50 Whitefellas living and working at Doomadgee, and I became engaged with understanding everyday life across the intercultural boundary. I was lucky enough to have a job recording sites of cultural significance, involving bush trips, while simultaneously doing ethnographic fieldwork on race relations which eventually became the topic of my PhD thesis.

Given the history of pastoralism from the 1860s, the mix of ancestries from Aboriginal, European and Asian forebears, and the administrative authority of a fundamentalist Brethren Church, the setting was incredibly rich with the legacies of colonialism. I completed the PhD study over a period of some five years. Doubtless as with other anthropologists in that era, the work and everyday experiences of close living with Indigenous families became greatly influential in both my professional and personal life.

As to what I wanted to communicate through the work, the thesis emerged as my attempt to portray a history of inter-racial and intercultural relations, as well as the continuities and changes in the cultural lives of Aboriginal people. The circumstances of the Whitefellas who were both missionaries and professional staff including teachers, nurses and tradespeople were included in my interviews and participant observation. I focused on everyday aspects of social interaction across life domains that remained separate yet structurally connected. Authoritarian ethnocentrism among Whitefellas coexisted with benevolent paternalism. Historical studies enabled understanding of the practical benefits of the Mission in light of racism and exclusion often central to the patterns of life on the cattle stations and in small towns.

I developed long-term connections with some Indigenous families, much more so than any subsequent social relationships with the Whitefellas. With hindsight, I realised much later in my career that I could have tried harder to engage with the senses of place and belonging of Whitefellas on the cattle stations although my closeness to what was happening in the Indigenous domain necessarily limited fieldwork interactions with station people.

I initially tried a cadetship in a big building firm studying two nights a week at, what was then, the Queensland Institute of Technology. I was beginning training as a building estimator along with architecture and quantity surveying students. Straight out of high school, I had grown up in a family where my father was a small building contractor, and probably like so many young people, I just went with the flow of expectations. I had enjoyed a high school subject named ‘geographical drawing and perspective’ and thought being part of building construction would be good.

However, after one year, it turned out I lost interest and decided to go to university. This was a world I had no knowledge of, but I was attracted by the topics about society, culture and history. So, anthropology and sociology courses, along with philosophy, gradually became my trajectory. During some holiday periods away from study at the university, I worked as a surveyor’s ‘chainman’, or assistant, which gave me skills in spatially mapping locations. I managed one stint for six weeks in north Queensland which was a learning experience far from the theories of the classroom about regional society and race relations.

I think there is much to reflect on as to why people are attracted to the humanities and social sciences and why I differed from several mates I knew who stayed the course to become a draftsman, an architect or a quantity surveyor. One interesting issue debated is whether growing up with a sense of being different from peers may contribute to being engaged by subjects addressing culture and society. While it is important to recognise that many young people have private lives that engender quite diverse senses of difference, one aspect for me may have been my upbringing in a small Jewish community in Brisbane.

I certainly felt different among friends and neighbours when aged 12, I responded to the family’s expectation to visit the home of a rabbi to study one afternoon each week over the course of some nine months to prepare for having a bar mitzvah. Learning to sing in Hebrew, and then perform publicly in the synagogue on the day, honed my ear to the sounds of another language. It also reinforced the sense of an identity peripheral to the lives of my suburban school friends, although this was alongside my comfortable everyday participation in the life of a largely working-class city suburb through the 1950s and 1960s.

I wrote about Jewish identity in Brisbane for an honours thesis that included audio recorded interviews with young people I had known through childhood and adolescence. Writing that thesis, and reflecting on my own multifaceted identity, was a huge learning experience at an early stage of becoming a social scientist.

Do you think it has been important for you to reflect on your own story throughout your career as an anthropologist?

I find it enormously informative and engaging when anthropologists reflect on their personal lives in the context of their work and career. I can’t agree if colleagues suggest, as I have noticed happening at times, that there is little of analytical interest in their own social and cultural backgrounds. Among scholars, teachers and applied research practitioners working on settler society issues, I notice what I think is an unfortunate assumption that diminishing the societal and cultural significance of their own ancestries and family circumstances is constitutive of a commitment to Aboriginal people, including those who have become participants in their research.

At least, there is a tendency among some anthropologists to express ambiguity as to the political legitimacy of their own family and cultural inheritances, given the historical legacies of living in a post-settler society. This to me suggests a broader current malaise among those articulating what is intended as a politically progressive position on Indigeneity and Australian identity. In my view, whether this is politically progressive or counter-productive, both intellectually and in terms of practical outcomes, needs greater and more honest discussion.

The positionality of the scholar and its implications for what anthropologists do has of course been a topic of much writing and debate over the past few decades. Without trying to address the complexities here, it is worth noting the risk of a politicised self-deprecation among colleagues working in Indigenous Australia. I support exploration of the positive, as well as the negative, aspects of non-Indigenous cultural inheritances. I find it unproductive, awkward, and possibly ingenuous, if empathy for senses of legitimate belonging and connections to place in the researcher’s own life is positioned as unfashionable.

At its most extreme, the suggestion can be that too little dismissal of settler and migrant belonging is somehow tone deaf to political commitment to assertions of Indigenous identity. Yet an assumption that the anthropologist’s belonging and legitimacy in Australia’s post-settler society is politically unprogressive is a dead end, both for our intellectual understanding of the realities of a post-settler world, and in terms of useful practical engagements across Indigenous Australia.

This is really interesting David and I want to return to this topic a little later on, but before we jump into that discussion, I wanted to ask about your PhD thesis, entitled ‘Doomadgee: a study of power relations and social action in a north Australian Aboriginal settlement’ which explored social life at the Doomadgee Aboriginal settlement in the Gulf of Carpentaria. What inspired you to focus your research on this settlement and what were you hoping to communicate through this work?

This research started when I took up an exciting opportunity at the age of 24. After 18 months as a very young assistant lecturer at the Darwin Community College in the Northern Territory, I managed to get a job as a site recorder that was funded by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. A few of my mentors at the University of Queensland received the grant and advertised the position. At the time, most anthropological research in Queensland was done on the Cape York Peninsula; however, this job was rather located in the huge region labelled ‘the Gulf Country’.

I was given a Toyota land cruiser, various fieldwork equipment and was largely left to work out how to do the job on my own. While I initially spent time at various places from Mt Isa to Camooweal, Burketown to Mornington Island and across the Northern Territory border to the Robinson River Station and Borroloola, it was Doomadgee in the far northwest corner of Queensland that became the base for my studies. Doomadgee had an Indigenous population of close to 900 people in the late 1970s and had never had substantial anthropological research done there.

It was not an easy setting to access for research as, for many years, the Mission management had tightly controlled access and residence by outsiders. There were more than 50 Whitefellas living and working at Doomadgee, and I became engaged with understanding everyday life across the intercultural boundary. I was lucky enough to have a job recording sites of cultural significance, involving bush trips, while simultaneously doing ethnographic fieldwork on race relations which eventually became the topic of my PhD thesis.

Given the history of pastoralism from the 1860s, the mix of ancestries from Aboriginal, European and Asian forebears, and the administrative authority of a fundamentalist Brethren Church, the setting was incredibly rich with the legacies of colonialism. I completed the PhD study over a period of some five years. Doubtless as with other anthropologists in that era, the work and everyday experiences of close living with Indigenous families became greatly influential in both my professional and personal life.

As to what I wanted to communicate through the work, the thesis emerged as my attempt to portray a history of inter-racial and intercultural relations, as well as the continuities and changes in the cultural lives of Aboriginal people. The circumstances of the Whitefellas who were both missionaries and professional staff including teachers, nurses and tradespeople were included in my interviews and participant observation. I focused on everyday aspects of social interaction across life domains that remained separate yet structurally connected. Authoritarian ethnocentrism among Whitefellas coexisted with benevolent paternalism. Historical studies enabled understanding of the practical benefits of the Mission in light of racism and exclusion often central to the patterns of life on the cattle stations and in small towns.

I developed long-term connections with some Indigenous families, much more so than any subsequent social relationships with the Whitefellas. With hindsight, I realised much later in my career that I could have tried harder to engage with the senses of place and belonging of Whitefellas on the cattle stations although my closeness to what was happening in the Indigenous domain necessarily limited fieldwork interactions with station people.

Site visits with the judge, claimants and government parties for the

Robinson River Garawa land claim,1988

(Photo: David Mardiros)

(Photo: David Mardiros)

David at the Nicholson River land claim hearing, Northern Territory, 1982 (Photo: Robert Blowes)

You’ve continued working in the Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia since your doctorate research in the late 1970s and have gone on to explore a whole range of issues including the impacts of mining in remote Australia, the politics of belonging in a post-colonial society, race relations and cultural change. However, before diving into these elements of your work, I wanted to ask you about your early, and ongoing, involvement in native title. I understand that Aboriginal land rights became a significant priority in Australia during the 1970s, so was it a natural progression for you to move into this applied anthropology work after your doctorate?

It was ‘natural’ I guess just in that it seemed to me a no-brainer when asked by Aboriginal land councils to prepare reports for land claims. How was it useful or ethically preferable to say no? It was less relevant to building an academic career though it also was relatively well remunerated. But I was never so ensconced in the lure of producing journal articles and other academic publications that I would walk away from opportunities to work on outcomes linked to achievement of legal rights for the Aboriginal people with whom I had been working. The work, furthermore, and contrary to arguments from some anthropology colleagues, was incredibly interesting intellectually. I learned much from legal colleagues about supporting research findings with articulated ethnographic data and they learned much from me about the difficulties of cross-cultural translation of landed identities to the requirements of evidence in legal procedures.

Initially, there were a couple of big land claims in the lower Gulf Country in the Northern Territory west from Doomadgee. Those were in the 1980s when many anthropologists were invited, requested and engaged formally to do that difficult, yet often personally rewarding, work. The Northern Territory Land Rights Act was seen as a great hope among Aboriginal people making the claims, as well as a broad network of Whitefellas, who were employed across a host of roles as part of the operation of the legislation. There was the promise of getting real negotiating rights in land as well as the powerful symbolic significance of the legal system of Australia taking seriously Indigenous cultural relationships to country.

Some of the history of anthropologists collaborating with lawyers and other professionals, while working closely with Indigenous Traditional Owners, has been written about. However, there is more to recount about the professional and personal investments among anthropologists, and others of goodwill, who laboured to produce outcomes from the Northern Territory legislation.

Connected with the land claims in the Northern Territory were cultural heritage surveys in Queensland across the lower Gulf Country where I had been recording sites and mapping cultural landscapes. Proponents of new projects, particularly mining exploration, were funding studies as part of the development of their economic initiatives. The fieldwork for such heritage work was, and has largely remained, short term and highly focused on practical outcomes. The work went through various stages of different approaches. Documenting details of cultural connections to country was not always what was needed, so the methodology became ‘clearing’ specific site locations, e.g. drill holes, as either without constraints from the perspective of traditional law or sensitive because of spiritual and related properties of the land. Nevertheless, any conviction that cultural heritage work is a simple task of recording ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers from Traditional Custodians is flawed – a longer story probably best left for another conversation.

When, in the early 1990s, the Mabo case happened and the Commonwealth Native Title Act was passed, the kind of work anthropologists had been doing for some 15 years in the Northern Territory expanded across the entire continent. There has been plenty of criticism of native title, but my approach has continued to respond to requests and engagements to work on claims and a wide range of related issues. I don’t agree with the proposition that applied research of this kind is ethically inappropriate for anthropologists. I also have found it, over many years, to be intellectually stimulating, as well as productive of practical beneficial outcomes, in the Gulf Country and elsewhere.

The Gulf country is a multi-cultural environment which is home to the Indigenous Waanyi, Gangalidda and Garrwa people, as well as the descendants of many European and Chinese settlers, as you have mentioned. How have these various groups negotiated rights to land in the region since the introduction of native title?

In my opinion, native title has hugely improved the bargaining position of Indigenous groups. It has also provided a new vehicle for post-colonial politics both within the Indigenous domain and across intercultural relations where aspirations for Indigenous rights have been pursued. Native title has not created Indigenous politics of dispute, as anybody who carried out research prior to Mabo knows. Yes, native title has introduced a new vehicle for disputation and tensions, but it has hardly created intra-Indigenous contests over rights to land and waters.

Native title has not proved to be any kind of great solution to the myriad issues facing a country that has inherited a relatively recent colonial past. For those like me who regard economic development to address poverty and youth hopelessness as the bedrock of finding such solutions, native title is certainly only a partial success, and much more so in some parts of the continent than others. Nevertheless, when the symbolic value of recognition of traditional connections to country is combined with the settings where economic improvements on the ground have occurred, the value of anthropological work in native title is clear.

Anthropologists have been, in some ways, at the centre of native title issues despite the process being run by lawyers and the courts. I say that because it is anthropologists, among some others, who are asked to address and help explain Indigenous evidence to judges, lawyers and government public servants. The literature and research orientations of anthropology has also necessarily influenced industry people who otherwise just want to get on with their particular visions for viable economic developments.

Anthropologists complicate things when they are required to address such aspects of native title as the complexities of changing oral traditions connected with cultural landscapes, recuperation and re-inscription of cultural meanings on the land, diverse approaches to what we can term the ‘politics of indigenism’, and much more. It is both a highly stimulating and potentially frustrating setting in which to work as an anthropologist.

It was ‘natural’ I guess just in that it seemed to me a no-brainer when asked by Aboriginal land councils to prepare reports for land claims. How was it useful or ethically preferable to say no? It was less relevant to building an academic career though it also was relatively well remunerated. But I was never so ensconced in the lure of producing journal articles and other academic publications that I would walk away from opportunities to work on outcomes linked to achievement of legal rights for the Aboriginal people with whom I had been working. The work, furthermore, and contrary to arguments from some anthropology colleagues, was incredibly interesting intellectually. I learned much from legal colleagues about supporting research findings with articulated ethnographic data and they learned much from me about the difficulties of cross-cultural translation of landed identities to the requirements of evidence in legal procedures.

Initially, there were a couple of big land claims in the lower Gulf Country in the Northern Territory west from Doomadgee. Those were in the 1980s when many anthropologists were invited, requested and engaged formally to do that difficult, yet often personally rewarding, work. The Northern Territory Land Rights Act was seen as a great hope among Aboriginal people making the claims, as well as a broad network of Whitefellas, who were employed across a host of roles as part of the operation of the legislation. There was the promise of getting real negotiating rights in land as well as the powerful symbolic significance of the legal system of Australia taking seriously Indigenous cultural relationships to country.

Some of the history of anthropologists collaborating with lawyers and other professionals, while working closely with Indigenous Traditional Owners, has been written about. However, there is more to recount about the professional and personal investments among anthropologists, and others of goodwill, who laboured to produce outcomes from the Northern Territory legislation.

Connected with the land claims in the Northern Territory were cultural heritage surveys in Queensland across the lower Gulf Country where I had been recording sites and mapping cultural landscapes. Proponents of new projects, particularly mining exploration, were funding studies as part of the development of their economic initiatives. The fieldwork for such heritage work was, and has largely remained, short term and highly focused on practical outcomes. The work went through various stages of different approaches. Documenting details of cultural connections to country was not always what was needed, so the methodology became ‘clearing’ specific site locations, e.g. drill holes, as either without constraints from the perspective of traditional law or sensitive because of spiritual and related properties of the land. Nevertheless, any conviction that cultural heritage work is a simple task of recording ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers from Traditional Custodians is flawed – a longer story probably best left for another conversation.

When, in the early 1990s, the Mabo case happened and the Commonwealth Native Title Act was passed, the kind of work anthropologists had been doing for some 15 years in the Northern Territory expanded across the entire continent. There has been plenty of criticism of native title, but my approach has continued to respond to requests and engagements to work on claims and a wide range of related issues. I don’t agree with the proposition that applied research of this kind is ethically inappropriate for anthropologists. I also have found it, over many years, to be intellectually stimulating, as well as productive of practical beneficial outcomes, in the Gulf Country and elsewhere.

The Gulf country is a multi-cultural environment which is home to the Indigenous Waanyi, Gangalidda and Garrwa people, as well as the descendants of many European and Chinese settlers, as you have mentioned. How have these various groups negotiated rights to land in the region since the introduction of native title?

In my opinion, native title has hugely improved the bargaining position of Indigenous groups. It has also provided a new vehicle for post-colonial politics both within the Indigenous domain and across intercultural relations where aspirations for Indigenous rights have been pursued. Native title has not created Indigenous politics of dispute, as anybody who carried out research prior to Mabo knows. Yes, native title has introduced a new vehicle for disputation and tensions, but it has hardly created intra-Indigenous contests over rights to land and waters.

Native title has not proved to be any kind of great solution to the myriad issues facing a country that has inherited a relatively recent colonial past. For those like me who regard economic development to address poverty and youth hopelessness as the bedrock of finding such solutions, native title is certainly only a partial success, and much more so in some parts of the continent than others. Nevertheless, when the symbolic value of recognition of traditional connections to country is combined with the settings where economic improvements on the ground have occurred, the value of anthropological work in native title is clear.

Anthropologists have been, in some ways, at the centre of native title issues despite the process being run by lawyers and the courts. I say that because it is anthropologists, among some others, who are asked to address and help explain Indigenous evidence to judges, lawyers and government public servants. The literature and research orientations of anthropology has also necessarily influenced industry people who otherwise just want to get on with their particular visions for viable economic developments.

Anthropologists complicate things when they are required to address such aspects of native title as the complexities of changing oral traditions connected with cultural landscapes, recuperation and re-inscription of cultural meanings on the land, diverse approaches to what we can term the ‘politics of indigenism’, and much more. It is both a highly stimulating and potentially frustrating setting in which to work as an anthropologist.

David, with from left: Grace Pamtoonda, anthropologist Myrna Tonkinson, Gladys Goodman,

Louie Mick, Limmerick Peter, Hannah Barclay, unknown, at the Nicholson River land claim hearing, Northern Territory, 1982

(Photo: Robert Blowes)

In my experience, it is obvious that mining can potentially be a positive or negative opportunity for Aboriginal individuals, families and wider communities. This is also the case for the broader population of citizens, including those who make a living from the work opportunities of the industry. Mining is hardly categorically, or in some total sense, either good or bad. Along with its centrality in producing commodities essential for Australian lifestyles, it is also a fascinating social field for research. Its engagements with Aboriginal people are one aspect of mining operations that are an important arena of the Australian economy and society.

There is much written and said about mining as being incommensurate with Indigenous cultural landscapes. And, indeed, there are cases where large open cut mines are inconsistent with, or contrary, to spiritual significance across land and waters. For the aspect of Aboriginal cultural traditions that stresses non-change of the land as an ideal, there is no doubt that the physical disturbance of mining projects, albeit usually in a relatively confined area of square kilometres, is regarded as an unattractive option in Indigenous relationships with country.

However, the caveat to that issue, is firstly that complete non-change to country is not necessarily fundamental to all Indigenous views. Secondly, that Aboriginal people just like everybody else will, at times, trade off the less than desirable mining project for vitally needed economic opportunities. If anthropologists, along with others, ignore the enormous need for young Indigenous people to achieve meaningful work and financial circumstances beyond poverty, that is hardly a politically progressive approach. This is to point to the risk of essentialising culture and spiritual significance of country while ignoring the urgent realities of both physical and mental health crises associated with disaffection and boredom among young people.

David, you’ve been influential in progressing literature around concepts of ‘nativeness’ in Australia and the politics of belonging in a post-colonial society. You’ve spoken a little on how you’ve come to these issues, but I’d love to dive into this a little more with you. Can you describe what you’ve aimed to contribute to these wider discussions, which are not only relevant to the Australian environment, but are highly applicable across the globe?

After years of mapping Indigenous cultural landscapes, my thinking turned to consider senses of place across the wider Australian society. As I suggested earlier, while this is not a topic that may be fashionable for researchers wanting to empathise with the discreteness of Indigenous cultural traditions, it is my view that the kinds of belonging developed among the descendants of settlers and migrants is intellectually engaging and potentially politically productive given the necessities and realities of cross-cultural coexistence.

As I indicated earlier, I have not been convinced that support for Indigenous senses of place and belonging requires or rests on a diminishment or ignoring of what develops over time for the broad diverse citizenry of a post-settler society. The generalised category of a ‘non-Indigenous’ cultural identity in Australia is vague when portrayed as a trope without the obvious qualification that it masks enormous social, cultural and economic diversity across the nation.

That issue has led me over the last 15 or so years to research projects on environmentalism and its implications for Australian senses of place, alongside the national significance of development ideology. One engaging window on to that matter is the debates about native flora and fauna in relation to what has been historically ‘introduced’. I have found that issue productive and informative as to changing Australian assumptions and approaches to the question of the increasing identification of persons with what is understood to be an ‘indigenous’ aspect of their ancestry.

It would seem there will be more and more people who are phenotypically ‘white’, particularly in southeast Australia, who will aspire to assert that they are more ‘native’ than those without an Indigenous forebear. This is an enormously rich field of study for anthropology and my approach is to address complex and diverse ideas of ‘nativeness’ in the history and present of the post-settler society.

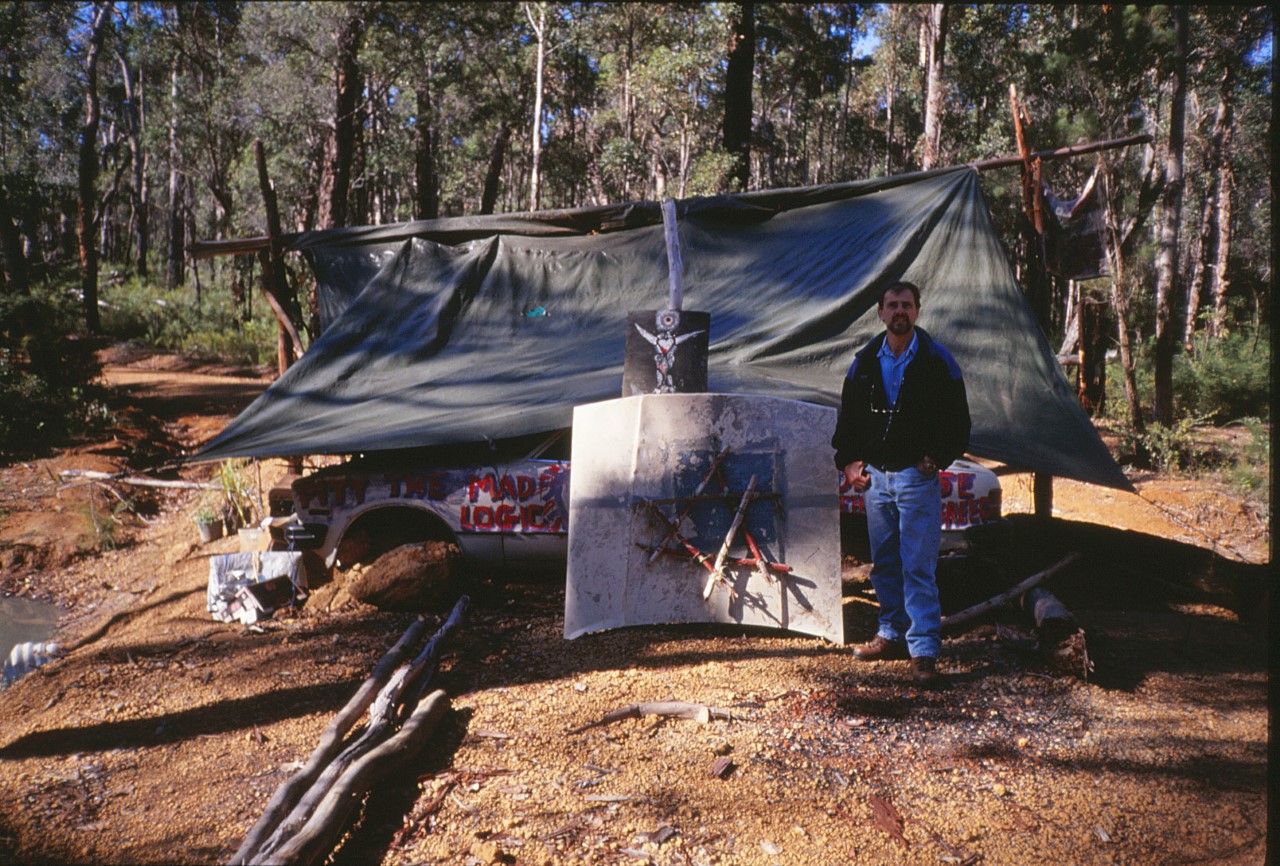

Forest protest camp, 'Platypus', southwest Australia, 1999 (Photo: Adele Millard)

Discussing stone tool artefacts previously relocated by Century Mine. Boojamulla National Park, 2018

From left: Henry Aplin, David, unknown, Donald Bob, unknown, Eddie Jacob.

(Photo: Kate Connell)

From left: Henry Aplin, David, unknown, Donald Bob, unknown, Eddie Jacob.

(Photo: Kate Connell)

From years of fieldwork in the Gulf country, and throughout Australia, can you tell me the sorts of ways in which Aboriginal people tend to describe their sense of ‘connectiveness’ and the ways in which non-Indigenous people communicate their feelings of belonging and connectedness?

The big difference is spirituality in the land and waters, something widely known to be central to Aboriginal relations with country, though unfortunately Australians mostly base this idea on simplistic tropes and stereotypes. Aboriginal people report spiritual encounters, at times experienced through dreams and ephemeral sightings of unusual visual phenomena, in ways that are culturally distinctive. Belief in major Dreamings informs Gulf Country Indigenous worldviews and that intellectual perspective is mixed with the knowledge of great age of occupation by the ‘old people’. The old people are believed to continue to live in the land in spiritual form.

In contrast, Whitefellas in the Gulf Country speak of the productive value of land as a resource, and in terms of environmental awareness, many also embrace discourses about the ecological and aesthetic value of nature.

In my research, both Whitefellas and Blackfellas relate stories about events remembered that inform strong senses of place. The biographies of deceased and living relatives, peers and workmates are commonly part of the significance of landed identities for Whitefellas and Blackfellas. Important research on the diversities of belonging to locations across different migrant groups underlines the inadequacy of any simple notion of ‘non-Indigenous’ unity or homogeneity in terms of social identities connected with locations, lands and waters.

With respect to culturally significant places, is it possible for these two ways of being and belonging to co-exist? Can a place have many narratives, memories and feelings attached to it, or does this detract from the special relationships which Aboriginal people have to sites of significance?

In my opinion, there is no alternative to coexistence of diverse cultural connections to places, whether in the bush, the regional towns or the cities. Just how cooperative Indigenous and other senses of place and belonging may be will obviously vary with different locations, regions, histories and patterns of intercultural relations.

No doubt there will continue to be contestation over the meanings of place and land, but I’m optimistic about overlaps also continuing to inform cooperation in land management and pursuit of environmental sustainability. My aspiration in much of my applied work over many years has been to improve and increase economic beneficial outcomes for the Aboriginal people with whom I have carried out research. In my opinion, the future of cultural differences and overlaps in regard to landed identities will be influenced greatly by economic outcomes across the intercultural relationship.

The big difference is spirituality in the land and waters, something widely known to be central to Aboriginal relations with country, though unfortunately Australians mostly base this idea on simplistic tropes and stereotypes. Aboriginal people report spiritual encounters, at times experienced through dreams and ephemeral sightings of unusual visual phenomena, in ways that are culturally distinctive. Belief in major Dreamings informs Gulf Country Indigenous worldviews and that intellectual perspective is mixed with the knowledge of great age of occupation by the ‘old people’. The old people are believed to continue to live in the land in spiritual form.

In contrast, Whitefellas in the Gulf Country speak of the productive value of land as a resource, and in terms of environmental awareness, many also embrace discourses about the ecological and aesthetic value of nature.

In my research, both Whitefellas and Blackfellas relate stories about events remembered that inform strong senses of place. The biographies of deceased and living relatives, peers and workmates are commonly part of the significance of landed identities for Whitefellas and Blackfellas. Important research on the diversities of belonging to locations across different migrant groups underlines the inadequacy of any simple notion of ‘non-Indigenous’ unity or homogeneity in terms of social identities connected with locations, lands and waters.

With respect to culturally significant places, is it possible for these two ways of being and belonging to co-exist? Can a place have many narratives, memories and feelings attached to it, or does this detract from the special relationships which Aboriginal people have to sites of significance?

In my opinion, there is no alternative to coexistence of diverse cultural connections to places, whether in the bush, the regional towns or the cities. Just how cooperative Indigenous and other senses of place and belonging may be will obviously vary with different locations, regions, histories and patterns of intercultural relations.

No doubt there will continue to be contestation over the meanings of place and land, but I’m optimistic about overlaps also continuing to inform cooperation in land management and pursuit of environmental sustainability. My aspiration in much of my applied work over many years has been to improve and increase economic beneficial outcomes for the Aboriginal people with whom I have carried out research. In my opinion, the future of cultural differences and overlaps in regard to landed identities will be influenced greatly by economic outcomes across the intercultural relationship.

David (left) with Kelly Martin, Borroloola 2009

(Photo: Richard Martin)

(Photo: Richard Martin)

David (left) with Waany men Garrick George and Alec Doomadgee, and anthropologist Richard Martin, Mandululgi, 2017’ (Photo: Kate Connell)

Something you touched on before was the tensions that exist between some academic and applied social science work, especially with regards to anthropologists’ involvement in Aboriginal land rights. With academics accusing applied social scientists of perpetuating colonial pursuits by forcing Aboriginal people to conform to ‘Whitefella’ laws. However, on the other spectrum, applied anthropologists condemn academics for sitting in their armchairs at a distance from social issues. David, you’ve contributed to the discipline through both academic and applied work, so I wanted to ask you how you’ve navigated these tensions over your career?

My endeavour has been to remain full-time in the academy but bring applied work into that world. To my mind, it is arrogant elitism for academics to reject engagement with the worlds of government, the legal system and commerce beyond teaching and research. The academic treadmill can become an echo chamber that fails to promote results from studies outside of a small group of like-minded scholars.

I have always remained positive and engaged with academic writing, but I have also reflected on how I did not come from a family with any history of higher education. My parents were second generation migrants with ancestries from Jewish eastern Europe via one generation in England and their lives of practical work influenced me enormously. With hindsight, I realised some time ago that the idea of a working career remaining completely ensconced within the academic world was never comfortable for me.

So as opportunities arose to complete reports and surveys based on applied research, there was a considerable impetus to not reject those projects. Doing applied anthropology work involving Indigenous Australia, as well as environmental studies, means working within the constraints of the legal system and its politico-bureaucratic context. There is more freedom of writing outcomes and kinds of analysis when preparing academic publications. But it is the applied studies that promise actual outcomes for people, their legal rights, and albeit indirectly, also their economic circumstances.

The proposition that it is morally or politically more pure or superior to solely write critiques of the settler descendant society has never been convincing for me and it certainly is not convincing for the great majority of people for whom academic work remains distant and often compromised by a language of obscurity.

You are coming up to your 40-year anniversary as an anthropologist which is a significant milestone for you. So, I’m interested to ask you, how do you think anthropology has changed in Australia over this time?

For more than four decades the discipline has been changing as global thinking about the intellectual and moral standing of cross-cultural studies has been developing. When I was a student starting in the early 1970s there was a sense that older ways of doing anthropology, including ethnography and participant observation, needed change towards greater political commitment. And so Australian anthropology, along with Europe, the UK and north America, went down that route.

The false starts and successes of the changes over the subsequent decades have been rightly a subject of study and critique. It may sound like a cliché, but my feeling is to encourage recognition of the works that have gone before, alongside critiques, when they are warranted and productive. There can be a lure towards knocking down previous anthropological approaches and analyses in light of current fashions and political commitments. My aim is to also celebrate our intellectual and applied research inheritance that enables anthropologists to build on some wonderful work. It is important to make this point to students.

Why do you think anthropology is so important in today’s society?

Anthropology can draw attention to cultural difference, in the broader context of structural societal constraints and opportunities, in ways that are distinctive among other social science and humanities disciplines. While there are many potential pitfalls through the process of cross-cultural translation and related forms of analysis, there is also a promise of contributing to an understanding of a kind much needed in today’s world.

My own view is that anthropology’s value lies in addressing lives of people across all societies and all sectors of those societies. This approach is perhaps in some tension with work where a political commitment of the investigator constrains engagement with those seen to be on ‘the wrong side of history’. As evident in Australian anthropology, it remains that people of subaltern position are typically the focus for research and teaching, and there is no doubt about the importance of the desire to address matters of inequality being strong in the reasons many people choose to study the discipline.

I support a continuation of the discipline in forms that best suit changing circumstances both within and beyond the academy. In research concerning Australian intercultural relations and Indigenous affairs, there can be critique variously from both conservative forces and Indigenous activists. My approach is to respond positively when such critique is well-founded and to rebut criticism when it is simplistic and based on poorly supported accusative caricatures. The debates will necessarily broach both the achievements and failures of the discipline.

This is to foreshadow a continuing robust disciplinary tradition of research, teaching and applied social science that has a proud, if contested, history. There is no doubt that the legacies of Australia’s settler colonial society will inform anthropology’s future just as it has its past.

David discussing his long research history and personal connections in northwest Queensland, recorded in Mt Isa, March 2014.

David giving a keynote speech at the Anthrōprospective salon event ‘Ethics, Advocacy and Expertise; the role of Anthropology in Australia’ in September 2023.

David giving a keynote speech at the Anthrōprospective salon event ‘Ethics, Advocacy and Expertise; the role of Anthropology in Australia’ in September 2023.Interested to learn more about David’s work? Follow him here.

Connect with David via Linkedin.

To view David talking about his research in the Gulf watch a further interview on World101X.

Learn more about how David’s research in the ‘Gulf country’ is being used in the Waanyi UQ Digital Archive Project.

Connect with David via Linkedin.

To view David talking about his research in the Gulf watch a further interview on World101X.

Learn more about how David’s research in the ‘Gulf country’ is being used in the Waanyi UQ Digital Archive Project.