Finding a new “humanism” in COVID-19; a call for a new narrative

Words: Courtney Boag

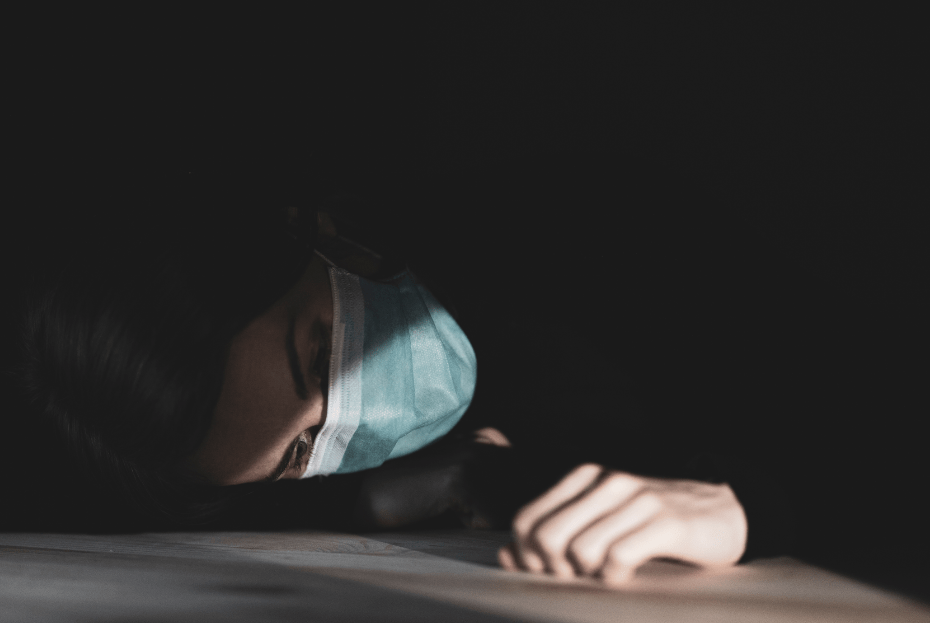

Images: Anthroprospective

29 May, 2020

“Indeed, the plethora of paths lie before us; however, the ways in which we respond to this crisis could move us in the direction of totalitarianism or solidarity. Shall we create new collective narratives of humanities resilience and engagement in the microbial world, or do we continue to listen to old narratives telling us of our fear towards it?”

Courtney Boag

While the cultural phenomenon of social isolation is hardly a new concern for us, the COVID-19 pandemic is challenging people all around the world to confront experiences of loneliness and questions of existentialism at an unprecedented scale. Social researcher, Hugh Mackey believes that our society has become increasingly “fragmented” as a result of “shrinking households”, relationship breakdowns and our burgeoning “reliance on technology” – namely social media. One only has to reflect upon the ways in which people, all around the world, relentlessly busy themselves with various monotonous undertakings to recognise how our own preoccupations with busyness act as a barrier to social cohesion. In fact, Mackey has likened humans to herds of animals, explaining that “humans react badly to being cut off from the herd”. Whether we consider ourselves as inherently extrovert or introvert, humans are inevitably social creatures. As Yuval Noah Harari writes in Sapiens, humanity’s development of complex modern societies was largely achieved as a result of our social capacity to create, spread and sustain grand myths. This ability to develop complex ideas, form social relationships, compete for status, and engage in gossip has become the biological blueprint of humanity; a DNA mutation which Harari argues allowed us to make an evolutionary leap like no other species. This concept of “Cognitive Revolution” is at the core of Harari’s provocative thesis that “it is our collected fictions that define us”.

While a growing tendency towards individualism is certainly becoming a feature of many societies around the world, our herd like mentality has captivated the interests of social researchers and psychologists over many years. Charlie Munger wrote in The Psychology of Human Misjudgement that ants, like humans, cooperate in great numbers but are wired to follow simple algorithms such as “follow-the-leader” which can cause them to literally march until their collective death. While of course, this insular observation cannot be likened to the human herd mentality there is a pertinent point to make here and that is that our ability to cooperate on such a macro scale can affect both positive and detrimental collective behaviours and hence, project various trend outcomes. Indeed, this fascinating aspect of human culture acts as a powerful tool of persuasion. If we collectively decide to alter the narratives we tell ourselves, we can inevitably alter behavioural change on a global scale. We can collectively decide that slavery, while being one of the world’s oldest economic institutions, is no longer acceptable and then work together to abolish the trafficking of people. Conversely, we can consent to the principles of capitalism and collectively choose to follow an economic system that may or may not reflect, nor accommodate for the realities of our day-to-day lives and requirements.

The COVID-19 pandemic has become a portal for social experimentation, a research exercise that is only afforded to us as a result of necessity. An opportunity to observe humanity’s herd mentality born from the declaration of a global emergency. While in “normal” times, these macro experiments would be impractical and inconducive to economic productivity, however, these are certainly not “normal” times. COVID-19 has been termed the crisis of our generation and it is rapidly becoming apparent that the decisions people and governments make in the coming weeks could profoundly shape the world for years to come. The narratives we foster during this time will be directly connected to the ways in which we make sense of this crisis and inevitably how we choose to respond to this predicament. The call to acknowledge that we are living during a global intervention or shared rite of passage that has uprooted our understandings of normality has presented itself to us. As Charles Eisenstein explains “to interrupt a habit is to make it visible; it is to turn it from a compulsion to a choice”.

While not attempting to undermine the destructive nature of this virus, the social responses to COVID-19 are demonstrating that when humanity is united for a common cause, rapid change is possible and, in many ways, inevitable. Indeed, many of the issues that face the world today can be prevented or mitigated, however, it is through human disagreement – the conflict of the various contradicting myths we have been told – that creates this dissonance. Fear of those that do not share our own myths or reflect our own realities creates social friction. Humans innately want to feel reassured that what they believe in and the principles by which they live their lives are considered the “true” path to follow. Consequently, when we observe others living by other principles and subscribing to alternative dogma, we can’t help but indulge in our own existential questioning. When this self-integration is harnessed in healthy moderation, it enables us to become more critical thinkers. More self-aware to our choices in life. The balance lies in accepting that narratives are interpreted in numerous ways and detaching from the nuances of these narratives that work to divide us. In coherency, humanity’s capacity to harness the power to solve multifaceted problems and work in harmony with others becomes boundless.

As a global pandemic, COVID-19 has affected us all in diverse ways and has emphasised those elements of our lives that are most important to us. It continues to influence the radical changes we are to make in our social behaviour; how we will engage with the economy, how we will decide to recognise and entrust the role of governments as decision makers and how we will interact with others. However, change will exist on a spectrum. For some, our entire livelihoods will change, many will be trying to find work and, in this process, may be challenged by questions of whether their previous careers were really serving them at all. Perhaps a great deal of us will be struck by these existential questions whether we have lost work or not and these reflections will guide their own unique trajectories following lockdown. Perhaps our consumer behaviours are changing already, possibly our relationships with friends and family have taken new shapes, maybe too, our relationships with loneliness will take new forms. Indeed, the plethora of paths lie before us, however, the ways in which we respond to this crisis could move us in the direction of totalitarianism or solidarity. Shall we create new collective narratives of humanities resilience and engagement in the microbial world, or do we continue to listen to old narratives telling us of our fear towards it? Can we create new desires to work together as a global community, or do we stagnant in new norms of social distancing while human contact becomes largely mediated through technology and masks?

Eisenstein explains that “historically, pandemics have forced humans to break from the past and imagine their world anew. This is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next”. The COVID-19 social phenomenon follows the same principles of a rite of passage for initiation; it has separated us from “normality”, which has seen us faced with numerous challenges and we have witnessed somewhat of a society breakdown. The passage is then made complete with a reintegration back into a state of new “normality”. However, when an initiate (in this instance, humanity) returns from this process, it is known by themselves and the rest of their community, that they are not the same person as before. Through this process, they have suffered, and through this suffering they have become more enlightened. Through this isolation and loneliness, they have been able to reflect more critically on who they are and who they need to become in order to return to their community as a leader – someone who will take on responsibilities to care for the community. These rites of passage are a fundamental feature of many traditional societies. This rite served to initiate boys into manhood and women into womanhood but, fundamentally, the purpose of this rite was to create an opportunity for people to experience suffering and isolation on such a level that they may become aware of a wisdom and resilience within themselves. As Rebecca Solnit describes in her novel, A Paradise Built in Hell, disaster can liberate solidarity. Through pain, loneliness, and loss, we can find love, companionship and new aptitudes with ourselves that we didn’t know we had.

The question then becomes, initiation into what? How are we prepared to change? And to what degree will we allow this rite of passage in our lives to change us? Psychologist, Susan David explains that “life’s beauty is inseparable from its fragility”. Life exists in a paradoxical state, we are comfortable until we have the carpet ripped from our feet, we feel safe until we have impeding threats forcing fear into our lives, we feel financially secure until the institutions we rely on lose their alleged power, we operate on autopilot until a moment in our lives requires us to wake up. Indeed, beauty in life exists because there is ugliness – this is the dualistic nature of our world. The Tao encourages us to live “openly with the apparent duality and paradoxical unity” that actually serves to bring us together, not drive us apart. Our innate desires to compartmentalise our lived experiences into simple notions of “good” and “bad” or “right” and “wrong” blinds us to the larger picture of life. It becomes pivotal during crises to recognise our capacity for emotional agility and wisdom so that we can navigate the ebbs and flows of life with self-acceptance, clarity and an open mind. As David reminds us “It’s about holding those emotions and thoughts loosely, facing them courageously and compassionately, and then moving past them to ignite change in your life.” To return to Harari’s notion that “it is our collected fictions that define us”; how do we want to use this opportunity to recreate our collective story, how do we want this event to define us. Shall we continue to move with the herd towards the path we were headed prior to this collective experience? Or will we – the initiates – create a new trajectory towards a novel “Cognitive Revolution”.

While a growing tendency towards individualism is certainly becoming a feature of many societies around the world, our herd like mentality has captivated the interests of social researchers and psychologists over many years. Charlie Munger wrote in The Psychology of Human Misjudgement that ants, like humans, cooperate in great numbers but are wired to follow simple algorithms such as “follow-the-leader” which can cause them to literally march until their collective death. While of course, this insular observation cannot be likened to the human herd mentality there is a pertinent point to make here and that is that our ability to cooperate on such a macro scale can affect both positive and detrimental collective behaviours and hence, project various trend outcomes. Indeed, this fascinating aspect of human culture acts as a powerful tool of persuasion. If we collectively decide to alter the narratives we tell ourselves, we can inevitably alter behavioural change on a global scale. We can collectively decide that slavery, while being one of the world’s oldest economic institutions, is no longer acceptable and then work together to abolish the trafficking of people. Conversely, we can consent to the principles of capitalism and collectively choose to follow an economic system that may or may not reflect, nor accommodate for the realities of our day-to-day lives and requirements.

The COVID-19 pandemic has become a portal for social experimentation, a research exercise that is only afforded to us as a result of necessity. An opportunity to observe humanity’s herd mentality born from the declaration of a global emergency. While in “normal” times, these macro experiments would be impractical and inconducive to economic productivity, however, these are certainly not “normal” times. COVID-19 has been termed the crisis of our generation and it is rapidly becoming apparent that the decisions people and governments make in the coming weeks could profoundly shape the world for years to come. The narratives we foster during this time will be directly connected to the ways in which we make sense of this crisis and inevitably how we choose to respond to this predicament. The call to acknowledge that we are living during a global intervention or shared rite of passage that has uprooted our understandings of normality has presented itself to us. As Charles Eisenstein explains “to interrupt a habit is to make it visible; it is to turn it from a compulsion to a choice”.

While not attempting to undermine the destructive nature of this virus, the social responses to COVID-19 are demonstrating that when humanity is united for a common cause, rapid change is possible and, in many ways, inevitable. Indeed, many of the issues that face the world today can be prevented or mitigated, however, it is through human disagreement – the conflict of the various contradicting myths we have been told – that creates this dissonance. Fear of those that do not share our own myths or reflect our own realities creates social friction. Humans innately want to feel reassured that what they believe in and the principles by which they live their lives are considered the “true” path to follow. Consequently, when we observe others living by other principles and subscribing to alternative dogma, we can’t help but indulge in our own existential questioning. When this self-integration is harnessed in healthy moderation, it enables us to become more critical thinkers. More self-aware to our choices in life. The balance lies in accepting that narratives are interpreted in numerous ways and detaching from the nuances of these narratives that work to divide us. In coherency, humanity’s capacity to harness the power to solve multifaceted problems and work in harmony with others becomes boundless.

As a global pandemic, COVID-19 has affected us all in diverse ways and has emphasised those elements of our lives that are most important to us. It continues to influence the radical changes we are to make in our social behaviour; how we will engage with the economy, how we will decide to recognise and entrust the role of governments as decision makers and how we will interact with others. However, change will exist on a spectrum. For some, our entire livelihoods will change, many will be trying to find work and, in this process, may be challenged by questions of whether their previous careers were really serving them at all. Perhaps a great deal of us will be struck by these existential questions whether we have lost work or not and these reflections will guide their own unique trajectories following lockdown. Perhaps our consumer behaviours are changing already, possibly our relationships with friends and family have taken new shapes, maybe too, our relationships with loneliness will take new forms. Indeed, the plethora of paths lie before us, however, the ways in which we respond to this crisis could move us in the direction of totalitarianism or solidarity. Shall we create new collective narratives of humanities resilience and engagement in the microbial world, or do we continue to listen to old narratives telling us of our fear towards it? Can we create new desires to work together as a global community, or do we stagnant in new norms of social distancing while human contact becomes largely mediated through technology and masks?

Eisenstein explains that “historically, pandemics have forced humans to break from the past and imagine their world anew. This is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next”. The COVID-19 social phenomenon follows the same principles of a rite of passage for initiation; it has separated us from “normality”, which has seen us faced with numerous challenges and we have witnessed somewhat of a society breakdown. The passage is then made complete with a reintegration back into a state of new “normality”. However, when an initiate (in this instance, humanity) returns from this process, it is known by themselves and the rest of their community, that they are not the same person as before. Through this process, they have suffered, and through this suffering they have become more enlightened. Through this isolation and loneliness, they have been able to reflect more critically on who they are and who they need to become in order to return to their community as a leader – someone who will take on responsibilities to care for the community. These rites of passage are a fundamental feature of many traditional societies. This rite served to initiate boys into manhood and women into womanhood but, fundamentally, the purpose of this rite was to create an opportunity for people to experience suffering and isolation on such a level that they may become aware of a wisdom and resilience within themselves. As Rebecca Solnit describes in her novel, A Paradise Built in Hell, disaster can liberate solidarity. Through pain, loneliness, and loss, we can find love, companionship and new aptitudes with ourselves that we didn’t know we had.

The question then becomes, initiation into what? How are we prepared to change? And to what degree will we allow this rite of passage in our lives to change us? Psychologist, Susan David explains that “life’s beauty is inseparable from its fragility”. Life exists in a paradoxical state, we are comfortable until we have the carpet ripped from our feet, we feel safe until we have impeding threats forcing fear into our lives, we feel financially secure until the institutions we rely on lose their alleged power, we operate on autopilot until a moment in our lives requires us to wake up. Indeed, beauty in life exists because there is ugliness – this is the dualistic nature of our world. The Tao encourages us to live “openly with the apparent duality and paradoxical unity” that actually serves to bring us together, not drive us apart. Our innate desires to compartmentalise our lived experiences into simple notions of “good” and “bad” or “right” and “wrong” blinds us to the larger picture of life. It becomes pivotal during crises to recognise our capacity for emotional agility and wisdom so that we can navigate the ebbs and flows of life with self-acceptance, clarity and an open mind. As David reminds us “It’s about holding those emotions and thoughts loosely, facing them courageously and compassionately, and then moving past them to ignite change in your life.” To return to Harari’s notion that “it is our collected fictions that define us”; how do we want to use this opportunity to recreate our collective story, how do we want this event to define us. Shall we continue to move with the herd towards the path we were headed prior to this collective experience? Or will we – the initiates – create a new trajectory towards a novel “Cognitive Revolution”.