Julie Finlayson brings Australian Native Title Anthropologists together to shape ideas for the Future

Interviewer: Courtney Boag

Images: Julie Finlayson

26 July, 2021

“It’s a calling, and if it’s a calling, then it’s something that permeates your whole orientation to the world, and how you understand your everyday life. Anthropology is not just about the exotic, it’s about anything and everything, as far as I’m concerned”

Julie Finlayson

Julie Finlayson is an anthropologist who has worked as an academic at La Trobe University and the Australian National University and within applied fields, including native title and cultural heritage work under the Northern Territory Aboriginal Land Rights Act, and across the native title system. Her early consultancy work in native title included an innovative program for early-career native title anthropologists funded by the National Native Title Tribunal and a survey in 2006 of the demography and skills of anthropologists in the native title sector. For several years, Julie ran fee-paying intensive courses through the University of Adelaide that were aimed at developing the skills necessary for native title practictioners. She consulted with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) through their Native Title Branch and was a member of the Minister’s team reviewing Native Title Representative Bodies across the country.

During her 8 years in the Australian Public Service, she worked in the Attorney-General’s Department funding Indigenous legal aid services, and in the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) within their Community Development Employment Project program. Her published research, aside from her native title papers published through the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR), includes a study of successful Indigenous organisations. Julie has also spent time working remotely in Wilcannia, where she was a manager and DJ for the local Indigenous community radio station. Currently, Julie is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Native Title Anthropology (CNTA) at the Australian National University where she has been instrumental in creating a professional network and educative workshops for native title anthropologists.

So, Julie, you’ve worked in various roles within Indigenous Affairs in Australia throughout your entire career, and over the past 20 years, you’ve been instrumental in establishing so many important initiatives and programs for early career native title anthropologists and practitioners. So, I really wanted to start from the beginning, and ask you how you first became involved in this sort of work and what your experience was like becoming an anthropologist.

Okay, so I didn’t know anything about anthropology when I was a young person, I was actually very interested in history. Early in my life, my mother collected small children under a scheme developed by Save the Children to transport them to kindergarten. I lived in a country town in Victoria, and growing up I went to school with many Aboriginal children, so I was able to observe something of Aboriginal people to some degree early on. When I became a history teacher, I was working in an area where there were many Aboriginal people living there and so I was able to introduce some components of Aboriginal history into the course I offered. I published some of that early work in the history teachers’ journal that led me on to work in the National Museum of Victoria, in the Education Service. During the time I was working there, the only historical material available (and this was in the late 1970s), was a kit for teachers to teach about the life of traditional Aboriginal people in the Western Desert. The museum displays were materials from the Northern Territory collected by the anthropologist Baldwin Spencer. Our education service library had ethnographic texts as well. But, having read Mervyn Meggitt’s book ‘Desert People’ it really piqued my interest in anthropology, and I then decided to leave teaching and go to the Australian National University, for further study in anthropology. The ANU was a very lively place for Australian Aboriginal anthropology. Professor Nic Peterson and Bob Tomkinson were there as well as a whole generation of people finishing their Ph.D., like Howard Morphy and Diane Bell.

Between 1981 and 1990, I completed a Master’s degree and a Ph.D. at the Australian National University, and during the latter part of my Ph.D., I took on consultancy work with the Central Land Council, and in cultural tourism, which again, was breaking new ground at the time. After that, between 1990 and 1992, I had moved to Brisbane and found work as a social planner for the Southeast Queensland Regional Council, linked to ATSIC which I’ll talk a little bit more about later. Wanting to move again between 1992 and 1996, I took up my first teaching position at La Trobe University. I had a sabbatical year in 1993 and I took a year off during my four-year contract with La Trobe to come up to CAEPR at the Australian National University. I worked there for a year and when my contract finished at La Trobe, I was offered a job back at CAEPR. I worked there from 96 to 2000. In that period CAEPR was funded largely by ATSIC and they had the requirement to produce what were called Discussion Papers, which were policy-orientated research publications around Aboriginal current policy issues, including economic development. I left CAEPR in 2000 to work as a consultant, which included some early native title research and the opportunity to consult with ATSIC. Later, at the end of 2004, I joined the ATSIC native title branch

In 2006, I took a year without pay from the Australian Public Service to research what made successful Indigenous organisations, which the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) published. The project was funded by a not-for-profit community development organisation, keen to promote good news stories about how and why Indigenous organisations were successful. All my case studies were service delivery organisations of some kind, ranging from health services to language centres, and demonstrated a suite of different kinds of organisations (in size, location, and purpose).

Shortly after my return to the Australian Public Service, I transferred to the Attorney-General’s Department to manage Indigenous Legal Aid Services. By 2009, and the imposition of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) or “intervention”, I was given responsibility for the delivery of the night patrols in the 72 communities identified under the NTER. I also developed a conference for the Aboriginal staff running the night patrols. The Night patrols were designed to promote community safety and were run by community members, often women. In 2009, I again transferred to another Commonwealth Department – Families and Communities, Housing and Indigenous Affairs (FaCHIS) to manage the community development section of the Community Development Employment Program (CDEP) at the time.

A community development aspect of the CDEP was a new aspect to the program and I think was very welcomed by the service providers since it provided them with funding that they could use for a range of specific issues pertinent to their operating environment. For instance, ranger programs, mentoring, education, and so on. There were no prescriptive guidelines around how they could use that money and I think that in a fairly prescriptive program overall, that was a breath of fresh air for most service providers. In 2012, I took up work at the Business Council of Australia. The Council and its members had initiated an Indigenous working group and organisations with large national footprints were interested in supporting Indigenous employment. They were keen to do this work in partnership with the Australian Government.

Once I left the Australian Public Service, I worked for six months in Burke in Western New South Wales. I was employed as a ‘community liaison officer’ for a service provider involved in a project to build two houses on a rent-to-purchase basis. Key to the project was Lend Lease, (a large construction company), the Australian Government, and a regional service provider. The project’s aim also involved designing houses suitable to their environment. If you’ve ever been to the far West of New South Wales, you’ll realise that the houses are not adapted to the environmental conditions: it’s very hot in the summer and few homes have insulation, and with very cold winter temperatures, again, there is no insulation. So, Lend Lease sent out their architect to talk to the local Aboriginal community about their houses. He also visited people in their homes and observed conditions and spoke with them about their needs. Ultimately he designed two local houses which ticked the boxes on the kinds of concerns people raised with him .. such things as privacy, safety, heating, and cooling, managing use of power, outdoor living space, storage, and so on, and the two houses were built by an Aboriginal building company. However, the project never went any further, unfortunately. One reason for this was that the cost of building in remote Australia is prohibitive and explains why cost-cutting measures take precedence. Getting appropriate materials is difficult and expensive, so these sorts of important projects don’t really get off the ground.

As the housing project came to completion, the service provider I was working for asked if I, “would you go down to Wilcannia and run their radio station?” I didn’t know anything about working on a radio station, but I could see that they wanted someone with literacy skills who could manage the reporting to the funding agencies. So, I took the job for 12 months and soon learned sufficient skills to operate as DJ Jules! It was quite an interesting experience in many respects, and I continue to keep in touch with the families and friends I made there. I was unemployed after leaving Wilcannia. I did some volunteer work at Vinnies and when the Centre for Native Title Anthropology job came up, for a one-year position initially, I applied. I’ve now been at CNTA for six years in September. As you can see, my employment history has been diverse. Occasionally I’ve thought that I could have continued on an academic trajectory but I’ve always wanted a variety of experiences and I think this aligns with my philosophy that anthropology can be broader than simply a traditional academic trajectory. And so, I’m glad that I’ve had a range of different opportunities and experiences with anthropology.

Okay, so I didn’t know anything about anthropology when I was a young person, I was actually very interested in history. Early in my life, my mother collected small children under a scheme developed by Save the Children to transport them to kindergarten. I lived in a country town in Victoria, and growing up I went to school with many Aboriginal children, so I was able to observe something of Aboriginal people to some degree early on. When I became a history teacher, I was working in an area where there were many Aboriginal people living there and so I was able to introduce some components of Aboriginal history into the course I offered. I published some of that early work in the history teachers’ journal that led me on to work in the National Museum of Victoria, in the Education Service. During the time I was working there, the only historical material available (and this was in the late 1970s), was a kit for teachers to teach about the life of traditional Aboriginal people in the Western Desert. The museum displays were materials from the Northern Territory collected by the anthropologist Baldwin Spencer. Our education service library had ethnographic texts as well. But, having read Mervyn Meggitt’s book ‘Desert People’ it really piqued my interest in anthropology, and I then decided to leave teaching and go to the Australian National University, for further study in anthropology. The ANU was a very lively place for Australian Aboriginal anthropology. Professor Nic Peterson and Bob Tomkinson were there as well as a whole generation of people finishing their Ph.D., like Howard Morphy and Diane Bell.

Between 1981 and 1990, I completed a Master’s degree and a Ph.D. at the Australian National University, and during the latter part of my Ph.D., I took on consultancy work with the Central Land Council, and in cultural tourism, which again, was breaking new ground at the time. After that, between 1990 and 1992, I had moved to Brisbane and found work as a social planner for the Southeast Queensland Regional Council, linked to ATSIC which I’ll talk a little bit more about later. Wanting to move again between 1992 and 1996, I took up my first teaching position at La Trobe University. I had a sabbatical year in 1993 and I took a year off during my four-year contract with La Trobe to come up to CAEPR at the Australian National University. I worked there for a year and when my contract finished at La Trobe, I was offered a job back at CAEPR. I worked there from 96 to 2000. In that period CAEPR was funded largely by ATSIC and they had the requirement to produce what were called Discussion Papers, which were policy-orientated research publications around Aboriginal current policy issues, including economic development. I left CAEPR in 2000 to work as a consultant, which included some early native title research and the opportunity to consult with ATSIC. Later, at the end of 2004, I joined the ATSIC native title branch

In 2006, I took a year without pay from the Australian Public Service to research what made successful Indigenous organisations, which the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) published. The project was funded by a not-for-profit community development organisation, keen to promote good news stories about how and why Indigenous organisations were successful. All my case studies were service delivery organisations of some kind, ranging from health services to language centres, and demonstrated a suite of different kinds of organisations (in size, location, and purpose).

Shortly after my return to the Australian Public Service, I transferred to the Attorney-General’s Department to manage Indigenous Legal Aid Services. By 2009, and the imposition of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) or “intervention”, I was given responsibility for the delivery of the night patrols in the 72 communities identified under the NTER. I also developed a conference for the Aboriginal staff running the night patrols. The Night patrols were designed to promote community safety and were run by community members, often women. In 2009, I again transferred to another Commonwealth Department – Families and Communities, Housing and Indigenous Affairs (FaCHIS) to manage the community development section of the Community Development Employment Program (CDEP) at the time.

A community development aspect of the CDEP was a new aspect to the program and I think was very welcomed by the service providers since it provided them with funding that they could use for a range of specific issues pertinent to their operating environment. For instance, ranger programs, mentoring, education, and so on. There were no prescriptive guidelines around how they could use that money and I think that in a fairly prescriptive program overall, that was a breath of fresh air for most service providers. In 2012, I took up work at the Business Council of Australia. The Council and its members had initiated an Indigenous working group and organisations with large national footprints were interested in supporting Indigenous employment. They were keen to do this work in partnership with the Australian Government.

Once I left the Australian Public Service, I worked for six months in Burke in Western New South Wales. I was employed as a ‘community liaison officer’ for a service provider involved in a project to build two houses on a rent-to-purchase basis. Key to the project was Lend Lease, (a large construction company), the Australian Government, and a regional service provider. The project’s aim also involved designing houses suitable to their environment. If you’ve ever been to the far West of New South Wales, you’ll realise that the houses are not adapted to the environmental conditions: it’s very hot in the summer and few homes have insulation, and with very cold winter temperatures, again, there is no insulation. So, Lend Lease sent out their architect to talk to the local Aboriginal community about their houses. He also visited people in their homes and observed conditions and spoke with them about their needs. Ultimately he designed two local houses which ticked the boxes on the kinds of concerns people raised with him .. such things as privacy, safety, heating, and cooling, managing use of power, outdoor living space, storage, and so on, and the two houses were built by an Aboriginal building company. However, the project never went any further, unfortunately. One reason for this was that the cost of building in remote Australia is prohibitive and explains why cost-cutting measures take precedence. Getting appropriate materials is difficult and expensive, so these sorts of important projects don’t really get off the ground.

As the housing project came to completion, the service provider I was working for asked if I, “would you go down to Wilcannia and run their radio station?” I didn’t know anything about working on a radio station, but I could see that they wanted someone with literacy skills who could manage the reporting to the funding agencies. So, I took the job for 12 months and soon learned sufficient skills to operate as DJ Jules! It was quite an interesting experience in many respects, and I continue to keep in touch with the families and friends I made there. I was unemployed after leaving Wilcannia. I did some volunteer work at Vinnies and when the Centre for Native Title Anthropology job came up, for a one-year position initially, I applied. I’ve now been at CNTA for six years in September. As you can see, my employment history has been diverse. Occasionally I’ve thought that I could have continued on an academic trajectory but I’ve always wanted a variety of experiences and I think this aligns with my philosophy that anthropology can be broader than simply a traditional academic trajectory. And so, I’m glad that I’ve had a range of different opportunities and experiences with anthropology.

Yeah, that’s such an impressive career. Just listening to you now sharing that detail it’s very interesting to reflect on the sort of different worlds and contexts that you’ve been exposed to. So, now you’re quite involved in a lot of native title work through your involvement with the Centre for Native Title Anthropology (CNTA). I think it would be beneficial if you could maybe provide a little explanation as to what native title is because some of our readers may be familiar with this term, and some may not be familiar.

Native title has been operating now for over 25 years. The Native Title Act (NTA) has been amended over that period, particularly in the first five to ten years, when issues of ‘certainty’ and other matters were challenged. There has also been changes in the native title system and the role of the institutions involved. The National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) for instance was a key player in the management of native title claims process, but over time their role has been greatly reduced. Nevertheless, for people seeking information about the native title claim process the NNTT website has excellent online information. You can also search for all the land claims and their status- those determined, and those registered, those with Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs), and so forth. Their website also deals with “frequently asked questions”.

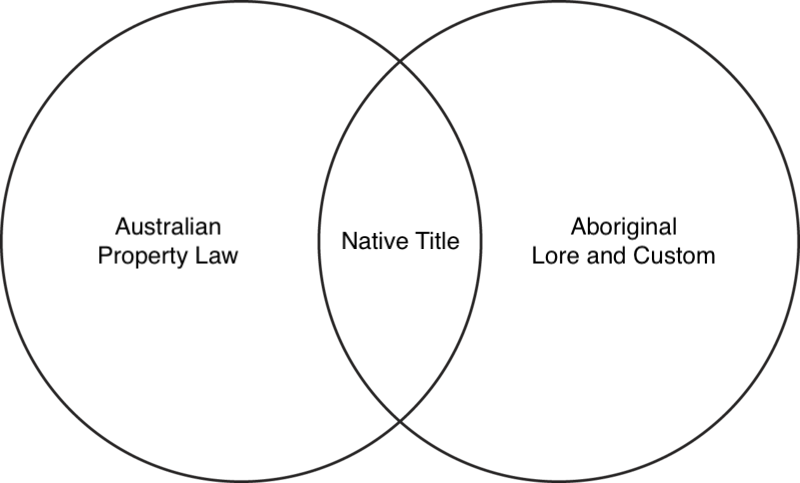

To understand what native title is, I like to think of two intersecting circles, where the overlapping part in the middle is what native title is. So, on the one hand, in one circle, you’ve got Aboriginal lore and custom and on the other side, you’ve got Australian Property Law. The intersection is where Australian law can recognise aspects of Aboriginal law, not the totality of it, but aspects of it, and that’s what native title is.

Sitting within that overlapping area is a range of evidentiary issues whereby the Australian legal system asks Aboriginal people to describe how they are connected to their country for the legal system to understand what ownership means and its alignment with aspects of the Australian property system. The NTA is beneficial legislation and that’s something that’s often forgotten, – it is meant for the benefit of Aboriginal people, the recognition and return of rights in land (and waters). However, proving native title is a complex process. For one, ownership is conditional on whether a Commonwealth or State/Territory law trumps it. Consequently, there is “exclusive possession” which means Aboriginal people have full native title rights, versus “non-exclusive possession” which means that Aboriginal people do not get exclusive rights to the area they are claiming. One of the earliest legal qualifications that was made in native title was to allow pastoral leases and Aboriginal law to coexistent. The overlay of other legislation and interests makes native title a complex and complicated Act.

Every state in Australia has its own concerns about Aboriginal people’s connection to country and this is where the evidentiary basis comes in whereby a “connection report” is asked of Aboriginal claimants; a document asking them to show their evidence. The document is written by anthropologists to establish the nature of the evidentiary basis an Aboriginal group has to the country (and or waters) they are claiming. And where a state finds the connection report acceptable on all the points, they might suggest a “consent determination” is drafted, as opposed to challenging the determination of a claim under litigation. A good example of a State that’s done a lot of consent determinations following the De Rose Hill case is South Australia.

Key questions that claimants must satisfy for native title are that you can describe what your society was like at the time of sovereignty and demonstrate your continuity with traditional lores and customs from that point. Of course, British sovereignty occurred at different times in different parts of the country, later in Queensland and northern Australia for instance, then in Tasmania or Victoria. You’ve also got to demonstrate your descent from what we call an “apical ancestor” as far back as written records can show. All are complex research issues. To assist with such research, organisations are funded by the Commonwealth under the NTA. These organisations are Native Title Representative Bodies and have been established to assist Indigenous people with native title claims and to help them navigate the complexities. In the early years of the NTA, there were 22 but their areas of responsibility have been paired down to 11.

In 1998, you were selected to work with the Minister for the re-recognition team for Native Title Representative Bodies. You’ve just provided an explanation as to what they are, so if you could go into a little bit more detail about how they operate, that would be great.

The Native Title Representative Bodies (NTRBs) were formed to assist Aboriginal people to make claims. In the very early days, Aboriginal people themselves were unclear about what was involved in claiming native title, understandably. In some cases, these organisations would ask people, “do you want to make a claim through native title?” etc, and 22 organisations emerged, but not unproblematically. Disputes arose because there was a notion that the boards of these organisations should be representative. So, let’s say, in area A of a native title claim, there are 16 different Aboriginal groups. For Aboriginal people, the concept of being ‘representative’ means I should have someone from my mob on the board. This would mean there should be 16 people on the board. But then the issue of how to prioritise which claim would arise and how do you make decisions around that? Whose claim is more deserving than another? What claims should take priority? Such tangles hovered around being ‘representative’ and raised all sorts of governance issues making disputes at the heart of the organisation very common. So, the Ministerial re-recognition process grew out of a view that the system wasn’t working properly.

ATSIC formed two teams comprising a lawyer, an anthropologist, and an accountant, and these teams were led by a government worker. The two teams were allocated to different regions and organisations Australia-wide for about nine or 10 months. Each team met with an organisation, spent two days with them and based on a huge amount of reporting prepared prior to the visit, were asked questions to clearly understand their capacity to function as a Native Title Representative Bodies. Each team compiled written notes through our observations and discussions and these were then sent to Canberra. A brief was then made to the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs for his decision on whether that organisation should continue to operate as a ‘recognised body’ or not. Oddly enough at the time the area in the Gulf of Carpentaria and Mount Isa was deemed as an ‘unrecognised’ area. After finishing my work with the re-recognition team, I worked in the Gulf in my capacity as a consultant to assist with claim management. Once a month I would fly in from Canberra and a lawyer would fly in from Alice Springs and together we would supervise consultant researchers working in the area and talk with the local Aboriginal people on the ground about their claims, and so forth. Eventually, that area did get recognised. During this period, another organisation was formed called Native Title Service Providers (NTSPs). Such organisations had the same roles and powers under the NTA but were incorporated differently.

All these were fascinating experiences that gave me a fabulous overview of how people were dealing with claims, and how they structured their organisations, and so forth. Over time, such native title service organisations have become far more sophisticated and their capacity to deliver outcomes has improved expediently, along with their governance. Overall, time brings maturity.

That’s really interesting. So, clearly native title operates within quite a legal framework. So, I’m wondering, Julie, how did anthropologists become involved in this sort of work? And what role do they play within the native title process?

Native title anthropologists work within the legislation (NTA) and with lawyers. I remember when I worked at CAEPR in the early-mid 1990s and we held workshops for anthropologists to talk about what this new thing called ‘native title’ is and to discuss how we were going to deal with it? What would be our role in it, and so on. The anthropologists working at CAEPR during this time put on several workshops and published the papers given. We charged people $20 to attend to cover the morning tea and lunch; they were great occasions because the discussions were open, and frank. Nobody had done this sort of work before, and we really didn’t know how we were going to approach it.

Over time, tensions have arisen between anthropologists and lawyers about how to deal with key concepts in native title and there’s been tensions around research methods, research issues, and how to prepare the documents and so on. There’s also been tensions, I think, in how organisations manage staff anthropologists and lawyers, and, in some organisations, hierarchical management structures and quasi-legal practices have not always been productive. In native title work, anthropologists are frontline people. They’re the ones who talk to people and form relationships with claimants and who understand the political and familial tensions in groups. They must ask claimants all sorts of questions, including specific matters about relationships to country, and who has rights to conduct certain activities on country and who doesn’t, and so on; in the process, anthropologists develop strong relationships with people. Lawyers might develop such social connection too, but generally, they come after the anthropological inquiries and have the role of interrogating the research material in relation to the evidence required under the NTA.

The lawyers may not always understand things anthropologists learn in the development of relationships; understanding, for example, the ways that certain people will describe their connection, or the nature of body language when they don’t want to talk about something because it has implications for their cultural relationships with others in their own group. These kinds of nuanced understandings are not always evident to lawyers bent on conformity with the legislation and so they don’t always see the totality of the situation. So, anthropologists, I think, play a critical role in the ‘translation space,’ if you like, working on the front line with Aboriginal people, understanding their laws and customs, bringing this into the translation space where it can be articulated for the lawyers and in relation to the legislation. Of course, anthropologists need to be mindful that it is not their role to decide whether people have native title or not; that is the lawyer’s role and that of the court. Anthropologists gather the evidence and provide that evidence to the court. The judge then adjudicates the claim based on the evidence.

One of the enduring issues between the lawyer and anthropologist relationship in native title is that we’ve still got to get to that point where people can see that they need to work collaboratively. Last year, CNTA did work on compensation looking at questions like;

- how are we going to understand compensation?

- What should a brief to an anthropologist have in the Terms of Reference (ToRs)?

We had the advantage of working with a draft brief and invited the CNTA’s current Director, Emeritus Professor David Trigger to join the discussion. His view was that some of the questions in the ToRs for a compensation claim were difficult for an anthropologist to answer and that best results needed a collaborative approach. New ground had to be broken- just as it had when native title began.

Images from a Centre for Native Title Anthropology Conference in September 2023 that Julie organised

These conferences play a pivitol role in providing anthropologists with professional development opportunities in native title within Australia.

Yeah, that’s interesting what you’ve just mentioned about compensation and working in multi-disciplinary teams. Something that I’ve been reading about recently is the potential for economists to become involved in these sorts of discussions. But of course, anthropologists and lawyers don’t always see eye-to-eye and I can imagine that economists will have their own perspectives that may not align with anthropologists either. So, concepts of cultural loss are going to be very complex, and it will be difficult to compensate for cultural loss, I mean how do you put a price on that? Are these sorts of discussions being had at the Centre for Native Title Anthropology now?

Very much. CNTA has a tab on the website with resources for compensation if people want to learn more. We have also uploaded several podcasts onto the website and there is an episode where we talk with Justice Mansfield about compensation, which is worth exploring.

I can recognise that native title anthropology would come with its own set of challenges considering the legal requirements that practitioners need to work within. So Julie, I’m interested to know whether you think the amalgamation of law and anthropology in Australia has brought about any challenges in how cross-cultural perspectives and values are understood and recognised in Native Title claims?

Yes, I’m not sure how to answer that question, Courtney. I think in many cases, the shifts in public perceptions around Aboriginal people’s connections to country have occurred largely in the white middle-class. There is now greater sensitivity around how we understand Aboriginal people’s feelings about country and their connections to places. I think there’s been a big shift in the public perception of that. There’s a lot of books available now explaining how Aboriginal rangers look after country and what “caring for country” means.

However, in the post-determination space, many successful claimant groups are wondering what they can actually do with recognition of title to land. In some cases, new industries like carbon farming and ranger programs have been successful. But there is only a small percentage of people who can be involved in such industries and only certain areas within Australia where these sorts of programs can occur. So, to find economic value and develop an economic purpose for making something of your title is, I think, a work in progress. There are all sorts of wider questions successful claim groups are asking, like;

Many of these are community development questions.

Could you describe what ‘post-determination’ means Julie?

Yes, so a determination is made for native title by the Federal or State/Territory government – either as a consent determination or via a litigated case. If a claim is successful, the group will become recognised as the native title holders and they will be given title to that country. Rights commonly found are those which enable a group or its members to hunt, camp, take resources, perform ceremonies, and so on. Simply, “post-determination” just means a claim that has been successfully determined.

I’m interested to know Julie, how is cultural change within native title considered? Are there accommodations made by the legal system to consider the impacts of colonisation on Aboriginal culture in Australia?

Not really in native title, because what you need to consider in native title are the relationships between a particular group of people to specific land and waters. A case that immediately comes to mind is the Yorta Yorta case where it was said that the “tide of history had washed away” their connection to country and water. There are people who would like to revise the way that case was concluded. But in terms of the wider impacts of colonialism and loss of cultural practices in how people live, this is not necessarily part of native title, as I understand it, it’s about the specificity of people’s relationships to country today. On the other hand, the loss of connection to country under colonial practices might be grounds for a compensation claim.

A debate that I think has really been brewing over the past 25 years, is the criticism that native title anthropologists have received from their academic colleagues, and these condemnations being that, you know, native title anthropologists are ‘compromised’. As someone who has had extensive experience within both the academic and applied fields, can you weigh in on this debate? Can you explain what may be implied by this assumption that native title anthropologists are ‘compromised’?

Yes. I think this idea came from a particular group of academic anthropologists who were opposed to the “state” and saw things as black and white, for instance, either you work for the state or you don’t, and if you worked for the state, you were part of the ‘handmaiden of colonialism’. However, I think we’ve developed a much more mature attitude now. During the earlier stages of native title, I think that anthropologists who were doing assessments for the State were seen in that light, you know, like you’ve gone over to the dark side. Whereas I think part of the issue is that anthropologists need to present themselves as people who are inquiring into things, not necessarily advocates. One of the things that has changed this oppositional approach, I think, is that many academic anthropologists now also work in native title, doing assessments for the State. I think, during those early stages in native title, these issues were constantly bubbling to the surface and had continuity with issues anthropologists had previously faced during their involvement in the early land rights cases. Yet the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (ALRA) is a different kind of process to native title. It might be seen as more benign since it is an administrative inquiry unlike the legislative framework in native title.

Another factor, of course, Courtney, is that most young anthropologists with anthropology degrees end up working in Native Title Service Providers and Representative Bodies, because these are arenas of employment and there are very few jobs in the university sector. Also, the conditions for university teaching and research are onerous these days, and not very supportive. So, a lot of young people who want to use their anthropology degrees begin their careers in claim research.

Very much. CNTA has a tab on the website with resources for compensation if people want to learn more. We have also uploaded several podcasts onto the website and there is an episode where we talk with Justice Mansfield about compensation, which is worth exploring.

I can recognise that native title anthropology would come with its own set of challenges considering the legal requirements that practitioners need to work within. So Julie, I’m interested to know whether you think the amalgamation of law and anthropology in Australia has brought about any challenges in how cross-cultural perspectives and values are understood and recognised in Native Title claims?

Yes, I’m not sure how to answer that question, Courtney. I think in many cases, the shifts in public perceptions around Aboriginal people’s connections to country have occurred largely in the white middle-class. There is now greater sensitivity around how we understand Aboriginal people’s feelings about country and their connections to places. I think there’s been a big shift in the public perception of that. There’s a lot of books available now explaining how Aboriginal rangers look after country and what “caring for country” means.

However, in the post-determination space, many successful claimant groups are wondering what they can actually do with recognition of title to land. In some cases, new industries like carbon farming and ranger programs have been successful. But there is only a small percentage of people who can be involved in such industries and only certain areas within Australia where these sorts of programs can occur. So, to find economic value and develop an economic purpose for making something of your title is, I think, a work in progress. There are all sorts of wider questions successful claim groups are asking, like;

- if we have an income stream, what can we do with it?

- How can we create a future for young people?

- How do we make decisions on behalf of everybody?

- Where some people cannot get an income stream, how can we benefit the wider group?

Many of these are community development questions.

Could you describe what ‘post-determination’ means Julie?

Yes, so a determination is made for native title by the Federal or State/Territory government – either as a consent determination or via a litigated case. If a claim is successful, the group will become recognised as the native title holders and they will be given title to that country. Rights commonly found are those which enable a group or its members to hunt, camp, take resources, perform ceremonies, and so on. Simply, “post-determination” just means a claim that has been successfully determined.

I’m interested to know Julie, how is cultural change within native title considered? Are there accommodations made by the legal system to consider the impacts of colonisation on Aboriginal culture in Australia?

Not really in native title, because what you need to consider in native title are the relationships between a particular group of people to specific land and waters. A case that immediately comes to mind is the Yorta Yorta case where it was said that the “tide of history had washed away” their connection to country and water. There are people who would like to revise the way that case was concluded. But in terms of the wider impacts of colonialism and loss of cultural practices in how people live, this is not necessarily part of native title, as I understand it, it’s about the specificity of people’s relationships to country today. On the other hand, the loss of connection to country under colonial practices might be grounds for a compensation claim.

A debate that I think has really been brewing over the past 25 years, is the criticism that native title anthropologists have received from their academic colleagues, and these condemnations being that, you know, native title anthropologists are ‘compromised’. As someone who has had extensive experience within both the academic and applied fields, can you weigh in on this debate? Can you explain what may be implied by this assumption that native title anthropologists are ‘compromised’?

Yes. I think this idea came from a particular group of academic anthropologists who were opposed to the “state” and saw things as black and white, for instance, either you work for the state or you don’t, and if you worked for the state, you were part of the ‘handmaiden of colonialism’. However, I think we’ve developed a much more mature attitude now. During the earlier stages of native title, I think that anthropologists who were doing assessments for the State were seen in that light, you know, like you’ve gone over to the dark side. Whereas I think part of the issue is that anthropologists need to present themselves as people who are inquiring into things, not necessarily advocates. One of the things that has changed this oppositional approach, I think, is that many academic anthropologists now also work in native title, doing assessments for the State. I think, during those early stages in native title, these issues were constantly bubbling to the surface and had continuity with issues anthropologists had previously faced during their involvement in the early land rights cases. Yet the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (ALRA) is a different kind of process to native title. It might be seen as more benign since it is an administrative inquiry unlike the legislative framework in native title.

Another factor, of course, Courtney, is that most young anthropologists with anthropology degrees end up working in Native Title Service Providers and Representative Bodies, because these are arenas of employment and there are very few jobs in the university sector. Also, the conditions for university teaching and research are onerous these days, and not very supportive. So, a lot of young people who want to use their anthropology degrees begin their careers in claim research.

So, you’ve mentioned the Land Rights Act a few times, and I know that in your early consultancy work in native title and cultural heritage, you had the opportunity to operate under the Northern Territory Aboriginal Land Rights Act. This was a pretty landmark piece of legislation for Aboriginal people in Australia. Could you provide a general overview for our readers about what this Act meant for Aboriginal people and how it came about?

In the 1970s there was a view that Aboriginal people should have land rights- just as many native Americans, Canadians and Māori’s did. It was also a time of social reformation in western societies with a lot of reimagining of social formations and constructs. The land right inquiry which was to lead to a land rights Act was undertaken by Justice Woodward, and he engaged Nic Peterson as his anthropological advisor. Nic went to Canada to look at the system of land claims processes there. Justice Woodward, drawing on input from Nic, developed legislation for land rights in the Northern Territory (then still managed by the Commonwealth government).

The Aboriginal Land Rights Act (ALRA) has different kinds of definitions from what is in native title. Under ALRA, Aboriginal groups must be able to form what’s called a “local descent group”, and then demonstrate that they have common spiritual affiliations to sites in the specific land and that these affiliations give that local descent group a primary spiritual responsibility for those sites and country. A third prong is that under Aboriginal tradition, the group is entitled to hunt and forage, as a right, over that land. So, there are very clear three-pronged definitions of what a Traditional Owner is, and if you could establish that through the land rights inquiry process, then land rights would be granted.

During the 1970s and 1980s, successful claim groups were establishing outstations to move away from the large communities established in the 1950-60s which brought numerous social problems as different groups were thrown together for the first time. Aboriginal people wanted to return to their own countries in smaller family groups. Land rights enabled people to do that in the 1980s. The land commissioner always had an anthropological advisor; anthropologists I remember were Deborah Bird Rose and John Avery, amongst many others. These experts worked with the judge to help him understand concepts, what was being said by the Aboriginal witnesses in Aboriginal English, and so forth, and hearings were always held on country. The (judges) Land Commissioners went out on country for the hearings and visited all the sites. But even though that was a beneficial process, the Northern Territory Government fought every one of those claims tooth and nail.

The ALRA really set up the Northern and Central Land Councils to perform certain functions such as the preparation of the claims, the management of the land, and the administrative issues following a successful claim. A key function in this work was informed consent, ensuring that decision-making done by the land council on behalf of the Aboriginal people they represent had to have been done through consultation. In a way, the land councils act in a role for people who don’t have the funding, and specialised skills to be engaging with wider society’s administrative processes. One of the issues that has come to the fore over time for land councils is, what to do with country? It is the same question that confronts native title holders. In the Territory now there is something like 55 to 60% of the land now Aboriginal owned.

Julie, you’ve also spent some time working with what was called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, otherwise known as ATSIC. This was an important development in Australia established under the Hawke government, which allowed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to formally become more involved in government processes that directly affect their lives. I’d love to learn more about what your role in this initiative was, and how effective the commission was in improving the lives of Aboriginal people in Australia?

I see the original intent of ATSIC as an opportunity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to have their voices heard during decision-making, from the bottom up, where regional councils could inform commissioners at top of the hierarchical structure with their concerns. Regional areas were given budgets for various programs like health, education, community safety, land management programs, and a whole range of things. But what is often not understood was that the mainstream departments also had those budgets and were still responsible for the delivery of those sorts of services in those kinds of areas too. The budget that ATSIC had was more limited so their capacity to do certain things was limited, even though in the politicisation of ATSIC they were held as totally responsible when they weren’t, they didn’t have their hand on every lever. So, there were a lot of upsides to ATSIC, such as the capacity through a tiered structure to influence decision making in policy and programs, and for engagement between central and regional teams where issues of concern to Indigenous communities could be recognised. This linkage is something that’s been lost in current decision making in my view. There is no representative voice coming up from the regions as there was when ATSIC operated. The people who worked in the bureaucracy then were also people who had experience working with Aboriginal people and who were keen to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. There were a lot of positives.

On the downside, to vote in an ATSIC election you had to be on the Australian electoral roll and a lot of Aboriginal people weren’t, and still aren’t today, unfortunately. When working at the radio station in Wilcannia, I used to encourage local Aboriginal people at election time to get on the roll, because Aboriginal advocates fought for Indigenous rights to vote. I mentioned men like Bill Ferguson and many others who fought for these rights in the 1930s and 1940s. But unless you’re on the Australian electoral roll you couldn’t vote in the ATSIC elections. Inevitably it could mean that someone might be elected with 25 votes or something ridiculous like that. So, it was imperfect in that way. I think that another disadvantage of ATSIC at times was an internal “boys’ club” operating at the top with key individuals wielding undue influence that wasn’t healthy for the Commission overall. On the other hand, there were significant female CEOs like Pat Turner and Lowitja O’Donoghue. Yet it was the downsides, which enabled John Howard to run ATSIC down in name and action and then dismember it.

I joined ATSIC in December 2004- in its dying throes. It collapsed early in 2005. I saw many of my new colleagues skedaddle to different positions outside of Canberra given they knew the fallout coming. In preparation of ATSIC’s demise, a group had been formed in the Department of Immigration and Indigenous Affairs, called the Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination, and once the machinery of government change occurred when ATSIC folded this group was brought in. Many public servants who had been working in different program areas (e.g Indigenous health or education) were moved into mainstream Health or Education Departments. A lot had terrible experiences since they were treated like pariahs because it was publicly said that ATSIC was rorting funds and that the people working for ATSIC were incompetent and spoilers, and so on. Staff who had worked in ATSIC had a very, very difficult time transitioning to their new departments.

For people working in native title, where I was working at the time, the transition wasn’t easy for them either because people from the Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination basically saw us in the same way too. This made it difficult to work productively during the transition. The National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) has not replaced the regional offices which existed under ATSIC, nor the decision-making processes with regional offices. Many Aboriginal people have lost confidence in the government. There are no formal channels for them to contribute. ATSIC might have had weaknesses but, really, the baby and the bath water were thrown out together.

Yeah, ok. That’s quite disheartening to hear about models that had a lot going for them and then just being disbanded like that. So, Julie, over the past six years, you’ve been extremely instrumental in establishing a lot of programs for supporting native title anthropologists to gain the skills that are necessary to navigate what is a very complex environment, as we’ve talked about, and I’d love to know a little bit more about what the Centre for Native Title Anthropology does and why you think it’s so important to offer these development initiatives to native title anthropologists.

The Centre for Native Title Anthropology (CNTA) has been operating for 11 years at the Australian National University and is funded by the Attorney-General’s Department under a competitive grant program. This anthropology grant program had its genesis in complaints from service providers, that one of the reasons for the backlog of claims before the court was due to insufficiently experienced anthropologists available to progress claims. The courts really wanted anthropologists at a mid-senior level who could work as expert witnesses to the court, and they wanted educative courses to help upskill anthropologists at all career stages. Earlier it was thought university courses could provide the upskilling. But as we now see, universities are not interested in these sorts of courses. In fact, as we can see, they’re paring back on anthropology courses in general. There is also a prevalent view amongst universities that only Aboriginal people should teach subjects about Indigenous people. CNTA, in a way, now fills a gap by providing an educative vehicle for native title practitioners where nothing is available at any of the universities that I’m aware of. I think CNTA plays an important educative role, it provides collaborative networks and support for practitioners to meet colleagues and talk about practical problems arising in their native title work.

So, Julie, the native title era has been influencing the lives of Aboriginal people in Australia since 1994 in very profound ways. Whether it’s achieved its goal of providing Aboriginal people with recognition or not, I mean, those outcomes exist on a spectrum across the country, but I’m interested to know how far away you think we are as a nation towards achieving genuine reconciliation with the First Peoples of this land, and what do you think is needed to get us from here to there?

Okay, there’s a couple of points to make. First, non-Indigenous people feel differently about Aboriginal issues and Aboriginal recognition across the country. For example, I think on the eastern seaboard and middle-class people are interested in Aboriginal lifeways and life stories and they support diverse forms of symbolic recognition, from a Welcome to Country, to acknowledgments on our local TV stations, flying the Aboriginal flag outside key institutions, and so on. Non-Indigenous people are keen to be involved I think; they are also keen to meet Aboriginal people even if they’re not quite sure how to do that, or to understand some of the complexities and conflicting things within this space. They value Aboriginal art. They embrace Aboriginal tourism.

In country areas, by contrast, I think the enthusiasm is not so even; for example, there are farmers finding stone tools in their paddocks some of whom value these objects and want to deposit them in museums. While others are frightened and concerned it will lead to a claim over their country. It indicates that native title is still not always understood by the general population. But I do think we’ve come a long way in my lifetime. One of the biggest steps forward, I think, were the outcomes of the Whitlam government in the mid-1970s, when Indigenous Legal Aid was implemented, along with Indigenous health services, and the Australia Council funding Indigenous art and literature. The latter led to a plethora of Aboriginal biographies. One of the first of such books I read in that period was by Bobbie Hardy – ‘The world owes me nothing’. It’s about an Aboriginal shearer in Western New South Wales describing his life and his struggles. So suddenly, the wider society had the opportunity to read about the experiences of people previously unknown to them.

So native title has made a big contribution to Aboriginal status, I think. The right to negotiate and to sit at the table with miners and developers for the first time gave Indigenous Australians the opportunity to talk about their country and raise their concerns, where before their views and feelings were overlooked or dismissed. I remember one of the first claims I worked on and during the first hour of the hearing, the group wanted to unload about the frustrations that they had when no one took them seriously, no one listened to their concerns. Moving from a point where people felt that they didn’t have a voice to say anything to a situation where they have got a right to say something and to make decisions about their country, that is important.

I think the other thing that has changed is the nomenclature around Australian Indigenous people. So you know, when I started out in Aboriginal Affairs Aboriginal people was just a cover term for everyone around Australia, then we started identifying people as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, and now we have language group names relating to countries, and more recently we use the term, First Nations. Our lens, if you like, was very generalised and now it is becoming more nuanced such that we appreciate specificities, locations, languages, and Indigenous histories, which goes again, to what came out of the land rights era. As a result of the land rights era, for the first time, historical records were compiled to chronicle the history of groups and their country, and this history was being revealed and made publicly accessible.

We’ve come a long way, a very long way. Another step forward has been accepting Aboriginal people and their cultural background rather than saying people are 1/6 this and 1/7 that. Aboriginal people now have the choice to identify or not, and to live the kind of life they want, as an Aboriginal person or as a person of Aboriginal descent. There are Indigenous people, for example, who attend university who have Aboriginal descent but don’t want to be identified in that way. Amongst artists there are some who say, “I don’t want to be called an Aboriginal artist, I just want to be called an Australian artist”. So, there are many shifts going on.

Yeah, that’s interesting Julie. So that leads me to my last question, Julie. What do you think anthropology has to offer the future of humanity?

Look, I feel very positive about that because I think anthropology gives you a set of skills, which you can use in any context. Some years ago, Professor Annette Hamilton, an early researcher in Aboriginal Australia and who wrote a fabulous book on child-rearing in the Western Desert, gave a keynote address at an Australian Anthropology Society conference. She posed a question not dissimilar to what you’ve just asked; “why aren’t anthropologists explaining more about human nature and all the permutations that arise?” “Why have historians and psychologists got the upper hand here?”

I think that’s a question that’s still very relevant today and it goes in some ways, perhaps, to something about the discipline but also to the self-selection of personalities that go into the discipline. Often anthropologists are very individualistic, even loners, given fieldwork is generally conducted alone. And I think that, in returning to our earlier discussion about applied anthropology, I remember someone who had submitted an article about applied anthropology to one of our journals and they were subsequently told that it was not written in a way sufficient for an academic audience. So, we’ve put boundaries around the way we think anthropology should engage with people without understanding that anthropology is a broad church, and we need to write for different audiences.

Peter Sutton has written two books now for a broad audience; The Politics of Suffering, and now, The Hunters and Gatherers or Farmers Debate, and we don’t do enough of that. We write for our colleagues more than we write for the wider audience, and I think, there’s going to be a problem in that, because our colleagues, as we have spoken about earlier, are becoming a smaller and smaller cohort in the academy. We know too that it can take up to two years to publish an article in an academic journal, whereas if we were writing for The Conversation, or writing a book for a general readership, we’ve got more capacity to influence through those sources than we do by sticking to an academic pathway. However, if you’re in the academy, that’s the only pathway that gets you the recognition that you need for your own advancement.

So, what does anthropology have to offer? Well, someone once said to me, it’s a calling, and if it’s a calling, then it’s something that permeates your whole orientation to the world, and how you understand your everyday life. Anthropology is not just about the exotic, it’s about anything and everything, as far as I’m concerned. And it’s interesting to use that anthropological lens on your everyday experience, you know, sitting in the doctor’s waiting room, and observing how people comport themselves there? How are decisions made? What are the power structures you can see operating here? All those kinds of concepts and observations are relevant to the way we understand our life and the lives of others. So, that would be my take.

In the 1970s there was a view that Aboriginal people should have land rights- just as many native Americans, Canadians and Māori’s did. It was also a time of social reformation in western societies with a lot of reimagining of social formations and constructs. The land right inquiry which was to lead to a land rights Act was undertaken by Justice Woodward, and he engaged Nic Peterson as his anthropological advisor. Nic went to Canada to look at the system of land claims processes there. Justice Woodward, drawing on input from Nic, developed legislation for land rights in the Northern Territory (then still managed by the Commonwealth government).

The Aboriginal Land Rights Act (ALRA) has different kinds of definitions from what is in native title. Under ALRA, Aboriginal groups must be able to form what’s called a “local descent group”, and then demonstrate that they have common spiritual affiliations to sites in the specific land and that these affiliations give that local descent group a primary spiritual responsibility for those sites and country. A third prong is that under Aboriginal tradition, the group is entitled to hunt and forage, as a right, over that land. So, there are very clear three-pronged definitions of what a Traditional Owner is, and if you could establish that through the land rights inquiry process, then land rights would be granted.

During the 1970s and 1980s, successful claim groups were establishing outstations to move away from the large communities established in the 1950-60s which brought numerous social problems as different groups were thrown together for the first time. Aboriginal people wanted to return to their own countries in smaller family groups. Land rights enabled people to do that in the 1980s. The land commissioner always had an anthropological advisor; anthropologists I remember were Deborah Bird Rose and John Avery, amongst many others. These experts worked with the judge to help him understand concepts, what was being said by the Aboriginal witnesses in Aboriginal English, and so forth, and hearings were always held on country. The (judges) Land Commissioners went out on country for the hearings and visited all the sites. But even though that was a beneficial process, the Northern Territory Government fought every one of those claims tooth and nail.

The ALRA really set up the Northern and Central Land Councils to perform certain functions such as the preparation of the claims, the management of the land, and the administrative issues following a successful claim. A key function in this work was informed consent, ensuring that decision-making done by the land council on behalf of the Aboriginal people they represent had to have been done through consultation. In a way, the land councils act in a role for people who don’t have the funding, and specialised skills to be engaging with wider society’s administrative processes. One of the issues that has come to the fore over time for land councils is, what to do with country? It is the same question that confronts native title holders. In the Territory now there is something like 55 to 60% of the land now Aboriginal owned.

Julie, you’ve also spent some time working with what was called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, otherwise known as ATSIC. This was an important development in Australia established under the Hawke government, which allowed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to formally become more involved in government processes that directly affect their lives. I’d love to learn more about what your role in this initiative was, and how effective the commission was in improving the lives of Aboriginal people in Australia?

I see the original intent of ATSIC as an opportunity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to have their voices heard during decision-making, from the bottom up, where regional councils could inform commissioners at top of the hierarchical structure with their concerns. Regional areas were given budgets for various programs like health, education, community safety, land management programs, and a whole range of things. But what is often not understood was that the mainstream departments also had those budgets and were still responsible for the delivery of those sorts of services in those kinds of areas too. The budget that ATSIC had was more limited so their capacity to do certain things was limited, even though in the politicisation of ATSIC they were held as totally responsible when they weren’t, they didn’t have their hand on every lever. So, there were a lot of upsides to ATSIC, such as the capacity through a tiered structure to influence decision making in policy and programs, and for engagement between central and regional teams where issues of concern to Indigenous communities could be recognised. This linkage is something that’s been lost in current decision making in my view. There is no representative voice coming up from the regions as there was when ATSIC operated. The people who worked in the bureaucracy then were also people who had experience working with Aboriginal people and who were keen to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. There were a lot of positives.

On the downside, to vote in an ATSIC election you had to be on the Australian electoral roll and a lot of Aboriginal people weren’t, and still aren’t today, unfortunately. When working at the radio station in Wilcannia, I used to encourage local Aboriginal people at election time to get on the roll, because Aboriginal advocates fought for Indigenous rights to vote. I mentioned men like Bill Ferguson and many others who fought for these rights in the 1930s and 1940s. But unless you’re on the Australian electoral roll you couldn’t vote in the ATSIC elections. Inevitably it could mean that someone might be elected with 25 votes or something ridiculous like that. So, it was imperfect in that way. I think that another disadvantage of ATSIC at times was an internal “boys’ club” operating at the top with key individuals wielding undue influence that wasn’t healthy for the Commission overall. On the other hand, there were significant female CEOs like Pat Turner and Lowitja O’Donoghue. Yet it was the downsides, which enabled John Howard to run ATSIC down in name and action and then dismember it.

I joined ATSIC in December 2004- in its dying throes. It collapsed early in 2005. I saw many of my new colleagues skedaddle to different positions outside of Canberra given they knew the fallout coming. In preparation of ATSIC’s demise, a group had been formed in the Department of Immigration and Indigenous Affairs, called the Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination, and once the machinery of government change occurred when ATSIC folded this group was brought in. Many public servants who had been working in different program areas (e.g Indigenous health or education) were moved into mainstream Health or Education Departments. A lot had terrible experiences since they were treated like pariahs because it was publicly said that ATSIC was rorting funds and that the people working for ATSIC were incompetent and spoilers, and so on. Staff who had worked in ATSIC had a very, very difficult time transitioning to their new departments.

For people working in native title, where I was working at the time, the transition wasn’t easy for them either because people from the Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination basically saw us in the same way too. This made it difficult to work productively during the transition. The National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) has not replaced the regional offices which existed under ATSIC, nor the decision-making processes with regional offices. Many Aboriginal people have lost confidence in the government. There are no formal channels for them to contribute. ATSIC might have had weaknesses but, really, the baby and the bath water were thrown out together.

Yeah, ok. That’s quite disheartening to hear about models that had a lot going for them and then just being disbanded like that. So, Julie, over the past six years, you’ve been extremely instrumental in establishing a lot of programs for supporting native title anthropologists to gain the skills that are necessary to navigate what is a very complex environment, as we’ve talked about, and I’d love to know a little bit more about what the Centre for Native Title Anthropology does and why you think it’s so important to offer these development initiatives to native title anthropologists.

The Centre for Native Title Anthropology (CNTA) has been operating for 11 years at the Australian National University and is funded by the Attorney-General’s Department under a competitive grant program. This anthropology grant program had its genesis in complaints from service providers, that one of the reasons for the backlog of claims before the court was due to insufficiently experienced anthropologists available to progress claims. The courts really wanted anthropologists at a mid-senior level who could work as expert witnesses to the court, and they wanted educative courses to help upskill anthropologists at all career stages. Earlier it was thought university courses could provide the upskilling. But as we now see, universities are not interested in these sorts of courses. In fact, as we can see, they’re paring back on anthropology courses in general. There is also a prevalent view amongst universities that only Aboriginal people should teach subjects about Indigenous people. CNTA, in a way, now fills a gap by providing an educative vehicle for native title practitioners where nothing is available at any of the universities that I’m aware of. I think CNTA plays an important educative role, it provides collaborative networks and support for practitioners to meet colleagues and talk about practical problems arising in their native title work.

So, Julie, the native title era has been influencing the lives of Aboriginal people in Australia since 1994 in very profound ways. Whether it’s achieved its goal of providing Aboriginal people with recognition or not, I mean, those outcomes exist on a spectrum across the country, but I’m interested to know how far away you think we are as a nation towards achieving genuine reconciliation with the First Peoples of this land, and what do you think is needed to get us from here to there?

Okay, there’s a couple of points to make. First, non-Indigenous people feel differently about Aboriginal issues and Aboriginal recognition across the country. For example, I think on the eastern seaboard and middle-class people are interested in Aboriginal lifeways and life stories and they support diverse forms of symbolic recognition, from a Welcome to Country, to acknowledgments on our local TV stations, flying the Aboriginal flag outside key institutions, and so on. Non-Indigenous people are keen to be involved I think; they are also keen to meet Aboriginal people even if they’re not quite sure how to do that, or to understand some of the complexities and conflicting things within this space. They value Aboriginal art. They embrace Aboriginal tourism.

In country areas, by contrast, I think the enthusiasm is not so even; for example, there are farmers finding stone tools in their paddocks some of whom value these objects and want to deposit them in museums. While others are frightened and concerned it will lead to a claim over their country. It indicates that native title is still not always understood by the general population. But I do think we’ve come a long way in my lifetime. One of the biggest steps forward, I think, were the outcomes of the Whitlam government in the mid-1970s, when Indigenous Legal Aid was implemented, along with Indigenous health services, and the Australia Council funding Indigenous art and literature. The latter led to a plethora of Aboriginal biographies. One of the first of such books I read in that period was by Bobbie Hardy – ‘The world owes me nothing’. It’s about an Aboriginal shearer in Western New South Wales describing his life and his struggles. So suddenly, the wider society had the opportunity to read about the experiences of people previously unknown to them.

So native title has made a big contribution to Aboriginal status, I think. The right to negotiate and to sit at the table with miners and developers for the first time gave Indigenous Australians the opportunity to talk about their country and raise their concerns, where before their views and feelings were overlooked or dismissed. I remember one of the first claims I worked on and during the first hour of the hearing, the group wanted to unload about the frustrations that they had when no one took them seriously, no one listened to their concerns. Moving from a point where people felt that they didn’t have a voice to say anything to a situation where they have got a right to say something and to make decisions about their country, that is important.

I think the other thing that has changed is the nomenclature around Australian Indigenous people. So you know, when I started out in Aboriginal Affairs Aboriginal people was just a cover term for everyone around Australia, then we started identifying people as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, and now we have language group names relating to countries, and more recently we use the term, First Nations. Our lens, if you like, was very generalised and now it is becoming more nuanced such that we appreciate specificities, locations, languages, and Indigenous histories, which goes again, to what came out of the land rights era. As a result of the land rights era, for the first time, historical records were compiled to chronicle the history of groups and their country, and this history was being revealed and made publicly accessible.

We’ve come a long way, a very long way. Another step forward has been accepting Aboriginal people and their cultural background rather than saying people are 1/6 this and 1/7 that. Aboriginal people now have the choice to identify or not, and to live the kind of life they want, as an Aboriginal person or as a person of Aboriginal descent. There are Indigenous people, for example, who attend university who have Aboriginal descent but don’t want to be identified in that way. Amongst artists there are some who say, “I don’t want to be called an Aboriginal artist, I just want to be called an Australian artist”. So, there are many shifts going on.

Yeah, that’s interesting Julie. So that leads me to my last question, Julie. What do you think anthropology has to offer the future of humanity?

Look, I feel very positive about that because I think anthropology gives you a set of skills, which you can use in any context. Some years ago, Professor Annette Hamilton, an early researcher in Aboriginal Australia and who wrote a fabulous book on child-rearing in the Western Desert, gave a keynote address at an Australian Anthropology Society conference. She posed a question not dissimilar to what you’ve just asked; “why aren’t anthropologists explaining more about human nature and all the permutations that arise?” “Why have historians and psychologists got the upper hand here?”

I think that’s a question that’s still very relevant today and it goes in some ways, perhaps, to something about the discipline but also to the self-selection of personalities that go into the discipline. Often anthropologists are very individualistic, even loners, given fieldwork is generally conducted alone. And I think that, in returning to our earlier discussion about applied anthropology, I remember someone who had submitted an article about applied anthropology to one of our journals and they were subsequently told that it was not written in a way sufficient for an academic audience. So, we’ve put boundaries around the way we think anthropology should engage with people without understanding that anthropology is a broad church, and we need to write for different audiences.

Peter Sutton has written two books now for a broad audience; The Politics of Suffering, and now, The Hunters and Gatherers or Farmers Debate, and we don’t do enough of that. We write for our colleagues more than we write for the wider audience, and I think, there’s going to be a problem in that, because our colleagues, as we have spoken about earlier, are becoming a smaller and smaller cohort in the academy. We know too that it can take up to two years to publish an article in an academic journal, whereas if we were writing for The Conversation, or writing a book for a general readership, we’ve got more capacity to influence through those sources than we do by sticking to an academic pathway. However, if you’re in the academy, that’s the only pathway that gets you the recognition that you need for your own advancement.

So, what does anthropology have to offer? Well, someone once said to me, it’s a calling, and if it’s a calling, then it’s something that permeates your whole orientation to the world, and how you understand your everyday life. Anthropology is not just about the exotic, it’s about anything and everything, as far as I’m concerned. And it’s interesting to use that anthropological lens on your everyday experience, you know, sitting in the doctor’s waiting room, and observing how people comport themselves there? How are decisions made? What are the power structures you can see operating here? All those kinds of concepts and observations are relevant to the way we understand our life and the lives of others. So, that would be my take.

Julie pictured in the center at ‘Ethics, Advocacy and Expertise’ event in Collingwood, September 2023

Julie pictured in the center at ‘Ethics, Advocacy and Expertise’ event in Collingwood, September 2023Want to learn more about the Centre for Native Title Anthropology? Peruse their website and resources here.

Visit the National Native Title Tribunal to learn more about native title in Australia.

Visit Julie’s Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research profile here.

@anthroprospective