Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this interview may contain images and names of deceased persons.

︎︎︎

Patrick Sullivan explores the development of Australian Aboriginal policy

Interviewer: Courtney Boag

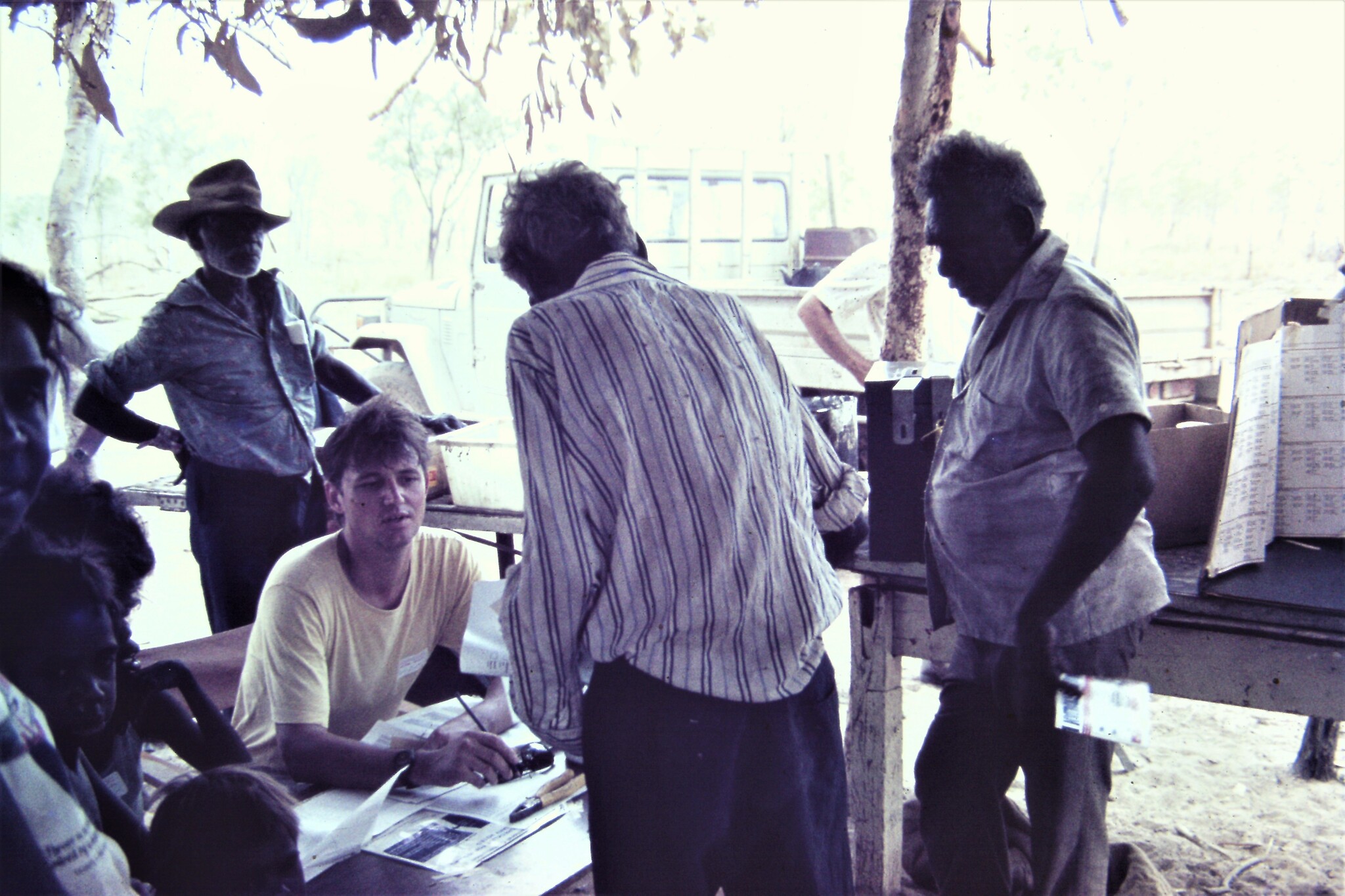

Image:Patrick on his way to the Kimberley’s with an Australian National University Landcruiser, 1983 (Photo: Patrick Sullivan)

17 February, 2023

“It’s the ability to suspend your preconceptions or your own firmly held beliefs in order to listen and understand where somebody from a fundamentally different cultural orientation is coming from because what they are trying to communicate to you is very important. An anthropological skill that we can bring to our interactions is to focus on that deep listening and encourage others to do the same”

Patrick Sullivan

Patrick Sullivan is a political anthropologist who has worked for numerous Aboriginal organisations within Australia for over four decades. He has become a leading thinker on issues relating to land use and distribution, Aboriginal policy and governance, community development, indigenous rights and the operation of Aboriginal controlled and run organisations. Patrick began his career as an anthropologist in the Kimberleys in north west Australia where he explored the impacts of the ‘inter-cultural’ space created by non-Aboriginal administrative and policy processes and bureaucratic interventions. After his PhD research, Patrick went on to become a Senior anthropologist at the Kimberley Land Council where he provided anthropological and policy advice on local, national and international projects, as well as native title cases. Between 2002 to 2012, Patrick was the Research Fellow and Senior Research Fellow, in Indigenous Regional Organisation, Governance and Public Policy at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies where he focused his research on public policy approaches to Indigenous affairs. Throughout his career, Patrick has offered advice on a number of working groups and was most notably acknowledged for his involvement in supporting Aboriginal delegates during the drafting of the United Nations Declaration of Indigenous Rights. Patrick has authored numerous publications and two well-known books entitled: All Free Man Now; Culture, Community and Politics in the Kimberley Region North Western Australia and Belonging Together: Dealing with the Politics of Disenchantment in Australian Indigenous Policy. He is currently an Honorary Professor at the Crawford School for Public Policy at the Australian National University and Professor at Nulungu Research Institute, University of Notre Dame Australia in Broome. He leads the ARC-funded project Reciprocal Accountability and Public Value in Aboriginal Organisations.

So, I just wanted to begin Patrick by asking you how you became an anthropologist.

Look, it was never really my intention to be an anthropologist. It was not really in my life plan to become an academic or an intellectual. I grew up in England in institutional care. My father died when I was young and my mother couldn't keep us, so that meant that in my early adulthood, say about the age of 18 or 19, I was just a free labourer in the labour market. I had little education as I had left formal schooling at 14 so I didn't even complete 10th grade. This was during the late 60s through to the early 70s, so there was a lot going on in terms of social movements, and that was very exciting for a young person. In terms of my progression though I didn’t feel like I had much of a career future, so I took whatever work I could and started travelling around. I had heard that you could get work in Australia easily and the money was good, so I travelled out here. But on my way, I passed through a whole lot of other countries. I’d previously travelled through Europe, spent six months working in Israel, and on the later trip passed a year in India before arriving in Australia. I suppose that was my introduction to people of other cultures, which of course I found fascinating.

So, cutting the story short, at the age of 27 I came across a handbook to Murdoch University and I found it fascinating that you could do all these different courses and learn all these different things. I was intrigued and, fortunately, Murdoch was set up in those days to encourage people like me to enter the university system. I think if it had been another university, I probably wouldn't have enrolled because it may have been too difficult to get started. So, I enrolled to do Southeast Asian studies because I had travelled through Asia and I thought, you know, in the future I might go back with a couple of languages and some background in history, culture and so on, and maybe make myself useful.

So that was my introduction to anthropology. I’d picked up some street Marxism and pop anthropology through the ‘60s, but my Murdoch teachers introduced me to rigorous critical thought that built on my self-taught background. But, after I was finished with my undergraduate and Honours year, I realised that I no longer wanted to involve myself in Southeast Asia. I'd become very much convinced by Edward Said's critique of the idea of the ‘Orient’ and ‘Orientalism’ and I thought that Asian studies were still very much enmeshed in that sort of perspective which I didn't want to be a part of. I was then, and probably still am to an extent, quite radical in terms of my political perspectives.

During this time, in say the early 1980s, I was reading in the newspapers about the eviction of Aboriginal people from pastoral stations, the encroachment of multinational mining companies into the Kimberley region and the drilling of Aboriginal sacred sites. Before I had enrolled in university, one of the many casual jobs I'd had was working for the Mount Newman Mining Company in Port Hedland driving a site delivery ute, so I'd seen the condition of Aboriginal people there and the way that they were impacted by mining and I thought, this is what's going to happen in the Kimberley. So, I thought I would use my newfound qualification to go to the Kimberley and see what I could do to help.

That’s interesting Patrick, what were your next steps?

Well, I enrolled for a PhD in Anthropology as a way of getting the funds I needed to be able to get to the Kimberley and see what was going on there, particularly in terms of mineral development. There wasn't anything much going on in the Kimberley in that regard, but there was a lot of exploration. There was only one major mine there at the time, the Argyle Diamond Mine, which was very self-contained and actually did have a formal agreement with the local Aboriginal people. Whether it was, you know, adequate or not, I’m not sure but there was an agreement in place. There was a lot of mineral exploration, though, in the dry season, and this showed me how little control Aboriginal people had over their traditional land and the preservation of their cultural sites. More broadly, and influencing me greatly until the present day, what I did find when I got to the Kimberley was that Aboriginal people were being impacted by non-indigenous administrative and policy processes and bureaucratic interventions. Ironically, from being determined not to contribute to post-colonial intervention in Asia I had landed myself in an actual colonial conflict in the north of my own state, which, rather stupidly, I’d had no idea still existed. So, I became involved in a network of Aboriginal community-controlledorganisations that were interacting with that overarching and fundamentally colonial administrative process. My idea of what it was that I wanted to do in my PhD shifted at that point. It was still anthropology, but not so much oriented towards the cultural impact of mining, but more an anthropology of contemporary governance, and political and administrative processes.

Yeah, that’s interesting and such a natural part of the research process hey, you have to be flexible. So, I understand that a lot of your early work in the Kimberleys after this explored the effects of Aboriginal people being evicted from pastoral stations. Why was this happening and what were some of the implications of this?

Well, they weren't only being pushed off pastoral stations, they were being firmly encouraged off mission stations as well. So, it was at the tail end of the assimilation era when assimilation policies were being actively pursued. Nowadays assimilation policies are hidden within other forms of policy interventions, but during this time, the state didn't see the future for Aboriginal people as being shut away from the rest of society on missions or pastoral stations, they wanted to assimilate them into wider society. So, to encourage Aboriginal people off the missions, the states were removing their subsidies, and in terms of the pastoral stations, they were turning a blind eye to evictions. The introduction of the pastoral award wage which required pastoralists to pay Aboriginal people the same rate that non-Aboriginal people were receiving for the same kind of work is one simple story that is often told as a response to why Aboriginal people were being pushed off pastoral stations. In fact, it's more complex than that. I've recently re-read the work of Fiona Skyring on this topic, and she provides a really interesting analysis of this. A lot of things were happening at the same time when Aboriginal people were leaving the stations. We were moving from an era where Aboriginal people were not free, they were not free to move from missions where they had been sent. They were not free to move from the pastoral stations where they were effectively indentured labourers. You know, if they did leave without permission, then the police would chase them down and grab them to take them back.

Pastoralists had access to large amounts of cheap labour during this time and their only obligation was to provide the very basic requirements of the native welfare departments, which was to provide, you know, tea, sugar, flour and so on, and not to treat people too harshly. But this all changed after the Second World War and Aboriginal people began taking their place as equal citizens. The pastoral industry was also changing during this time in two major ways. As Fiona points out, the state government - I'm particularly talking about Western Australia here - realised that essentially they'd been propping up an extremely inefficient system of raising cattle which was not making the best use of available land. They began to bring in much stricter lease provisions, which had the desired effect of pushing out some of the pastoralists who were not prepared to get with the modern world and bringing in those that were prepared to modernise. Part of that modernisation was that the relationships which had been formed between the old pastoralists and the Aboriginal people were broken. So, the older pastoralists left the industry, and the new pastoralists came in and they didn't have the same relationships with the local Aboriginal people, now whether those previous relationships were good or bad, I’m not sure and I would say it was probably mixed all over the country. But the new pastoralists came in and they largely didn’t want to support Aboriginal labour, they certainly didn’t want to pay them equal wages. At the same time, there were technological changes, such as moving to paddocking for cattle instead of open-range systems, and you know, open-range cattle had required a much larger workforce because you needed people on horseback to keep moving the cattle around. But with these new ways of controlling cattle in paddocks, you could get away with a much smaller workforce. There were also improvements in technology – 4WD vehicles, motorbikes, helicopter mustering, and so on.

So, you know, it wasn't just a matter of the pastoralists not wanting to pay equal wages. That was significant but it was only one part of it, it was also because the labour was just not required anymore, at least not in the same way that it had been required previously. But to answer your question about the implications of this. Well, I remember working with an Aboriginal group in the early 80s. An important tradition at the end of the mustering season was for everyone to head into town for a big party. In Halls Creek that was the annual race. I remember that the people I was working with from this particular station, Gordon Downs, told me they were brought into the races and told not to return to work. Then a group of them decided to go back to the station to see what the issue was, and the manager shot their dogs and confronted them with his rifle. The threat was, this is what will happen to you if you don’t go back to town. I was working in Halls Creek a couple of years after this and at the time when the last of the workers were forced like that off Sturt Creek Station and Nicholson Station, for example. So, a lot of people ended up going into small northern towns close to their traditional lands and their historical station communities, towns like Tennant Creek, Katherine, Halls Creek or Fitzroy Crossing to go and live in overcrowded camps.

Look, it was never really my intention to be an anthropologist. It was not really in my life plan to become an academic or an intellectual. I grew up in England in institutional care. My father died when I was young and my mother couldn't keep us, so that meant that in my early adulthood, say about the age of 18 or 19, I was just a free labourer in the labour market. I had little education as I had left formal schooling at 14 so I didn't even complete 10th grade. This was during the late 60s through to the early 70s, so there was a lot going on in terms of social movements, and that was very exciting for a young person. In terms of my progression though I didn’t feel like I had much of a career future, so I took whatever work I could and started travelling around. I had heard that you could get work in Australia easily and the money was good, so I travelled out here. But on my way, I passed through a whole lot of other countries. I’d previously travelled through Europe, spent six months working in Israel, and on the later trip passed a year in India before arriving in Australia. I suppose that was my introduction to people of other cultures, which of course I found fascinating.

So, cutting the story short, at the age of 27 I came across a handbook to Murdoch University and I found it fascinating that you could do all these different courses and learn all these different things. I was intrigued and, fortunately, Murdoch was set up in those days to encourage people like me to enter the university system. I think if it had been another university, I probably wouldn't have enrolled because it may have been too difficult to get started. So, I enrolled to do Southeast Asian studies because I had travelled through Asia and I thought, you know, in the future I might go back with a couple of languages and some background in history, culture and so on, and maybe make myself useful.

So that was my introduction to anthropology. I’d picked up some street Marxism and pop anthropology through the ‘60s, but my Murdoch teachers introduced me to rigorous critical thought that built on my self-taught background. But, after I was finished with my undergraduate and Honours year, I realised that I no longer wanted to involve myself in Southeast Asia. I'd become very much convinced by Edward Said's critique of the idea of the ‘Orient’ and ‘Orientalism’ and I thought that Asian studies were still very much enmeshed in that sort of perspective which I didn't want to be a part of. I was then, and probably still am to an extent, quite radical in terms of my political perspectives.

During this time, in say the early 1980s, I was reading in the newspapers about the eviction of Aboriginal people from pastoral stations, the encroachment of multinational mining companies into the Kimberley region and the drilling of Aboriginal sacred sites. Before I had enrolled in university, one of the many casual jobs I'd had was working for the Mount Newman Mining Company in Port Hedland driving a site delivery ute, so I'd seen the condition of Aboriginal people there and the way that they were impacted by mining and I thought, this is what's going to happen in the Kimberley. So, I thought I would use my newfound qualification to go to the Kimberley and see what I could do to help.

That’s interesting Patrick, what were your next steps?

Well, I enrolled for a PhD in Anthropology as a way of getting the funds I needed to be able to get to the Kimberley and see what was going on there, particularly in terms of mineral development. There wasn't anything much going on in the Kimberley in that regard, but there was a lot of exploration. There was only one major mine there at the time, the Argyle Diamond Mine, which was very self-contained and actually did have a formal agreement with the local Aboriginal people. Whether it was, you know, adequate or not, I’m not sure but there was an agreement in place. There was a lot of mineral exploration, though, in the dry season, and this showed me how little control Aboriginal people had over their traditional land and the preservation of their cultural sites. More broadly, and influencing me greatly until the present day, what I did find when I got to the Kimberley was that Aboriginal people were being impacted by non-indigenous administrative and policy processes and bureaucratic interventions. Ironically, from being determined not to contribute to post-colonial intervention in Asia I had landed myself in an actual colonial conflict in the north of my own state, which, rather stupidly, I’d had no idea still existed. So, I became involved in a network of Aboriginal community-controlledorganisations that were interacting with that overarching and fundamentally colonial administrative process. My idea of what it was that I wanted to do in my PhD shifted at that point. It was still anthropology, but not so much oriented towards the cultural impact of mining, but more an anthropology of contemporary governance, and political and administrative processes.

Yeah, that’s interesting and such a natural part of the research process hey, you have to be flexible. So, I understand that a lot of your early work in the Kimberleys after this explored the effects of Aboriginal people being evicted from pastoral stations. Why was this happening and what were some of the implications of this?

Well, they weren't only being pushed off pastoral stations, they were being firmly encouraged off mission stations as well. So, it was at the tail end of the assimilation era when assimilation policies were being actively pursued. Nowadays assimilation policies are hidden within other forms of policy interventions, but during this time, the state didn't see the future for Aboriginal people as being shut away from the rest of society on missions or pastoral stations, they wanted to assimilate them into wider society. So, to encourage Aboriginal people off the missions, the states were removing their subsidies, and in terms of the pastoral stations, they were turning a blind eye to evictions. The introduction of the pastoral award wage which required pastoralists to pay Aboriginal people the same rate that non-Aboriginal people were receiving for the same kind of work is one simple story that is often told as a response to why Aboriginal people were being pushed off pastoral stations. In fact, it's more complex than that. I've recently re-read the work of Fiona Skyring on this topic, and she provides a really interesting analysis of this. A lot of things were happening at the same time when Aboriginal people were leaving the stations. We were moving from an era where Aboriginal people were not free, they were not free to move from missions where they had been sent. They were not free to move from the pastoral stations where they were effectively indentured labourers. You know, if they did leave without permission, then the police would chase them down and grab them to take them back.

Pastoralists had access to large amounts of cheap labour during this time and their only obligation was to provide the very basic requirements of the native welfare departments, which was to provide, you know, tea, sugar, flour and so on, and not to treat people too harshly. But this all changed after the Second World War and Aboriginal people began taking their place as equal citizens. The pastoral industry was also changing during this time in two major ways. As Fiona points out, the state government - I'm particularly talking about Western Australia here - realised that essentially they'd been propping up an extremely inefficient system of raising cattle which was not making the best use of available land. They began to bring in much stricter lease provisions, which had the desired effect of pushing out some of the pastoralists who were not prepared to get with the modern world and bringing in those that were prepared to modernise. Part of that modernisation was that the relationships which had been formed between the old pastoralists and the Aboriginal people were broken. So, the older pastoralists left the industry, and the new pastoralists came in and they didn't have the same relationships with the local Aboriginal people, now whether those previous relationships were good or bad, I’m not sure and I would say it was probably mixed all over the country. But the new pastoralists came in and they largely didn’t want to support Aboriginal labour, they certainly didn’t want to pay them equal wages. At the same time, there were technological changes, such as moving to paddocking for cattle instead of open-range systems, and you know, open-range cattle had required a much larger workforce because you needed people on horseback to keep moving the cattle around. But with these new ways of controlling cattle in paddocks, you could get away with a much smaller workforce. There were also improvements in technology – 4WD vehicles, motorbikes, helicopter mustering, and so on.

So, you know, it wasn't just a matter of the pastoralists not wanting to pay equal wages. That was significant but it was only one part of it, it was also because the labour was just not required anymore, at least not in the same way that it had been required previously. But to answer your question about the implications of this. Well, I remember working with an Aboriginal group in the early 80s. An important tradition at the end of the mustering season was for everyone to head into town for a big party. In Halls Creek that was the annual race. I remember that the people I was working with from this particular station, Gordon Downs, told me they were brought into the races and told not to return to work. Then a group of them decided to go back to the station to see what the issue was, and the manager shot their dogs and confronted them with his rifle. The threat was, this is what will happen to you if you don’t go back to town. I was working in Halls Creek a couple of years after this and at the time when the last of the workers were forced like that off Sturt Creek Station and Nicholson Station, for example. So, a lot of people ended up going into small northern towns close to their traditional lands and their historical station communities, towns like Tennant Creek, Katherine, Halls Creek or Fitzroy Crossing to go and live in overcrowded camps.

Two Sturt Creek pensioners arrive to set up an outsation, 1983

(Photo: Patrick Sullivan)

(Photo: Patrick Sullivan)

Yagyiarri Jack Huddlestone sets up his first outsation post Seaman Flora Valley, 1986 (Photo: Patrick Sullivan)

Yeah right, so there was a whole range of things happening at once, impacts that were influenced by the changing times as well.

Yeah, that’s it, it’s not as simple as to say that it was simply one element that was solely responsible for this change, no it was complex.

Well, that’s it isn’t it, these things are rarely the result of one contributing factor, there’s usually more to the story. So, I understand that a lot of your work since then has explored the developments of Aboriginal policy in the post-war era. Can I start by asking you what is so important about this historical event, the ‘post-war era’ with regards to Aboriginal policy here in Australia?

Well, I think one of the important things is posing the question in that way. I do try to make the point in my writings that we have a tendency in Australia to kind of look at ourselves as if the rest of the world doesn't exist. As if we aren’t part of international movements and processes. Whatever happens here is, you know, entirely under our control. That is amplified in terms of Aboriginal discourse, I think, both in Aboriginal policy and especially among Aboriginal people themselves. There is, of course, good reasons for a discourse of indigenous exceptionalism, indigenous people are different, indigenous people have unique rights and so on, but I tend to want to raise a voice against that only because it is such a dominating discourse. It’s also true that what happens in Indigenous affairs is the result of what is happening in Australian society more broadly, which is very much influenced by what is happening with international movements, whether we are aware of that or not. So, I think that if we don't accept that, then Indigenous people themselves cannot analyse the situation that they're in with all of the necessary information and therefore see what it is they're up against and what might be the best thing to do about it. So, that's one of the reasons that I look at things in broad periods and events that have occurred around the world, particularly in recent history. I find it useful to look at the effects on Australian policy and conditions of two major social, economic and political movements since the end of the Second World War. The first of these is a complex mix of the rise of the ‘Welfare State’, the process of international decolonisation, and more broadly, various forms of social progressivism particularly in the late 60s and early 70s. The second big post-war movement is the backlash to this, the counter-revolution of neo-liberalism as a political, economic, social and bureaucratic force personified by the figureheads of the UK’s PM Thatcher and the US’s President Reagan.

Australia was impacted by these events and inevitably Australian Indigenous policy and Australian Indigenous peoples were impacted. In 1967, at the height of the socially progressive post-war period of decolonisation worldwide, we had the referendum that gave power to the Commonwealth to make laws for Aboriginal people. One of the motivating factors behind it was that it would allow the Commonwealth government to deal with the embarrassment - the international embarrassment – of maintaining a colonial relationship with its Indigenous people. I mean, let us make that clear, it was obvious that Aboriginal people were not free citizens in Australia. So, on the one hand, the people’s movement behind the 67’ referendum was also part of a worldwide movement of socially progressive agitation, if you like, and land rights were one aspect of that. The anti-Vietnam war and the anti-apartheid movement were also part of this larger global movement. This made it politically imperative for Australia to complete the formal, jural, liberation and enfranchisement of its Indigenous peoples, and to support the development of Aboriginal community-controlled organisations as a limited and controlled form of self-determination. It was a time of great revolution and turmoil right throughout the world. Then we witnessed the counter-revolution of the rise of neoliberalism in the early to mid-80s.

The changes in government policy during that time in Australia also particularly affected Aboriginal people. I think one thing that would resonate with most Aboriginal people is the abolition of the Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander Commission. The establishment of ATSIC in 1989/1990 was the result of some 50 years of post-war enthusiasm for decolonisation and it was Australia’s attempt at a decolonisation measure. It was certainly expressed in those terms in international forums at the United Nations, you know, that ATSIC is Australia's answer to the need for Aboriginal Self-Determination. However, the abolition of ATSIC in 2005 signalled the imposition of neoliberal, market-oriented policies and new public management approaches in the bureaucracy that have impacted Aboriginal people very seriously ever since. So, those are the reasons that I refer to the ‘post-war period’, I mean it’s a fairly artificial timeframe but it’s a very convenient point to say, well, you know, how did policy develop among most of the developed states? Then how did it change? And where are we today?

It's an interesting point, I mean, it’s important to acknowledge that it has been somewhat of a messy journey towards Self-Determination for Aboriginal people in Australia. Patrick, throughout your career as an anthropologist working in this space, have you seen any kind of overarching agenda for how we go forward with reconciliation, or do you think these policies have been somewhat ad hoc?

Well, ad hoc policies tend to coalesce over a period into something that you can then say, this actually is a policy we can put a name to. So yes, it's ad hoc, but yes, there are underlying consistencies that, you know, we can then say, particularly with hindsight, we say, ‘oh look, yeah, that was this or that policy’. I think particularly in Aboriginal affairs here in Australia we have had policy movements that can be characterised in certain terms, you know, there was the ‘protection’ era with all its paternalistic segregation policies, then there was the ‘assimilation’ era with various policies for assimilation and now we have this discourse around ‘Self-Determination’. While there’s rarely a big picture statement from politicians for any of this, policy analysts and historians will look back and say, ‘oh, yes, but there was a policy even though it seemed to be rolled out in a very ad hoc manner’. I think the big picture policy since, particularly the end of the Second World War, has been assimilation. That is the underlying theme of all policies. Even through the ATSIC era, for instance. Now we are talking about Treaty; a national Treaty and state Treaties and we can talk about that in a few minutes, but even these Treaties, as they are presently conceived, are a way of binding Aboriginal people into the mainstream polity. Therefore, in that sense, part of an assimilation framework. So, I think there's always underlying policy, but I think it's not always evident. Sometimes it's not evident until several years later when you can look back on it.

You know there was an old saying when I was growing up about fortune tellers who would read the tea leaves at the bottom of the cup, and guessing what powerful people were up to was ‘trying to read the tea leaves at the bottom of the cup’. I don’t know if you're familiar with that saying, but it’s a bit like that, you know trying to understand what contemporary policy is, well it's rather like trying to read the tea leaves. You have to take a whole range of government policy documents and pick out recurring phrases to understand the underlying philosophy. But you know, sometimes policy is deliberately obscure. Sometimes it's just a matter of that's the way policy rolls out. Because of the need to satisfy conflicting forces that contribute to policy formulation the result often just is ambiguous.

Yeah, that’s it, it’s not as simple as to say that it was simply one element that was solely responsible for this change, no it was complex.

Well, that’s it isn’t it, these things are rarely the result of one contributing factor, there’s usually more to the story. So, I understand that a lot of your work since then has explored the developments of Aboriginal policy in the post-war era. Can I start by asking you what is so important about this historical event, the ‘post-war era’ with regards to Aboriginal policy here in Australia?

Well, I think one of the important things is posing the question in that way. I do try to make the point in my writings that we have a tendency in Australia to kind of look at ourselves as if the rest of the world doesn't exist. As if we aren’t part of international movements and processes. Whatever happens here is, you know, entirely under our control. That is amplified in terms of Aboriginal discourse, I think, both in Aboriginal policy and especially among Aboriginal people themselves. There is, of course, good reasons for a discourse of indigenous exceptionalism, indigenous people are different, indigenous people have unique rights and so on, but I tend to want to raise a voice against that only because it is such a dominating discourse. It’s also true that what happens in Indigenous affairs is the result of what is happening in Australian society more broadly, which is very much influenced by what is happening with international movements, whether we are aware of that or not. So, I think that if we don't accept that, then Indigenous people themselves cannot analyse the situation that they're in with all of the necessary information and therefore see what it is they're up against and what might be the best thing to do about it. So, that's one of the reasons that I look at things in broad periods and events that have occurred around the world, particularly in recent history. I find it useful to look at the effects on Australian policy and conditions of two major social, economic and political movements since the end of the Second World War. The first of these is a complex mix of the rise of the ‘Welfare State’, the process of international decolonisation, and more broadly, various forms of social progressivism particularly in the late 60s and early 70s. The second big post-war movement is the backlash to this, the counter-revolution of neo-liberalism as a political, economic, social and bureaucratic force personified by the figureheads of the UK’s PM Thatcher and the US’s President Reagan.

Australia was impacted by these events and inevitably Australian Indigenous policy and Australian Indigenous peoples were impacted. In 1967, at the height of the socially progressive post-war period of decolonisation worldwide, we had the referendum that gave power to the Commonwealth to make laws for Aboriginal people. One of the motivating factors behind it was that it would allow the Commonwealth government to deal with the embarrassment - the international embarrassment – of maintaining a colonial relationship with its Indigenous people. I mean, let us make that clear, it was obvious that Aboriginal people were not free citizens in Australia. So, on the one hand, the people’s movement behind the 67’ referendum was also part of a worldwide movement of socially progressive agitation, if you like, and land rights were one aspect of that. The anti-Vietnam war and the anti-apartheid movement were also part of this larger global movement. This made it politically imperative for Australia to complete the formal, jural, liberation and enfranchisement of its Indigenous peoples, and to support the development of Aboriginal community-controlled organisations as a limited and controlled form of self-determination. It was a time of great revolution and turmoil right throughout the world. Then we witnessed the counter-revolution of the rise of neoliberalism in the early to mid-80s.

The changes in government policy during that time in Australia also particularly affected Aboriginal people. I think one thing that would resonate with most Aboriginal people is the abolition of the Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander Commission. The establishment of ATSIC in 1989/1990 was the result of some 50 years of post-war enthusiasm for decolonisation and it was Australia’s attempt at a decolonisation measure. It was certainly expressed in those terms in international forums at the United Nations, you know, that ATSIC is Australia's answer to the need for Aboriginal Self-Determination. However, the abolition of ATSIC in 2005 signalled the imposition of neoliberal, market-oriented policies and new public management approaches in the bureaucracy that have impacted Aboriginal people very seriously ever since. So, those are the reasons that I refer to the ‘post-war period’, I mean it’s a fairly artificial timeframe but it’s a very convenient point to say, well, you know, how did policy develop among most of the developed states? Then how did it change? And where are we today?

It's an interesting point, I mean, it’s important to acknowledge that it has been somewhat of a messy journey towards Self-Determination for Aboriginal people in Australia. Patrick, throughout your career as an anthropologist working in this space, have you seen any kind of overarching agenda for how we go forward with reconciliation, or do you think these policies have been somewhat ad hoc?

Well, ad hoc policies tend to coalesce over a period into something that you can then say, this actually is a policy we can put a name to. So yes, it's ad hoc, but yes, there are underlying consistencies that, you know, we can then say, particularly with hindsight, we say, ‘oh look, yeah, that was this or that policy’. I think particularly in Aboriginal affairs here in Australia we have had policy movements that can be characterised in certain terms, you know, there was the ‘protection’ era with all its paternalistic segregation policies, then there was the ‘assimilation’ era with various policies for assimilation and now we have this discourse around ‘Self-Determination’. While there’s rarely a big picture statement from politicians for any of this, policy analysts and historians will look back and say, ‘oh, yes, but there was a policy even though it seemed to be rolled out in a very ad hoc manner’. I think the big picture policy since, particularly the end of the Second World War, has been assimilation. That is the underlying theme of all policies. Even through the ATSIC era, for instance. Now we are talking about Treaty; a national Treaty and state Treaties and we can talk about that in a few minutes, but even these Treaties, as they are presently conceived, are a way of binding Aboriginal people into the mainstream polity. Therefore, in that sense, part of an assimilation framework. So, I think there's always underlying policy, but I think it's not always evident. Sometimes it's not evident until several years later when you can look back on it.

You know there was an old saying when I was growing up about fortune tellers who would read the tea leaves at the bottom of the cup, and guessing what powerful people were up to was ‘trying to read the tea leaves at the bottom of the cup’. I don’t know if you're familiar with that saying, but it’s a bit like that, you know trying to understand what contemporary policy is, well it's rather like trying to read the tea leaves. You have to take a whole range of government policy documents and pick out recurring phrases to understand the underlying philosophy. But you know, sometimes policy is deliberately obscure. Sometimes it's just a matter of that's the way policy rolls out. Because of the need to satisfy conflicting forces that contribute to policy formulation the result often just is ambiguous.

Patrick on the polling booth for the 1984 election Mt Elizabeth station community (Photo: Tom Stevens MLC)

I was reading The Saturday Paper recently and it was explaining that support for an Aboriginal Treaty in Australia is declining, so I wanted to ask you, do you think policymakers, politicians, lawyers etcetera need to do a better job of communicating these policies to the general public?

Yeah, well there's a big debate going on at the moment and I'm only on the periphery of it and I'm not Aboriginal so, I would not want to take sides. But it's a debate about the sequence. We are looking at say at least three elements. One is a representative Voice that is enshrined in the Constitution. Secondly, we're looking at a truth-telling commission and then thirdly, we are looking at a Treaty or smaller state-based Treaties. All of these things are on the political agenda. Sequencing is a matter of great debate among Aboriginal people. Some people think Treaty should come first and out of the Treaty will come to a Voice. There's great fear that if a Voice is set up first it will be a weak voice, and if it then has the power of negotiating a Treaty it may be a weak Treaty because it would be under the thumb of the government. Consequently, any sort of truth-telling commission may go down the same path as the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, for instance, or the ‘Bringing them Home’ report on the Stolen Generations and so on. That is, referred to reverentially but mostly ignored. So, there are very clear and real fears there on the Aboriginal side that are grounded in lived experience. My feeling for what it's worth is that I would've thought a truth-telling commission that worked well could be the basis for bringing to the attention of the Australian people the need for a strong Voice in Australia, and the need for a strong Treaty. But I may be being naive about that.

But your question was about whether we should do a better job of communicating with the general public. And I do think we, the professionals and the scholars, are failing in that regard. For example, I admire the work of Asmi Wood at the Australian National University, and it should get much greater currency. He is a scholar in international law and he's a Torres Strait Islander person himself. But his ideas haven’t got much currency in wider discourse so far. He makes a point in his papers that these Treaty agreements are inevitably going to be abrogated by the signatories because that's the experience everywhere else in the world, in Canada and the US for example. In New Zealand, they are either completely ignored, overturned, or they're reinterpreted and end up not meeting Indigenous objectives. I think the empirical evidence of historical experience that Asmi refers to is supported more broadly by colonialist critiques such as Franz Fanon’s and even by 1980s feminist scholars in their identification of structures of pervasive patriarchy. In a short phrase, there can be no impartial domestic remedies against entrenched power structures – they are self-perpetuating. So Asmi proposes that an Australian Indigenous treaty must be auspiced by an International rights body such as an arm of the United Nations or an International court. This would allow for an impartial arbitrator both in negotiating the terms of a treaty and also in having an unbiased forum for complaint if the spirit or the terms of the treaty are not upheld.

I tend to agree with Asmi's analysis there. I mean while I think, as many people do, that Australia badly needs a Treaty, we do need to think about how that Treaty is to be negotiated and implemented. We don't need to spend that much time at the moment, and Asmi also makes this point, in talking about what needs to go into the Treaty. It can be quite a high level establishing fundamental principles for now. Once it's established, detail can be worked out and indeed changed from time to time as the circumstances change. If you stand by the principles of the treaty, the way it works itself out can be malleable, and the actual operation of it can develop over time. All people of goodwill and common sense can understand when principles have been met and when they haven’t. But we do need to establish what are those principles and how are they to be guaranteed. One way to do that is, as Asmi says, under the auspices of an international standard-setting body such as the Special Committee on Decolonisation of the United Nations. This committee still exists and still has operational powers. So, whether it is something like that or something like the International Court of Justice, it also needs to be firmly integrated with the Universal Declaration of Indigenous Rights.

I wanted to ask you about your involvement in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Indigenous Rights. But before going into that, I just wanted to make a point that Indigenous Land Use Agreements or ILUA’s as they are also called are kind of like small Treaties that are in operation already all over the country. So, I think the general population, they don't understand that there's already an infrastructure for agreements between Aboriginal groups and State and Federal governments here in Australia. So, do you feel that there's a lot more that needs to be done to communicate what a Treaty is, and how it would operate to the general community? Do you think that there is mistrust from society towards Treaty because they simply just do not understand it and how it will be implemented?

Yeah, I think there's a big problem there in that if you, just to put it boldly, if on the one hand, you pursue a weak solution you can get a general Australian agreement. If you pursue a strong solution, then you frighten the horses. I think that there's a tendency here towards incrementalism where the government will push for something that is not particularly radical with the idea that they might be able to entrench it and build on it sometime in the future. But it’s hard to say what might happen.

I find this topic so interesting, you know, the discussion of how we can communicate complexity in more simple terms, of course without losing the substance and nuance of the topic along the way. So, I wanted to ask you, given you have now worked in this space for many decades, how can complex ideas, in whatever form, whether we're talking about Treaty or if we're talking more broadly about other social issues, how do you think they could be more effectively communicated to the general public? Do you think it's possible to do that without creating further divisions within society or do you think that information is inevitably going to be digested in different ways, thereby creating social divisions in some way regardless?

Well, yes, I think conflict is inevitable. But that doesn't mean it needs to get out of hand. You know, conflict is a necessary and constant part of life, and we shouldn't always shy away from conflict, but it needs to be managed of course. It is a difficult question because I think most people don't realise how complex Aboriginal policy is, they don't know the ins and outs of history, for example. You know, even myself, I'm still finding out things that historians are uncovering that I was unaware of. But most people, even those that have made an effort to know something about Aboriginal culture and something about Aboriginal history, don't understand everything about how Aboriginal policy is developed, how it is run out and what impact it's having on Aboriginal people today. They don't recognise the complexity of it unless they're enmeshed in it. Bureaucrats for instance, do they actually realise how multi-dimensional Aboriginal policy is? I’m not sure.

So, to try and answer your question about how to communicate to the public, well I think it’s important to make the point that, you know, it's not simple. I don't think it's any less complex than, for instance, international relations or whatever. Most people don't know very much about how their own society works, let alone how another society works, and furthermore, about how the two interact. I do think most people have a very vague idea of who empties their garbage bins, for example. You know, they put them out and they come back empty. They have a vague idea who's looking after it, but they're not too concerned about the process unless there's a problem. I don't think the general population know very much about how politics works or what policies are, and I don't think they want to, you know, people are busy with their own lives. People really only want the big picture. That sounds very sort of contemptuous of everyday people and I don't mean to be contemptuous, I'm just trying to say, in my observation, most people are not really interested in politics.

Nevertheless, we can’t give up on communicating just because at first people don’t seem very interested or think it isn’t very relevant to their lives. But it does mean we have to accept a measure of imperfection in the way we communicate. If we want to get through to people we can’t be so academically rigorous that ordinary people can’t understand what we are saying and in any case, they are bored out of their minds. Despite criticism from our academic colleagues we have to communicate sophisticated information in a somewhat unsophisticated way – ways that are more accessible to people. I think if we can do that then it’s pretty good.

Yagyiari Jack Huddlestone waiting to testify to the Seaman Inquiry Banjo Bore Halls Creek, 1984 (Photo:Patrick Sullivan)

As you’re speaking Patrick, I’m thinking about the training we get in anthropology, you know, we are trained to interrogate a question or issue from numerous perspectives and we become pretty good at being very critical of all sides of a story. So, we seldom take one side on any particular issue. Although this is something I'm seeing less and less of in society today. Rather, I’m seeing messages being communicated in very strong ways with very strong undertones from which people are kind of made to take a side on the issue rather than keeping an open mind. Do you think anthropology may have a role to play in helping this translation space at all? You know, to allow messages to be communicated with more nuance?

Possibly anthropology, but perhaps more ethnography. Because to be a good ethnographer, you need to listen and you need to put yourself in abeyance in many ways. One thing you have to learn is to just shut up, which is hard for white people to do. The other is to be more aware of your own preconceptions so that you can focus on actually listening to people and observing non-verbal cues as well from the people that you are trying to understand. So, in that sense, if we could as anthropologists and ethnographers, encourage other non-Indigenous people to listen, that would be good. But as you said, the other role that we have is to explain and interpret. That is what anthropology does.

There’s a lot that has been written on this about how we represent things which put forward the idea that when we're dealing with representations, we're not dealing with the actual thing in itself as early anthropologists believed. You know, they were being very scientific about observing something and then explaining a real thing in the real world. There was a push against that in the 80s. So, we are interpreters and we interpret to other anthropologists and academics and we interpret through academic journals - much of which is impenetrable to the everyday person. Unfortunately, that's the way universities have developed. Well, I say unfortunately, I mean, they're good for developing terms of art for highly complex subjects that are only properly understood by specialists and there's a place for that, sure, but I think it's gone too far. It's gone to the extent where we are encouraged to pay attention to that aspect of our work and not to the communication of our work. Let's put it like this, we perform for the people who immediately pay our wages and we forget the people who pay them, the citizens who pay the universities to pay our wages.

So, I think as anthropologists, our job is to, first of all, listen and then interpret and explain. Now, the other point we have to get through is that, when we are in a colonial situation as we are, we have to be very careful about the kind of explaining we do because what you are then doing is entering into the same forum, or the same area of political discourse as Aboriginal people themselves. You're not Aboriginal and the outcome is not going to affect you in the same way that it would affect an Aboriginal person. There are levels of transgression there from simply being in that space, and there’s a threat here that we can be dismissive of Aboriginal people and their voices by speaking for them. This causes more harm to Aboriginal people, or to anyone that you try to speak for because it espouses a view that if taken up or misinterpreted by bureaucrats and politicians could disadvantage those people. So, it's not a simple matter of saying, ‘oh, we're anthropologists, we understand and we'll go out and tell everybody what it's really like and we'll have to keep it simple because they don't understand very much’. No, it's highly political and there are consequences for what we do.

So I understand that you were involved in contributing to the United Nations Declaration of Indigenous Rights. I wanted to ask you about how you became involved in that process and what your experience of that process was. I mean we've been discussing this overarching concept of how you negotiate complexity and simplicity, and I'm sure you would've been face-to-face with a lot of those conundrums when you were involved in this process. So, I’d love to learn a little bit more about it.

Yeah, it was a very useful learning experience for me to see how indigenous people from all over the world organise themselves, express themselves, and how they pursue very large-scale political agendas. To be part of that was a real privilege. To see how the United Nations works and to observe the political struggles between colonised people and the colonisers in action in a forum, face-to-face, was fascinating. I came to be involved in this process for personal reasons. I submitted my PhD around the time that my son was born, and his mother is French so she wanted to return to her home country so we took him to France when he was young. His mother is from a town situated around the border between Switzerland and Geneva. So, I was wandering around the centre of Geneva one day when my boy was just a little infant and we ran into a whole bunch of Aboriginal people from Central and Northern Australia who were involved in an indigenous people's Working Group through the United Nations, I learned about that process for them when I was there. However, for personal reasons, I had to return to Australia, but my son ended up growing up in France so for many years after that I travelled back and forth to Europe. But, you know, when I was in Europe I needed to work so I thought well one way that I could work would be to go to the United Nations and try to work for indigenous people there.

I started out working voluntarily for Australian Aboriginal delegations when they attended the UN Working Group on Indigenous Peoples and ended up getting contracted in later years to delegations. My role was very simple. I sometimes had to explain a bit about how the UN worked but mostly I was just a transcriber of Aboriginal delegates' views to be put into an appropriate form for what was called an ‘intervention’ in the forum. This role allowed me to draw on my ethnographic training, because many of these people had come from bush communities or remote towns and, while they spoke English to some degree, it was really important to get their messages across as clearly as possible. So, I’d sit down with them and say well, what is it you want to say? So, I’d record their responses in a way that was halfway between something that was generally coming from their mouths, you know, it wouldn't be language that they would never use, but it also needed to be clear enough that it could be used on record for the working group on indigenous populations. When I’d been turning up often enough, and perhaps because of my work with Aboriginal representative organisations back home, I was later allowed to participate in back-room or late-night strategy discussions, always revolving around the drafting of a statement on an important aspect of the Declaration. I was very proud to work closely with the Human Rights Commission’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Mick Dodson, on these occasions.

There was one memory I had during this experience when I was there with Peter Yu who was the CEO of the Kimberly Land Council at that time. We'd just come from petitioning the Queen in London to intervene in the republic debate back in the late 90s. We wanted her to agree that she should not give her blessing to the unilateral declaration of a republic in Australia unless there was a just settlement with ‘the natives’ that her forebears had colonised. Then we went to Geneva to do the Working Group. Peter insisted that two of the old people should come with us to politically and culturally authorise the trip that we were on. At the time, we were debating the right of indigenous people to speak their own languages. In the process of making that point, one of the Aboriginal elders who were with us, Joe Brown from Fitzroy Crossing, decided to address the forum in the Walmajarri language, his language. So, he started talking to this forum, which was made up of about 100 people, most of them international diplomats, as well as indigenous people from various countries. He addressed the audience in a very clear voice all the while shaking his finger at them, he had something important on his mind that he wanted to say. He kept going like this for a long while, maybe twenty minutes. It was clear that he had something really important to say here. Only one other person in the room could understand what he was saying, the other senior Aboriginal man, John Watson. But you know, the transcribers couldn’t transcribe what Joe was saying, they tried but they couldn’t get an accurate translation, so the interpreters gave up. But you know what, by not speaking in their language – the English language, or another colonial language - and by not adhering to their protocols, he made a stronger point, one I don’t believe he could have made otherwise. It was very impressive for these sophisticated diplomats used to arguing the point to be brought up face to face with an old man from Fitzroy Crossing who had his views.

Patrick in the Kimberleys in 2016

(Photo: Julie Lahn)

(Photo: Julie Lahn)

Patrick (second from left) with Tim Goodwin (left), Mick Dodson (middle) and Asmi Wood (right) at Native Nations Institute Arizona, 2012.

(Photo:Stephen Cornell)

(Photo:Stephen Cornell)

What an amazing experience, I would have loved to be in that room. So, in your opinion, what's the importance of legislation like the Universal Declaration of Indigenous Rights? And what influence and impact does it have on Aboriginal people here in Australia? Do you think it has achieved the positive impact that it set out to achieve?

Not yet. But Aboriginal people are very patient. I'm now working with the third generation of Aboriginal people with whom I started my early work, and these young adults whose grandparents established the Aboriginal community-controlled organisations that they are now running are great. You know, it took about 10 or 15 years to get the draft Declaration through to the General Assembly and for it to be passed by the General Assembly, so it may take about that long for it to have any real effect. But you know, I remember that the United Nations was willing to give up long before the indigenous people were going to give up. I was warned by a UN bureaucrat that the process was taking too long, and the UN wanted to shut it off to a side committee to die. But the same indigenous delegates came back year after year to pick up where they’d left off. So that is a testament to their determination.

But in answer to your question, I do think it has very little effect. There is a mechanism for reporting to the UN on the progress of the Declaration in member states, but I don't think anybody knows what it is. I looked into this one day out of curiosity to see what Australia was reporting on and how they were implementing the recommendations of the Declaration. But what I found was pretty basic, they essentially said that ‘we have introduced legislation in the Northern Territory called the Stronger Futures Package’, which was quite draconian legislation that many Aboriginal Territorians disagreed with. That was the Australian Government's example of compliance and, you know, they could get away with that because nobody was keeping up with it. All the UN does is say, ‘thank you very much’ and then they move on to the next country. So, until that reporting process becomes more robust, we won't see much change. But the Declaration is not going to change, it’s not going to go anywhere so at least we have that.

One of the things that I would say about the draft Declaration, is that a lot of the debate and the stumbling point was over Article 3 on the right to Self-Determination. We said that indigenous peoples have the right to Self-Determination and there was a lot of debate over the term ‘Peoples’. Government parties were insisting that it was ‘people’ because ‘Peoples’ is a recognisable sovereign group in terms of other international instruments, you know, it was the ‘Peoples’ that were decolonised into what are now decolonised states, for example, throughout Africa. But recognising that indigenous people were not indigenous people, but were indigenous ‘Peoples’, was a real sticking point over several years of meetings. That was only the start of it because then they said, well, ‘Self-Determination’, everybody in Australia is ‘self-determining’ because we all vote - we're enfranchised citizens. But it became a bit ridiculous because the articles that received the most debate and attention seemed to have the least immediate practical impact. For example, Article 19 which recognises that Aboriginal people have the right to ‘free, prior and informed consent’ over any state decisions that affect them is much more far-reaching, but this received a lot less attention than Article 3. I think we'll see that implementing this Article will be the greatest challenge for states such as Australia.

The working group on indigenous peoples also gave indigenous people an international forum where they could embarrass their governments. I mean, it had an immediate purpose in that regard. You could go out there and say whatever was happening, so people started discussing what was happening with the Northern Territory intervention. Well, the whole world heard about this, they said this is disgusting, we're horrified. The other thing that came out of negotiating the Declaration was the experience of bringing large numbers of indigenous people together to discuss common issues and to get training on how to effectively be an indigenous politician. Many people who were involved in that process went on to become really effective people in their own countries and found themselves embedded in political processes back home.

Yeah, it's so interesting that there are these other sorts of outcomes that are unfolding which may be peripheral to the major event which has brought everyone together but is nonetheless equally important, if not more. So, I wanted to ask you Patrick to finish up our conversation, after all these years of working as an anthropologist in the policy space, what unique contributions can anthropologists have in helping to develop and inform more effective policies – whether they relate to Aboriginal affairs, or whether they more broadly affect general society?

It’s the ability to suspend your preconceptions or your own firmly held beliefs in order to listen and understand where somebody from a fundamentally different cultural orientation is coming from because what they are trying to communicate to you is very important. An anthropological skill that we can bring to our interactions is to focus on that deep listening and encourage others to do the same. Also, I think there's something that attracts all anthropologists to the discipline in the first place, which is just simply a deeply felt appreciation for cultural differences. I think we can try to encourage that among the wider population. Thirdly, but I think more problematically, as I mentioned before, while we can act as interpreters and try to express from our understanding and our own experience of interactions with people of another culture why they're doing what they're doing, and what their aims and aspirations are, and that they need to be valued in their terms, I think we need to be cautious of this because we cannot adopt political struggles that are not our own. But I think that if you do have the experience and insight into a particular issue then you are under an obligation to speak on that topic, some Aboriginal people would disagree with me, but I would say so long as you do it in a respectful way and in a way that acknowledges the authenticity and credibility of other voices, then you should speak and try to persuade.

Photo: Steven Kinnane

Photo: Steven KinnaneInterested to learn more about Patrick’s work? Follow him here.

Listen to Patrick’s recent podcast with Marda Marda man Steve Kinnane entitled ‘Fighting for Aboriginal Self-Determination - Forty Years of Policy Conflict in the Kimberley’ here.

Read the latest book that Patrick and his colleague Kathryn Thorburn have published entitled ‘Voices from the Frontline: Community leaders, government managers and NGO field staff talk about what’s wrong in Aboriginal development and what they are doing to fix it.’

Listen to Patrick’s recent podcast with Marda Marda man Steve Kinnane entitled ‘Fighting for Aboriginal Self-Determination - Forty Years of Policy Conflict in the Kimberley’ here.

Read the latest book that Patrick and his colleague Kathryn Thorburn have published entitled ‘Voices from the Frontline: Community leaders, government managers and NGO field staff talk about what’s wrong in Aboriginal development and what they are doing to fix it.’