Sine Plambech documents global migration and human trafficking

Interviewer: Courtney Boag

Images: Sine Plambech

16 February, 2024

“We are living in a progressively historical moment and we need to reflect on the past to clarify where we have come from and how things have become what they are today. When we meet at this place of understanding and seek to appreciate the relationship between the past and the contemporary, we can see how our diverse lived experiences are entangled together and how they actually mirror and influence each other in interesting ways.”

Sine Plambech

Dr Sine Plambech is an anthropologist, film director, and Senior Researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies. She has been Visiting Professor at Yale University, LSE and Columbia. Sine specialises in the areas of migration, smuggling, trafficking, and the sex industry. She works and films in migrant communities, border areas, red-light districts, and along migrant routes in West Africa, Asia, Europe’s southern border, and Denmark. With the multi-award-winning films, Heartbound and Fra Thailand til Thy, Sine Plambech stepped firmly onto the international documentary film scene. She dedicates her time to research, filmmaking, and social justice movements on the rights of migrants, women, and sex workers.

Firstly, Sine I'd love to know how you became an anthropologist. What's the story?

Why do I research what I do? I think these are still open questions for me.

But I'm beginning to understand more clearly that I have a kinship with the kind of anthropology I'm interested in when it's combined with feminist perspectives and approaches, I think I received these interests from my mother.

I grew up in a feminist and socialist home, where the conversation about solidarity and workers' conditions out in the world was an everyday conversation, something we always spoke about.

It was a feminism that was not out to 'save women from the third world', but instead it was in solidarity with women. In my work, I have been critical of what is called 'white feminism' – where 'whiteness' and Western values are seen as superior, and women's problems and struggles are made universal.

Can you tell us more about 'white feminism' and how it homogenises the diverse experiences of women around the world?

Underneath narratives of ‘rescuing’ or ‘saving’ are these broader narratives of ‘victimisation’, where women who sell sex or migration for their livelihoods are not recognised for their capacity to make choices and to impose those choices on their lives even under constrained situations. Approached from this agentic and intersectional perspective, women migrants are not merely victims, but also decision-makers who, having few opportunities, seek to maneuver through various obstacles in their search to achieve some kind of livelihood and security in their lives.

You have written about how the lines between 'victim' and 'criminal' become blurred with regard to the sex workers that you work with in your research and how there are often 'hierarchical structures' within the sex economy. Can you explain what you mean here?

Because of their sex work and migration, they are the centre of several opposing discussions and assumptions about whether they are victims, vulnerable, coerced, exploited, trafficked versus strong, free and empowered. They are usually somewhere between these extremes. Despite all the times life has attacked them, they are counter-narrators to images of migrant women, sex workers and women from poorer countries as passive victims of coercion, trafficking, violence, men and poverty. They see themselves as rebels, problem solvers and workers, who do not passively put up with poverty, unemployment and a harsh life for themselves, their children and their parents.

Why do I research what I do? I think these are still open questions for me.

But I'm beginning to understand more clearly that I have a kinship with the kind of anthropology I'm interested in when it's combined with feminist perspectives and approaches, I think I received these interests from my mother.

I grew up in a feminist and socialist home, where the conversation about solidarity and workers' conditions out in the world was an everyday conversation, something we always spoke about.

It was a feminism that was not out to 'save women from the third world', but instead it was in solidarity with women. In my work, I have been critical of what is called 'white feminism' – where 'whiteness' and Western values are seen as superior, and women's problems and struggles are made universal.

Can you tell us more about 'white feminism' and how it homogenises the diverse experiences of women around the world?

Underneath narratives of ‘rescuing’ or ‘saving’ are these broader narratives of ‘victimisation’, where women who sell sex or migration for their livelihoods are not recognised for their capacity to make choices and to impose those choices on their lives even under constrained situations. Approached from this agentic and intersectional perspective, women migrants are not merely victims, but also decision-makers who, having few opportunities, seek to maneuver through various obstacles in their search to achieve some kind of livelihood and security in their lives.

You have written about how the lines between 'victim' and 'criminal' become blurred with regard to the sex workers that you work with in your research and how there are often 'hierarchical structures' within the sex economy. Can you explain what you mean here?

Because of their sex work and migration, they are the centre of several opposing discussions and assumptions about whether they are victims, vulnerable, coerced, exploited, trafficked versus strong, free and empowered. They are usually somewhere between these extremes. Despite all the times life has attacked them, they are counter-narrators to images of migrant women, sex workers and women from poorer countries as passive victims of coercion, trafficking, violence, men and poverty. They see themselves as rebels, problem solvers and workers, who do not passively put up with poverty, unemployment and a harsh life for themselves, their children and their parents.

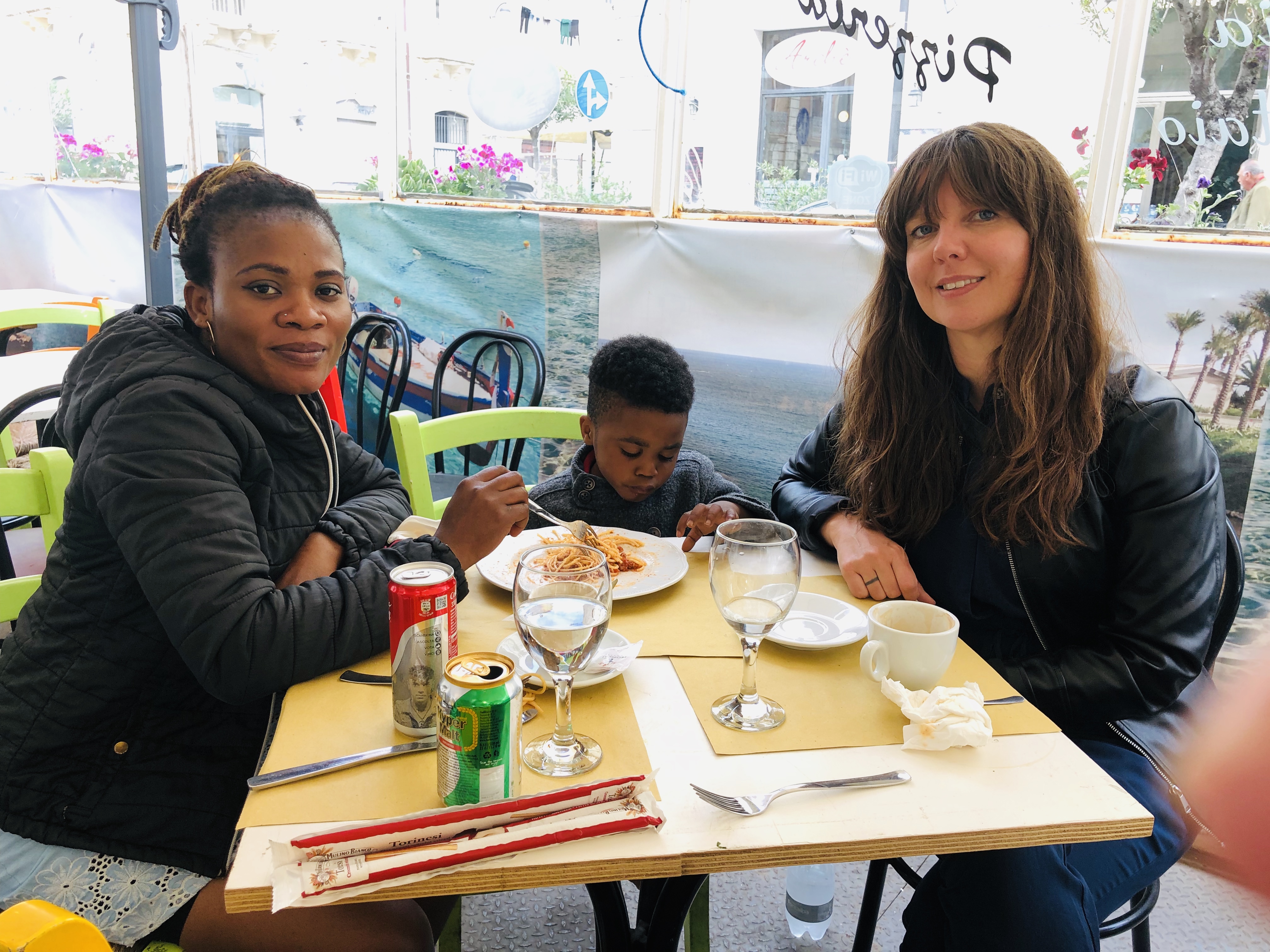

Sine during fieldwork in Thailand

So, let’s talk about your current research. Sine, you explore the movements of undocumented migrant women from and through Africa to Europe and throughout the Mediterranean and seek to understand the role that sex work and human trafficking play in that circular economy. What drew you to these issues?

My notes and my research are a journey in the trail of sex across the globe. But it is also a journey that illustrates the footprints, so to speak, of global capitalism. The sex workers and migrants I work with travelled from their home countries – Thailand and Nigeria – to South Korea, Malaysia, Denmark, Italy, England, Libya and Dubai to work. They selected their destinations according to where there was money to be made and – sometimes – according to where there were more open borders.

They were not governed by what the legislation was for sex work – where it was legal and illegal to buy and sell sex, but instead, where there were opportunities for them. Where there was access. Where money is, comes sex also, as with other goods and services. So in my research, I follow some of these women who travel to new places around the world as things become difficult, expensive and dangerous for them within Europe and because there is money to be made elsewhere.

I have followed the developments that have taken place in the global marketplace of sex sales, especially among women from Thailand and Nigeria. Women from those countries make up two of the largest groups of sex workers in Europe, including Denmark. They typically come from two areas: the Thai women from Isaan in north-eastern Thailand and the Nigerians from Benin City in Edo State. It is perhaps more accurate to say that the women have followed in the footsteps of the men who have followed in the global footsteps of capitalism, and sometimes also in the footsteps of war. The first customers of Pattaya sex tourism in Thailand were white, Western European men and American soldiers on 'rest and recreation' from the war in Vietnam. Since then, soldiers from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have travelled to places throughout Thailand, but especially to Pattaya.

That's a very interesting concept Sine and one I had never really connected the dots on. So, it's interesting to hear you speak about the circular nature of trafficking in this sense – that it follows this very structural process, and as you say, it's a very capitalistic structure directing all this. You have also used film as a medium to communicate your research through documentaries, many of which have been widely acclaimed. I wanted to ask you, what inspired you to begin producing documentaries, and what role do you think film has as a medium for anthropology?

Researchers are increasingly expected to communicate research results in shorter, easy-to-understand and media-friendly formats. But how can researchers adapt to the new reality without oversimplifying complex issues? I think film is one of the methods we can use to do this well.

As anthropologists I think we are very well suited for this – we have very in-depth and nuanced research findings and access and trust from the people we work among. So we get a very close-up understanding of topics that are political, economic, social, cultural and so on and so it's important to tell broader audiences.

Where written research often gives room for context, observations and analyses, films usually have less room to include explicit historical and cultural contexts. That's not to say that movies don't provide context, but they provide a different kind of context. A text is good at providing a theoretical, statistical and historical perspective and is supported by notes and a bibliography. A film can contribute another type of context: everything that goes on in people's immediate environment and in the immediate interaction, which can be difficult to reproduce in writing. Research that is documented on film is thus just as much related to the emotional dynamics that are shown.

Sine during fieldwork

Fieldwork image from Heartbound

Your three films: Heartbound, Becky's Journey and Trafficking are incredibly raw yet immensely illuminating and beautifully shot. The documentaries intimately follow the lives of women who are migrating to new countries for various reasons and via different means. They are a raw depiction of the challenges that women face throughout the entire migration process (before, during and after the transitions). Can you tell me a bit about the process of making these films?

Heartbound is based on my ethnographic research and follows the migration of four women from Thailand who are leaving their impoverished village for Denmark. At first, these stories seem straightforward, Asian women looking for a way out of poverty, but a different, more complex story unfolds. The film is based on my longitudinal study of migration over ten years exploring universal questions of migration, belonging and family. A tale of migration and globalisation set on the intimate stage of marriage. It seeks to show the perspectives and counter-narratives of women migrants.

Heartbound had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, North America's largest film festival and has among multiple prizes been awarded 'Best Film' by the American Anthropological Association.

What inspired you to first pick up the camera and begin using film in your ethnography?

Since 2003 as an anthropologist, I have worked among women migrants, primarily sex work migrants or/and marriage migrants, from and in Thailand and Nigeria who travel to Europe. Theoretically, I primarily find kinship with critical trafficking studies and transnational feminist theory.

Having these theoretical foundations as my point of departure, I became increasingly interested in the collaboration between anthropology and film and the potential of research-based films to produce counter-narratives to dominant stereotypes or representations within a range of themes, particularly countering dominant images of women migrants and sex workers.

As an anthropologist and filmmaker, I have been involved in, co-directed and directed five documentaries on the topics of marriage migration from Thailand to Denmark, sex work migration to Europe, and Thai women in the sex tourism industry in Thailand.

HEARTBOUND Trailer

This film is directed by Janus Metz and Sine Plambech.

This film is directed by Janus Metz and Sine Plambech.

Becky’s Journey

A film directed by Sine Plamech

A film directed by Sine Plamech

What impact do you hope your research can have in the lives of the people you work with and within broader society?

Films often carry a potential for political impact as they usually reach much wider audiences than academic papers. As such they also provide a space for voices within the sex worker rights movements and in migrant communities that might otherwise be muted.

But to fulfil this task, it is necessary for the filmmaker(s) to collaborate with the participants and together show the complex interlinkages between localised and global contexts. Yet, of course, while films have the potential to reform existing representations of human rights issues, there are no quick-fix solutions.

What role do you think anthropology plays in society?

I think we need to have tougher skin. I think we have to go further, be more honest, messier and more courageous in our research and work in solidarity with people. This requires us to let go of the notion that we must be the polished and distanced researcher who simply gazes at 'The Other' and does not put himself or herself at stake. Anthropology was a scientific but also a colonial project, and so the role of the anthropologist in relation to the people they research has also rightly been problematised over history.

But it feels no longer sufficient simply to indicate one's own identity, their position of power and what privileges one has and then just move on with perpetuating our Anthropologist position, because this can really influence the answers we get in interviews with people we work with. We must be willing to test and examine different approaches and put ourselves in more vulnerable positions where we can honestly reflect on the very real ways that we are connected to a historical, but also contemporary, business of colonialism, slavery and exploitation.

We need to be open to fragility and shame as these feelings bring us in touch with our empathy and interpretation of other people's lived experiences. This is the approach I try to take in my current work and what I hope to continue doing in the future. We are living in a progressively historical moment and we need to reflect on the past to clarify where we have come from and how things have become what they are today. When we meet at this place of understanding and seek to appreciate the relationship between the past and the contemporary, we can see how our diverse lived experiences are entangled together and how they actually mirror and influence each other in interesting ways.

Interested to learn more about Sine’s work? Follow her page here.

View the full range of documentary films by Sine via her IMDb profile.

Read some of Sine’s published work via her profile on the Danish Institute for International Studies.

Follow Sine on Instagram via @sineplambechxand via X on @sineplambech

View the full range of documentary films by Sine via her IMDb profile.

Read some of Sine’s published work via her profile on the Danish Institute for International Studies.

Follow Sine on Instagram via @sineplambechxand via X on @sineplambech